An acknowledgment of tradition coupled with a refusal to conform to established conventions makes Analia Saban an artist not easily categorized. Her work flows seamlessly across genre, concept and medium.

A native of Argentina, Saban recalls arriving in California nearly a decade ago. “When I got to UCLA, I was confused because there was all this attention always going to painting. I thought, why is painting so important? Mainly my work became about questioning painting. I am still trying to figure out, why paint?”

With a praxis that originally centered around paint in a literal sense—rather than the results that come from the act of painting—Saban now uses experimental processes, a wide range of materials, and new technology in conjunction with traditional techniques. Her video on MOCAtv follows an artwork transitioning from a painting into something sculpturally different as her laser cutter removes specified areas of the canvas.

An investigative approach has the potential to change one’s trajectory, but alternately it can lead to a frustrating end. For Saban, the failures seem few and far between—she acknowledges that it is a small price to pay for all the research that comes from her studio experiments. She states, “I would much rather keep pushing those limits than make something that will last forever and be perfect. Rauschenberg always said that artworks should have a life and, someday, if it decays, that is okay.”

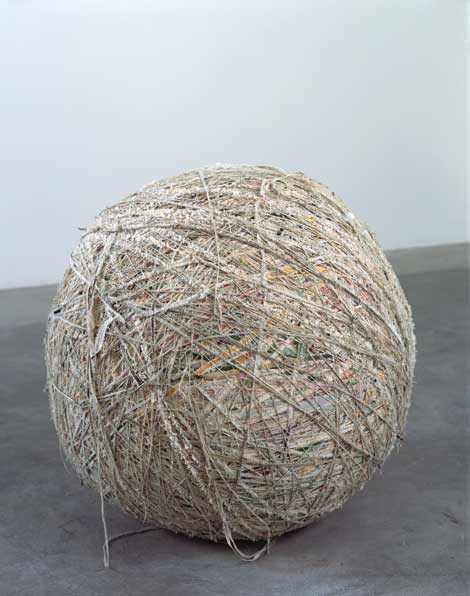

Materiality and its contrived value are at the core of Saban’s artwork; she is an artist fully engaged in an evaluation and dissection of the hierarchy of art processes. An earlier work that she recently exhibited at Marian Goodman Gallery in New York exemplifies both her investigation and critique of the often-overlooked physicality contained within painted canvases. The Painting Ball (48 Abstract, 42 Landscapes, 23 Still Lives, 11 Portraits, 2 Religious, 1 Nude) (2005) consists of 100+ deconstructed pieces of art that Saban obsessively amassed. The criteria for collecting the paintings, whether procured directly from artists, through ads on craigslist, or even from Chinese reproduction factories, Saban explains, was not the beauty or imagery of each work. “It is important to see a painting, this object that we hang on the wall that we have added this value to, is also a knitted piece of material called canvas. Once unravelled, you realize that it is just thread with pigment.”

Saban was recently in two Los Angeles shows; both questioned what it means to be a painter and explored the fringe. “Variations: Conversations in and around Abstract Painting” at LACMA featured striking newly acquired works complemented by pieces from LACMA’s collection. The exhibition embraced the contemporary definition of abstraction, which blurs across painting, sculpture and at times, installation. Saban’s solo show “Is this a painting” at the Armory Center for the Arts in Pasadena probed a famous conversation between Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner asking themselves the same question. Fittingly, not one of Saban’s pieces for the exhibition included paint.

No longer a full-time Angeleno, Saban travels to LA every two weeks to work with her team in a Santa Monica studio, a Baldessari hand-me-down. In a smaller Manhattan studio she works in solitude on drawings, new ideas and photo-related projects. This allows for a nice balance with her more intricate and demanding sculptural works, although it means an epic commute.

Having gallery representation in Los Angeles, New York, Berlin, London and Paris, Analia Saban is a poster child for the global contemporary artist, with a focus on exploration, new ideas and pushing the outer limits of what is possible when combining traditional and experimental ways of thinking about art. Reflecting on her blossoming career Saban states, “I think I have a solid understanding of what it is to be a successful artist in other cities around the world—LA is just by far the best.”