One of my favorite paintings is a portrait of myself at the age of five or so, composed by my father. Along with my siblings’ pictures and beyond the sentimentality, these portraits have become distinctive family emblems and historical markers, wrought at a time of optimism and possibility. That singular ability to capture transitory moments and ephemeral character is the essence of portraiture, the subject perpetually reanimated. Portraiture raises notions of conditional identity and, even when not flattering or mimetically precise, is curiously alluring. It has been a fixture in non-Western art for millennia, along with the belief that a person’s physiognomy provides insights into their persona—imagined or factual. Our fascination with countenances permeates culture, and our acquiescent relationship to them via painting, photography or selfies, is ubiquitous. Contemporary artists have taken on the technique anew—although engaging with “portraiture” does not necessarily align them as “portraitists.”

Jamie Vasta, an Oakland-based artist with a BA from Tufts Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and an MFA from California College of the Arts, San Francisco, operates on such a continuum—her work straddles notions of representation and more recently, landscape or “environmental portraiture.” She has a particular interest in reframing LGBTQIA+ narratives, posing her circle of friends and collaborators in often foreboding historical tableaux. The clincher is that all of her works are created utilizing glitter and glue—pedestrian materials that utterly transform both context and allusion. Composed on flat panels with painstaking subtlety, it’s a physically onerous creative process.

Glitter has a particularly American history, invented in the 1930s by Henry Ruschmann, but the artistic use of shimmering substances can be found in antiquity. The stuff is often associated with queer culture, drag queens and rockers alike—“glitter bombing” is frequently employed as a political tactic. Use of lustrous materials by contemporary artists isn’t particularly new, Andy Warhol’s Diamond Dust Shoes (1980) is embellished with a shimmering glass-based powder and emerged at a cultural moment of extreme disco and concomitant bacchanalia. Notorious bad boy Damien Hirst went a step further with his fully diamond-encrusted skull, For the Love of God (2007) and ancillary diamond-dusted prints. Artist Ebony G. Patterson takes a more considered approach—her lush works employ glitter, but it’s a bit of a subterfuge: “Beneath all of the layers, beneath the shine, beneath the patterns beneath the embellishment sits an uneasy question. The question is whether or not you choose to look for this,” she states.

Vasta works in a similar vein; she adroitly compels the viewer to consider the nature of the human condition: desire, joy, sexuality and death all play roles in her multiple mise en scènes.

Jamie Vasta, Narcissus, 1603, 2010. Private Collection. Courtesy of the artist.

“The Hunt,” an early suite of paintings, depicts female hunters celebrating in what is often controversial territory, but the series doesn’t purport to be a visual treatise, quite the contrary. The amiable portrait, Virginia (2007) depicts a young, proud girl hunter, hoisting a formidable rifle while imbibing on a juice carton. The materialism of glitter and the familiarity of the imagery both honor and assuage a provocative, sociological juxtaposition: This is America.

The “After Caravaggio” series is a contemporary reframing of Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio’s historic paintings. The original Narcissus, depicted in the Mannerist style, illustrates a young boy in 16th-century garb, languorously gazing onto his reflected image, the outcome ultimately tragic. With Narcissus, 1603 (2010), Vasta envisions an alternative narrative and inserts a tattooed T-shirt–clad male gazing into a cocaine-laden baroque mirror, rendered entirely with glitter. The resulting picture is beguiling and decadently glamorous, its calculation pushed into the 21st century with the consequences in question.

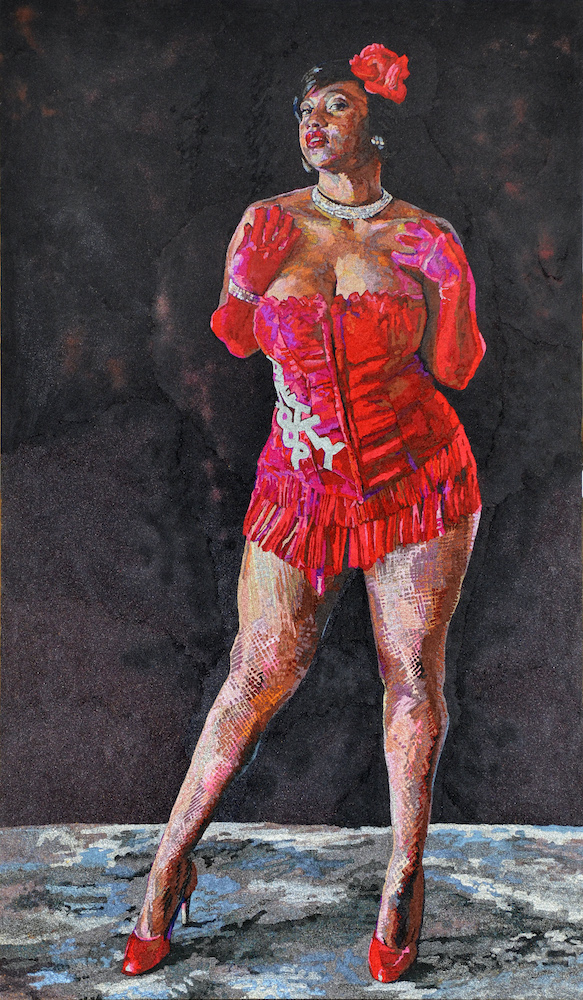

Don’t haul on the rope don’t (2009) from the “Sea Shanties” series presents an altogether darker narrative, the forces of nature subsuming a young man drowning in a pall of darkness, glitter confounding his plight. “This series was decidedly vague and foreboding,” says Vasta. Even so, it’s impossible not to be mesmerized by the pictures; light plays an outsized role in their hypnotic appearance. With Elyse Elaine (2012), a work in the “Burlesque” series, a formidable Black woman proudly sashays as a radiant performer, her confidence, desire and focus beyond reproach, glitter propelling her portrait into superstar status. As the artist says, “I was interested in the ways that both burlesque and drag play with camp femininity, and in what’s similar and different about how each do so, and how that might relate to the connotations of glitter as a material. I wanted to give the portraits some art-historical gravitas, so the models and I utilized a lot of poses drawn from John Singer Sargent’s society portraits.”

Jamie Vasta, Elyse Elaine, 2012. Courtesy of the artist.

The artist’s most recent work has taken a bit of a turn from her staged portraits; the 2020 series “Fire” posits destruction as metaphor for cultural implosions—glimmering conflagrations of a collapsed world. “The fires seem more personally relevant now that I’ve been living in California for almost 20 years, and then when COVID happened the fire paintings suddenly became very much about the pandemic to me.”

Vasta deftly resurrects splendor from moments often bleak or inconclusive; her considerable forte is imparting an astute sense of erudite and seductive spectacle. In her hands, the medium is only part of the message.