After living through the angst-laden whirlwind that was 2020, I can’t imagine a better show to see than “Alice Neel: People Come First” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Neel’s dual focus on ordinary, often invisible people and social justice issues resonates powerfully and offers a kind of corrective symmetry to Trump, COVID-19, and the violence against people of color epitomized by George Floyd’s murder. The world has caught up with Neel, not just stylistically, but also politically.

A true bohemian, Neel (1900–1984) operated outside the art establishment for most of her career. She left Greenwich Village and the New York art scene for Spanish Harlem in 1938. She never divorced the husband she married in 1925, taking lovers and having sons by two of them. A nonconformist herself, she was naturally drawn to others, painting pictures of artists, gay couples, underground performers and political activists.

Neel’s nonconformity extended to her erotic watercolors and her approach to the nude. Her many portraits of heavily pregnant women showcase this fundamental aspect of life that had previously been taboo. In 1972, she turned her gaze on poet and art critic John Perreault, depicting him in full-frontal naked glory. Continuing her explorations, she painted Cindy Nemser and Chuck (1975) seated somewhat tentatively in the all together on a formal Empire sofa, and, with extreme lack of vanity, her own 80-year-old self, naked as a jaybird.

Self‑Portrait, 1980, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., ©The Estate of Alice Neel.

Like a caricaturist she exaggerated people’s features; her goal was not humor, but highlighting her subject’s essence. This approach extended beyond her sitters’ visages to include other body parts, clothing and furniture, overemphasizing, for effect, their individual characteristics.

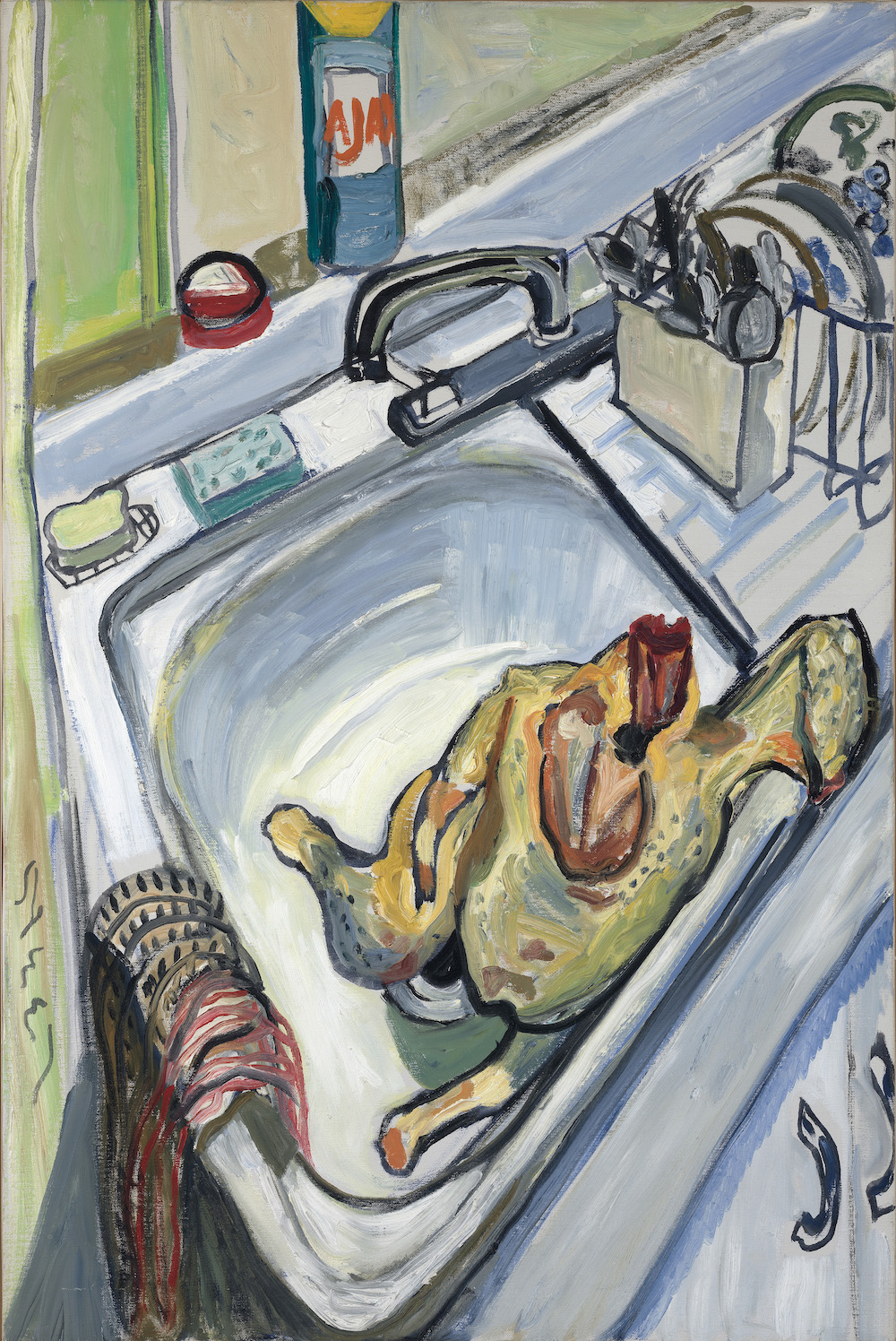

Neel invested nearly the same intensity into objects and pieces of furniture. Thanksgiving (1965), a portrait of her kitchen sink, boasts a lively assortment of soap, sponge, rags and Ajax joined by a turkey carcass slumped in a corner. In Cut Glass with Fruit (1952), a fluted dish and compote come alive with a crazy quilt of crosshatches, slashes and shapes that somehow coalesce to produce the exact quality of those kinds of dishes. Neel couldn’t afford a studio and painting in her apartment often included pieces of furniture like the blue-and-white striped armchair that appears in her nude self-portrait, Black Draftee (James Hunter) (1965) Benny and Mary Ellen Andrews (1972) and other works.

Thanksgiving, 1965, The Brand Family Collection © The Estate of Alice Neel

Neel uses pattern to great effect, inserting a striped shirt, an Indian handblocked bedspread, or a plaid bathrobe. The motifs and colors are often quite bold, but she doesn’t overdo it, using one, or perhaps two, and keeps it fresh and unpredictable by sometimes not using any pattern at all.

For Neel, who felt very strongly that man was the measure of all things, abstract art was anathema. Yet again and again in her paintings, the formal elements—color, composition and gesture—have a stand-alone weight and importance that transcends the representational aspects.

Trading off the heavy black line that surrounds the subjects in her earlier works for electric blue was an inspired adaptation that breathes vitality into the work. Neel also began to leave sections of the paintings unfinished. This helped direct attention to the more detailed sections, namely the face and eyes, but it also imbued the paintings with modernity. In the case of Black Draftee (James Hunter), she uses it serendipitously for dramatic effect. The recently drafted Hunter never returned for his subsequent sittings. It was the height of the Vietnam War and Neel embraced the unfinished aspect of the painting as a powerful metaphor for Hunter’s presumed unfinished life.

The Spanish Family, 1943, © The Estate of Alice Neel

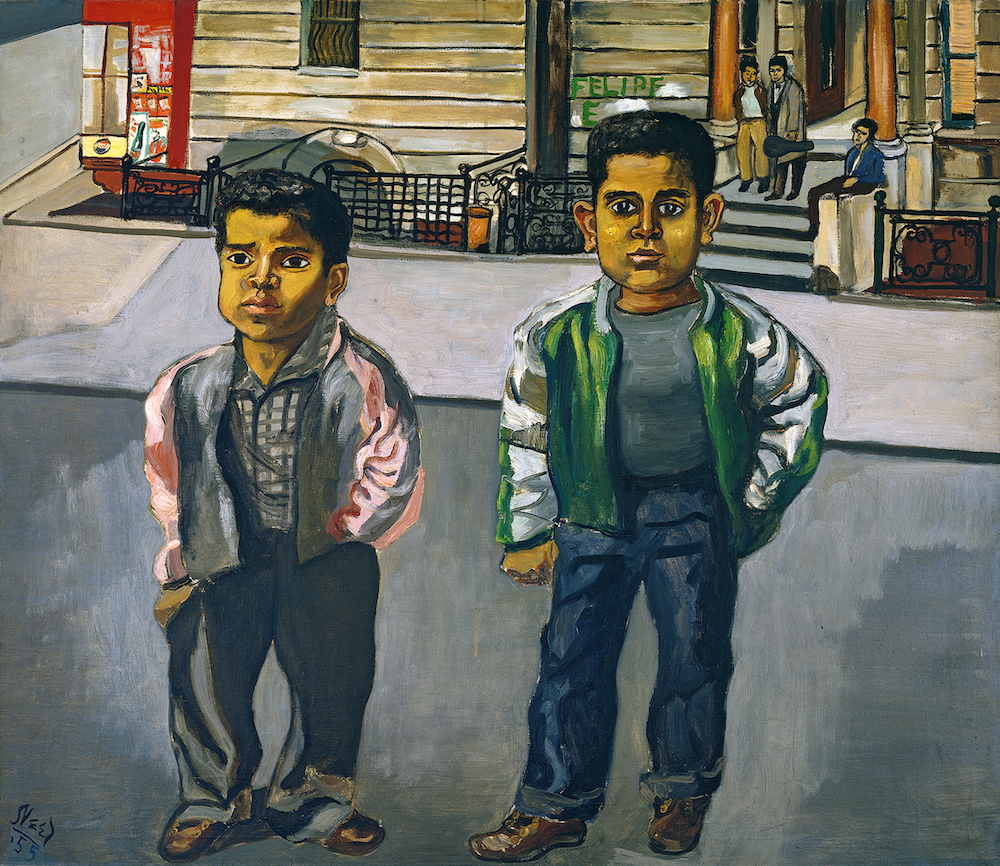

Neel treated her youngest sitters with the same gravitas she did their elders, understanding that children are individuals, and childhood is not always the easy, carefree existence it’s purported to be. Solemn and soulful, Two Girls Spanish Harlem (1959) and The Black Boys (1967) painted before and just after the Civil Rights Act, present these small humans with great empathy. Their expressions suggest they already know the tough road that faces them ahead.

Richard (1963) and Hartley (1966) are powerful psychological studies of the artist’s sons. Direct and confrontational, the boys stare out at the viewer. Richard is warily buttoned up, Hartley more relaxed. Neel uses a similar palette in both—mauve, burnt sienna and ochre to describe the merest suggestion of a background. The brushwork used to convey the clothes is extraordinary, particularly the dynamic folds of Hartley’s rumpled khakis. His arms, stretched over his head, are long and lean with the slight bulge of his left bicep capturing the exact quality of a young man’s tender musculature.

Hartley, 1966, (detail) National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Gift of Arthur M. Bullowa, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National Gallery of Art ©The Estate of Alice Neel

Moving through the galleries, you see Neel’s evolution as she worked through the dour portraits of the ’40s, distinguished by that heavy black line and somber colors. She had a lot of personal burdens—a dead child, a lost child, a couple of abusive relationships, poverty and lack of professional recognition coupled with fierce ambition—and yet, we see this remarkable transformation occurring from obdurate gloom to a kind of joy. It’s not that she felt the weight of things any less—she remained politically engaged all her life—but it’s as if she attained a kind of acceptance or, at least, shifted her focus from the conditions surrounding the subjects she painted to the people themselves, finding bliss in representing them just as they were.

And how they were! One’s heart warms to this messy jumble of humanity that at once seems so immediate and also from a simpler, more authentic time before the avaricious 1980s, the AIDS epidemic, 9/11, Citizens United and social media. While working in opposition to the many injustices and alienating forces in America, Neel captures what the world, and New York in particular, looked like. Viewing it through post-2020 lenses and following months of isolation, Neel’s world—where people come first—seems ineffably appealing.