Working in a continuous exegesis of an overarching project, pursuing branching pathways to their conclusions then returning to the center and setting off again, Alison O’Daniel transforms elusive ideas and ambiguous experiences into concrete objects—still and moving images, time-and sound-based installations, and discursive narratives of extreme specificity. In recent years, that hub has been her feature film The Tuba Thieves—an interpretive documentary using conceptual and somatic strategies to tell the story of a bizarre string of music room robberies at a public school.

At the core of O’Daniel’s practice is her deeply considered status as a Deaf/Hard of Hearing person and the unique perspective on the world which that affords. Her expansive work touches on musicality, politics, civil engineering, physics, anatomy, science, language and landscape. In The Ownership of Onomatopoeia, the vector she revisits is a scene in which the character Awet recalls being so shaken by the explosion of a sonic boom that he badly cut his hand on a saw blade. But the show moves beyond its nested premises into a macro view of how social, economic and environmental structures coalesce to exclude Deaf experience. Along the way, the scene’s imagery and dialog generate materially and optically charged mixed-media sculptures for wall, floor and mobile, a mural-scale photomontage, audio interventions, and text-based sculptures culled from its dialog.

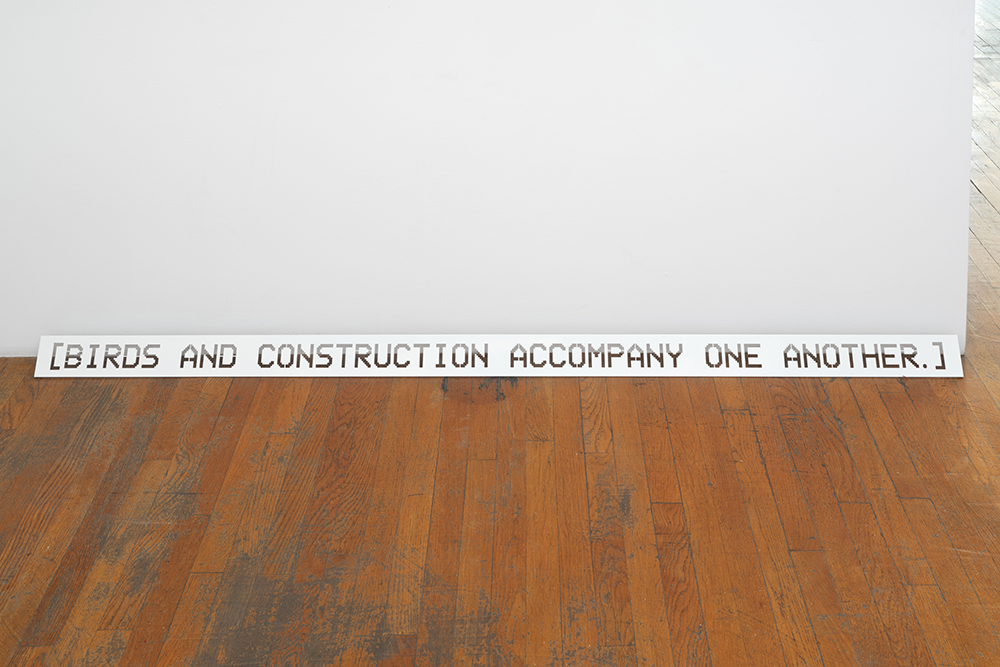

Alison O’Daniel, Sound Segregations – Birds and Construction, 2022. Courtesy Commonwealth & Council.

The entrance is activated by the fire-engine red Neighbor Relations (powder-coated steel & aluminum, 2022)—a giant suspended wind chime whose charms are stylizations of Awet’s hand. Nearby is an oversized rug made of wool, nylon and, crucially, sound-swallowing carpet, Awet’s (Non)dominant Hand (2022). The hand motif repeats along with a red-and-white pattern based on the injury-inflicting saws—a rust-patinated collection of which hang from the ceiling in “Threat to Language.” The photos show hundreds of sonic booms—something we think of as a sound yet has a visible manifestation.

Energy converters in the walls vibrate and hum, directly invoking the noises roaring off the LAX flight paths—over neighborhoods with no power to resist or ameliorate the low rumble, which can be felt as vibrations as well as heard as disruptions. Around the edges of the room, about a dozen white caption sculptures whose industrial font cut-out words comprise the Sound Segregations—Birds and Construction (powder-coated steel, 2022) say things like “We open the windows because we don’t have air conditioning /The planes come every two minutes, so we wait to talk /Santa Ana winds cover us in soot and sound.” In its approximation of a domestic environment, the elements reference engaging, amped-up versions of ordinary decor, but O’Daniel turns it all inside out to not only communicate the nuances of events, but to generate a direct experience for the viewer—and break some sound barriers of her own.