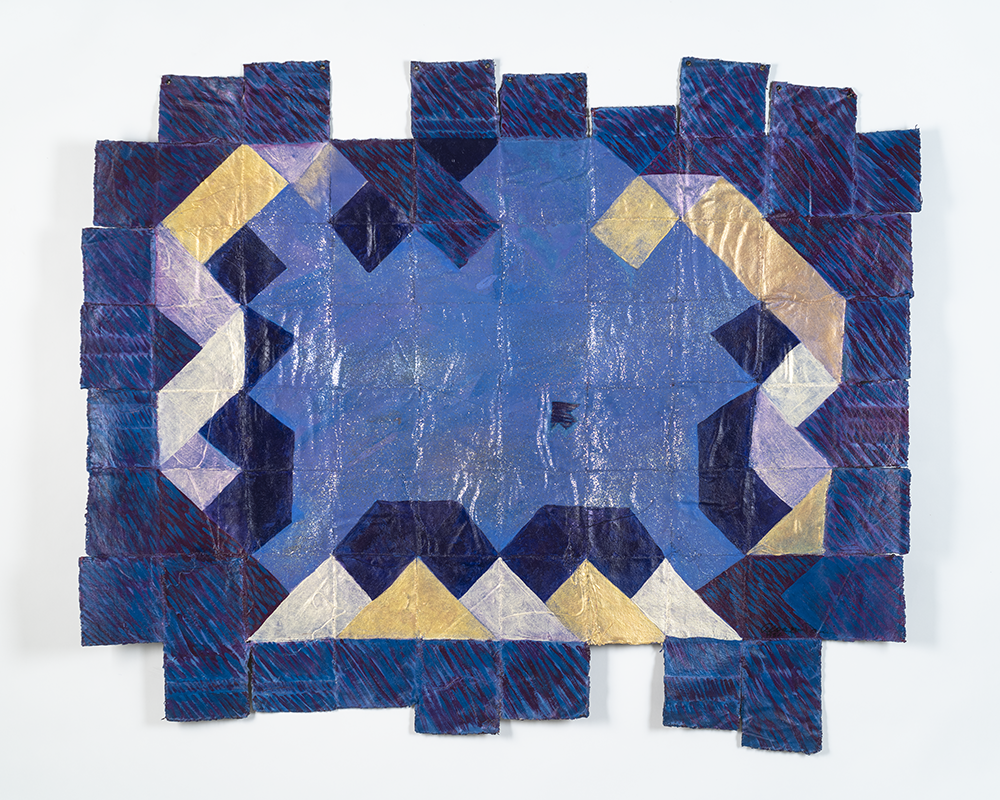

Alonzo Davis’ paintings are breathtaking in their materiality. Using saturated, refractive palettes, and woven paper and canvas to form a layered topography, the works assert their physicality as much, if not more than the imagery. Abstract—but with elements of pictographic language, landscape and quilting to which the title “Blanket Series” refers—Davis’ works are engaged with their 20th-century milieu, the art history that preceded it and, intriguingly, with the current discourse surrounding abstraction.

Davis is in a lively conversation with such art historical figures as Robert Rauschenberg, Paul Klee, Carlos Almaraz, Howard Hodgkin and Joe Ray; but his work also has much to contribute to the present moment. We are in a period in which abstraction has been increasingly cultivating its power of storytelling through expanding its material and gestural fields into more dimensional, personal and even spiritual territory. This includes an understanding of traditional craft as a deep cultural expression, with voices from Gee’s Bend to Sanford Biggers taking up quilting as a practice and a metaphor—which is exactly what Davis is up to in these affecting and unforgettable paintings.

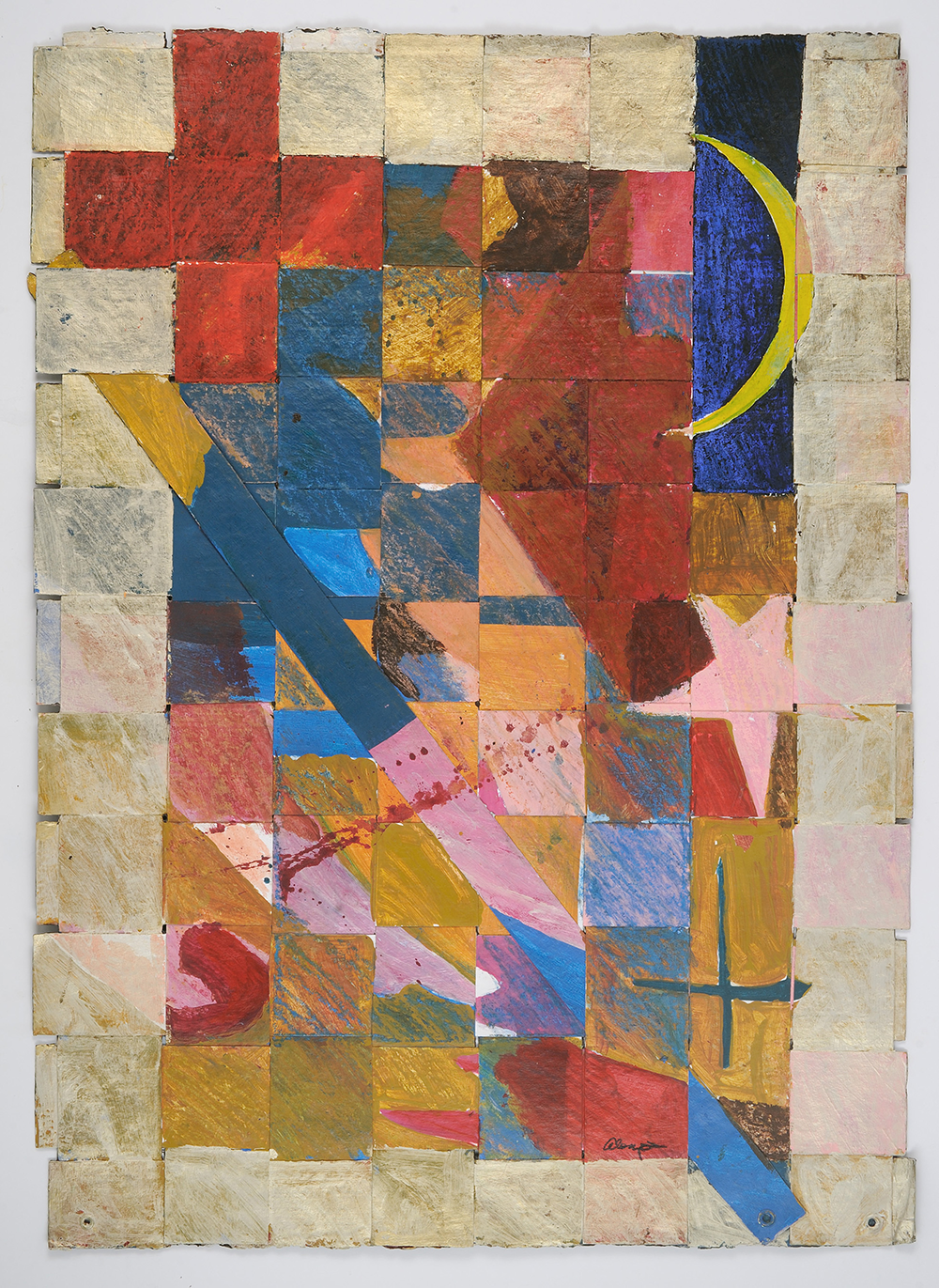

Alonzo Davis, Twilight, 1986. Courtesy of the Artist and parrasch heijnen, Los Angeles

Each brushstroke is as articulated as a stitch, and layered such that the foundation remains visible even under coats of assertive color and thick pigment. Compositions are built in sections, square or shard-like, overlapping and woven in wide strips, or sewn like patchwork. But, because of the generosity of the paint-handling, despite fragmentation, each stiffened unframed work occupies its wall space with the singularity of a modern painting and the gravitas of a regal tapestry. Celebration with Melon (1986) displays a skirt of fringe that enhances the textile effect, but the glow of its pink-forward personality forces a conversation on paint. Copper Flash (1989) also explores such possibilities, buried in a deep pink field of granite split by a lightning strike, perhaps being held together by gold at its broken seam like kintsugi.

Flotation Reflection (1996) presents like an elaborate picture window looking out across the sea to the horizon. Its receding pictorial depths are a sweet spatial bend that is echoed elsewhere in the exhibition. It finds a curious counterpart in Twilight (1986) whose massive central window is a celestial glitter bomb with a small arrow pointing skyward. The arrow is a recurring motif, of the kind most heavily expressed in the urban musicality of Crescent Moon Over Memphis (1993), the most scenic of the works, and the most literal as to hiding a story in its codes.