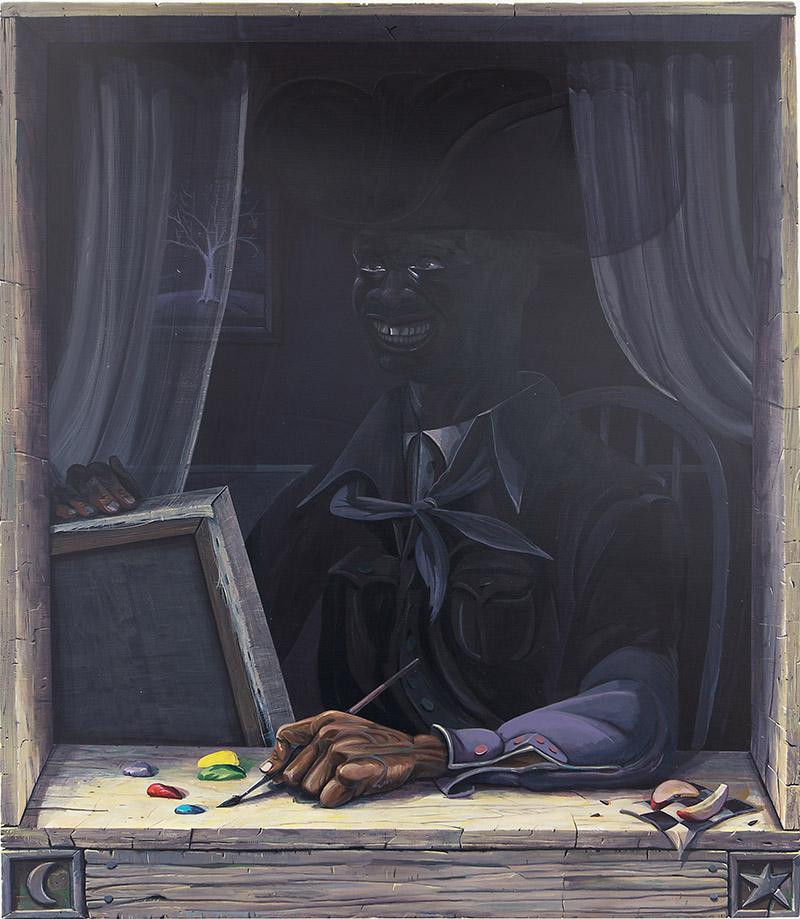

Alexander Harrison’s aptly named exhibition “Midnight Everywhere,” is an exploration of the moods, tones and colors that the night brings. The paintings in the exhibition form a cohesive collection and tell the story of a solitary artist living in an old wooden house in the middle of nowhere, surrounded by apple trees and rolling hills with only the stars and flowers to keep him company. The focal painting, Portrait of an artist in the penumbra of the moon, in hopes for a brighter future (all works 2021), gives insight into who the main character in this story is—a Black cowboy with a toothy grin gazing out the window, painting the midnight sky.

In many ways this “artist character” gives the collection a meta quality. Although the paintings were created by Harrison, one could suspend their disbelief and instead infer that the paintings were in fact painted by this mysterious cowboy. The still life paintings of watermelons, apples and flowers are what he would paint after a long day, and show snapshots from his life, giving the impression that this cowboy could have simply looked around his environment and painted what he saw in his surroundings. The consistent color palette is effective: the deep blues and purples give the impression of moonlight spreading over each scene. It’s easy to visualize the quiet, secluded cabin in which all of this introspection and recording took place, and to fill in the blanks of who this artist is (the one in the painting, not Harrison himself). The cohesive story is echoed by repeating themes in the paintings, such as checkerboard cloth, or watermelon seeds from a windowsill in Midnight Picnic, which also make an appearance in The Moon.

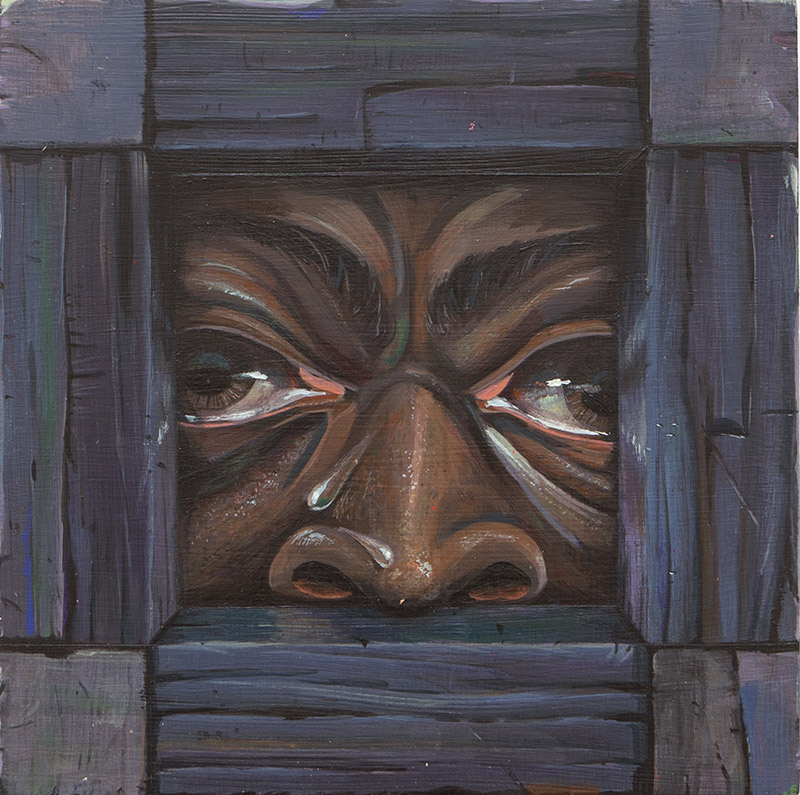

Alexander Harrison, Counting Sheep, 2021. Courtesy Various Small Fires.

All of this storytelling elevates the show to a metaphysical level, and changes the context of the figurative paintings that contain subject matter that could be seen as elementary—how many art students paint fruit for their first assignment? This does have its downfall, however, as the pieces are stronger as a collection and some may not hold up as well as solo efforts. This is a show that is greater than the sum of its parts.

Harrison’s interest in storytelling goes beyond the paintings’ content, and into his painting techniques as well. Many of the paintings have a trompe-l’œil effect, in which Harrison has painted frames around the composition. This strategy suggests a vantage point from within the painting, further immersing the viewer in the world he has created. The windows also tell another story, as sweeping landscapes and a sense of stillness are juxtaposed by imagery of one being trapped. In Counting Sheep, a face peers out of a tiny opening, and in Why’d I have to Go n’ Dream so Big? the windowpane suggests a jail cell. This obvious longing that the artist in the paintings has is palpable, and from the solitary Light of Mine in the room of its own, it appears that the fire is still burning.