The 40-Year Funeral

By Pat Williams

There are very few people alive today that can remember a time when conceptual art was considered to be unusual. To most of us it came as a given, buried in among our earliest memories of museum-going. You enter with a parent or two and are presented with an enigma—not of form (it is often something you’ve seen earlier that day)—but of curation. Why this particular pile and why is it housed within these exalted white walls? Why must I be on my best behavior to look at something that resembles the bed I am repeatedly told I must make or the overflow of the kitchen trash I was told to take out? You find out, over years, by degrees and osmosis, that this is one kind of art: They just put things there. Why? If you remain curious about art until college, someone will tell you.

“Joseph Beuys: In Defense of Nature” functions less as an art exhibit than as a historical exhibition of a time when this kind of art was novel. The curators tried to fill the first-floor galleries with a large and wide-ranging sample of Beuys’ sculptures, multiples, images and ephemera. 1974’s Green Violin (Grüne Geige) stands out—by virtue of being one of the few pieces that isn’t brown.

Despite being an outspoken advocate for animals, plants, the downtrodden and the overlooked, there was one benighted minority for whom Beuys had no sympathy: the viewer.

A video of Beuys’ best performance, How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare (1965)—known to most students via the disturbing still-photograph of Beuys’ holding the titular animal in his arms with his own head creepily covered in honey and gold leaf—proves that the photo oversells it. We see an at-first-curious crowd shift in boredom after realizing there’s only so much conversation to be had with this morbid prop. In two hours, Beuys produced one compelling image—whereas any halfway-decent horror film contains at least three.

All this is blasphemy, of course. To his defenders (a group that historically has included the entire contemporary art world), Beuys has long been a secular saint of Teutonic eco-seriousness. Though the first room’s wall text thankfully debunks Beuys’ oft-repeated lie that his obsession with felt and fat began after he was rescued from a fighter crash by tribesmen and kept warm with this earth-toned pair of primordial substances, Beuys’ greatest aesthetic achievement remains in having endowed everything he touched with such a Holocausty aura that rejecting him seems not only uninformed but an unforgivable breach of decorum.

In funeral parlor fashion, pieces by Beuys are shown side-by-side with ephemera from his life—magazine covers, photos of the great man swimming, etc. This results in no visual or cognitive dissonance as it is all indistinguishable. His sculptures were only ever artifacts, in the original and religious sense of the word—souvenirs whose value derives solely from contact with a wholly conjectured divine.

Just as one’s reaction to the little-league jersey of a child taken too soon or a dead author’s battered copy of Strunk & White is taken as a measure of your sensitivity, to be moved by the mute testimony of Beuys’ felt suit or bottle of rainwater is to testify not necessarily that you knew the man, but that you are wised-up on all the context and symbolism tucked away behind the vulgarity of what is merely on display.

Joseph Beuys, Pala, 1983. The Broad Art Foundation. Photo: Joshua White. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bon

If the argument for the actual objects’ desultory irrelevance seems philistine, know that others have made it before—most prominently, the late Joseph Beuys. In a 1969 interview for Artforum with Willoughby Sharp, he says it over and over in a variety of ways:

Sharp: Has your teaching at the Düsseldorf Art Academy for the last eight years been an important function for you?

Beuys: It’s my most important function. To be a teacher is my greatest work of art. The rest is the waste product, a demonstration.

Beuys: Objects aren’t very important for me anymore. I want to get to the origin of matter, to the thought behind it.

Sharp: Nauman’s work shares a similar sensibility.

Beuys: Yes, but I find it hard to define because I don’t know Nauman’s inner intentions. I place great importance on inner intentions.

Beuys: Yes, I keep on refusing to exhibit until someone like Schmela convinces me that it’s an absolute necessity.

Sharp: Is this a reaction against materialism in general, or is it due to the fact that there are more demands on you today than there were in 1967?

Beuys: Both. People are becoming more demanding. They are getting sharper. I was glad when Ströher took everything away. Things have to be some place, and I have never wanted to collect my own things. I like empty walls best.

Say what you want about the pretension of LA restaurants, but they don’t give you food made by chefs who like empty stomachs best.

Beuys asks us to judge his work on something other than itself? Let us do just that.

Beuys’ “inner intentions” are impeccable. He was a tireless advocate of democracy, a campaigner for student’s rights; his protéges include Lothar Baumgarten, Anselm Kiefer, Jörg Immendorff, and Blinky Palermo; he was one of the founding members of the German Green Party; he gave funny interviews.

All this is not bad for someone whose first recorded political act was volunteering for the Hitler Youth. While Benjamin Buchloh suspected him of fascist tendencies and said “The esthetic conservatism of Beuys is logically complemented by his politically retrograde, not to say, reactionary, attitudes.” I am not here to cancel him—canceling Beuys would be giving in to a myth he deeply believed in—that the art is nothing but an extension of the man. He was the opposite of a cancelable genius—here is an artist who was often right, but never good.

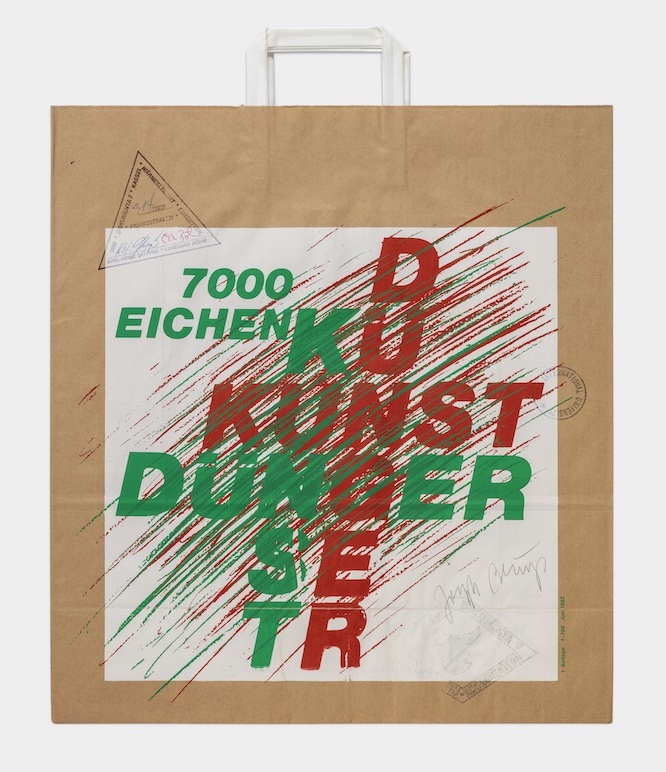

Anyone tempted to take Beuys’ rhetoric of art as “shamanism,” “spirituality,” “healing” and “social sculpture” on its own terms rather than just as how a hippie of a certain age and level of education talks would do well to examine the large room devoted to Beuys’ last major work, 7000 Oaks (1982). This massive project began when Beuys decided the German city of Kassel should have more trees. Rather than simply doing what George Clooney or Bono might have done and donate money, sell work, or use his public profile to raise capital for the undertaking and then go back to making art, Beuys donated money, sold work and used his public profile to raise money for the project while announcing it was the art. To remind everyone that the planted trees were art and not something that someone just did, he made sure that a nondescript stone pillar no more or less visually captivating than every other postcard or bundle of felt in the exhibition was installed next to each oak.

It is difficult to argue with the painter I know who opined: “7000 Oaks is the most disgusting and conservative piece of art ever made. Oxygen, shade, sure. But as art—the whole reason humans invented art was so they could look at something besides one more fucking tree.” While at the time many might have argued that tree-planting-as-art was a radical gesture, it is impossible to overstate how little creative risk or experiment is involved in bringing trees to a country which consists of one-third forest. Works like this do not so much bring Beuys’ dictum that “Everyone is an artist” into doubt as beg the question of why anyone would want to be.

Beuys did have an answer to that question—he claimed that he was a provocateur, eager to spark discussion, and like all blue-chip artists, he has.

On YouTube, the briefly amusing Felt TV—where Beuys, among other things, punches a television—has garnered 8000 views and 5 comments, the highest-rated of which is, “I farted”.

On a Beuys documentary with 130,000 views, the top-rated comment reads, “Just came to see how his name is pronounced. Thx”.

The second-highest rated comment says, “An absolute legend”, just below which someone asked, three years ago: “Why?”.

The comment remains unanswered.

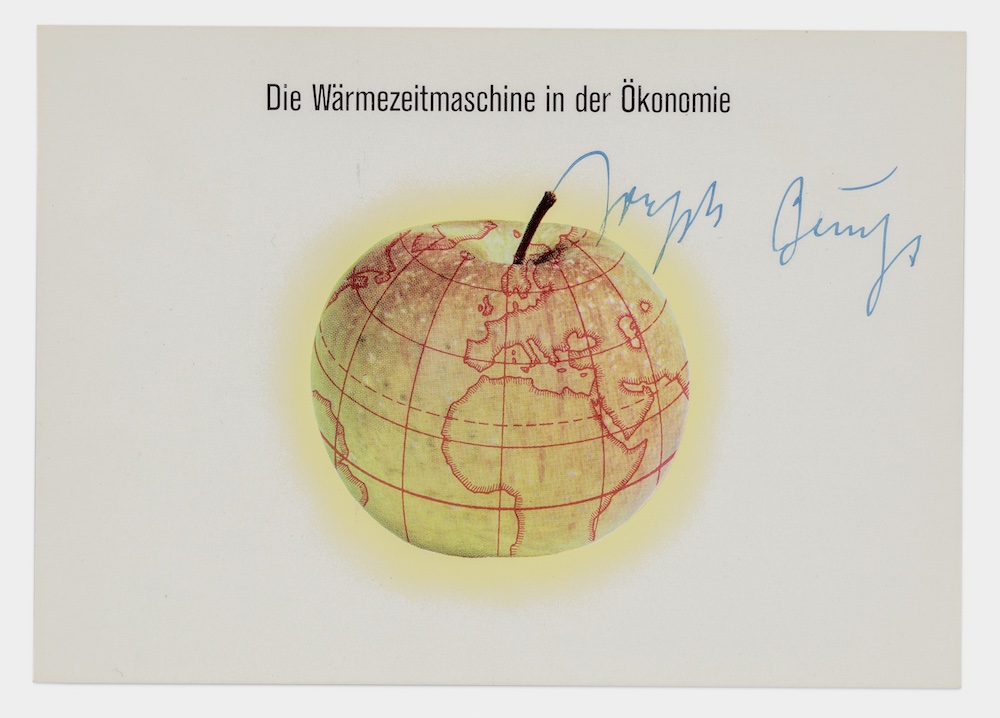

Joseph Beuys, Die Wärmezeitmaschine, 1975. The Broad Art Museum. Photo: Joshua White. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Angst and Alchemy

By Daniela Soberman

My love affair with Joseph Beuys’ work began at the Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin, while I wandered through galleries brimming with German contemporary art angst. At the end of a series of rooms filled with far-too-serious art in a limited color palette (mostly gray), I entered an enormous chamber that offered relief in an unexpected form: A sculptural tribute to fat. It was, to be precise, beef tallow, and the piece on display addressed tallow’s use as an historic wound salve. The place was filled with overgrown sculptures made out of the yellow, dirtied substance—some six feet high, and placed on the floor in seemingly no particular order. It looked as if a family of giants had thrown a party and offered up a room-sized cheese plate. I immediately developed a full-blown and unshakeable crush.

The tallow sculptures I encountered are a part of Joseph Beuys’ Unschlitt/Tallow (1977), a series of works the artist made by filling a wedge-shaped 10-meter-long replica of a pedestrian underpass with the thick viscous material, allowing it to harden, then cutting it out into six sections. Beuys presented the work as “social sculpture”, a phrase coined by Beuys that refers to works that celebrate common humanity, which he believed would be a valid vehicle to bring about revolutionary change.

These slabs of tallow, created from an ingredient used to care for others in the form of salve, feed, or fuel—transformed into bloated cracking cakes—offer a study in dichotomies and a response to just how uncaring the human species can be. It wasn’t that the sculptures were good in the classical sense. There was nothing particularly special about their shape. Nor were they especially avant-garde—sculpture made from unconventional materials was nothing new, even at the time Beuys made these works. What captivated me was the choice to present the monumental chunks of smudged, healing tallow en masse, creating a lunacy-in-object that recontextualized the mundane as a fine art statement full of existential crisis. I felt very much as if someone had reached into the invisible spaces that surround us all and brought back a semisolid slice of a connected world operating on a scale far larger than I was used to.

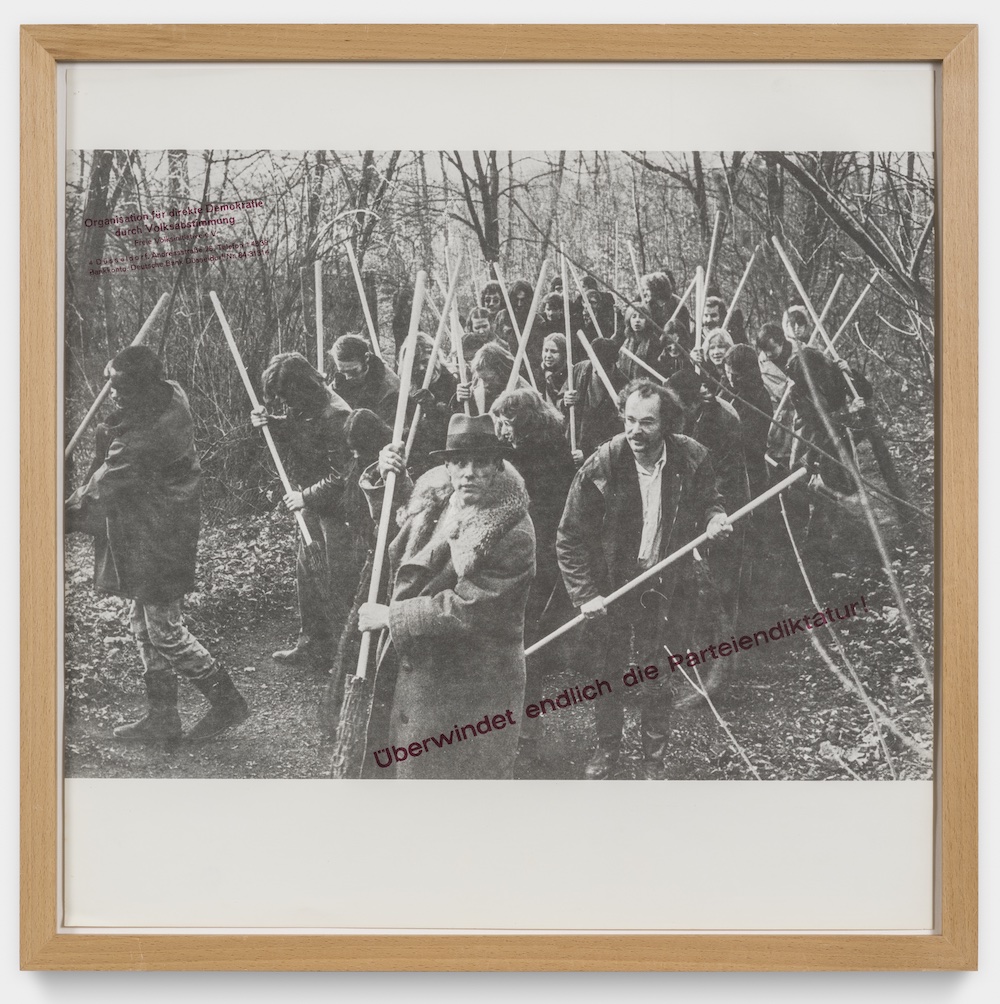

Joseph Beuys, Rettet den Wald, 1972. The Broad Art Foundation. Photo: Joshua White. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

This month I’ve had a chance to revisit Beuys work in person and re-examine what it is that makes his contribution so compelling to me. “In Defense of Nature,” on view at The Broad through March 23, 2025, contains over 400 of Beuys’ social sculptures and multiples (editions of objects meant to be sold or given away) while thoroughly explicating the godfather of modern conceptualism’s theory of social alchemy.

Upon entering the exhibition, one is presented with three of Beuys’ felt suit multiples, modeled after his own suit—concrete-gray, nondescript, stark, scratchy-looking—displayed in a row on the wall. These multiples comment on the relationship between the human figure and the working environments that constrain and define our bodies. The suits, hanging above so many casually and fashionably dressed Angelenos, provokes a simple, but oft-ignored question: What is my role here? What is the role of the artist? Especially as the empty suits unavoidably now refer to the absence of Beuys, a modern shaman no longer with us.

The exhibition soon transitions into an archeological presentation of a variety of deeply human artifacts: Beuys’ personal manifestos, tools and letters, all neatly displayed in plexiglass cases. In the context of Beuys’ struggle to bring the West out of the trauma of World War II and into a sense of peaceful alignment, each object asks more questions than there is time to answer. Observed through the Beuysian lens, every instance of the quotidian becomes what Harold Rosenberg calls an “anxious object”—a fulcrum where essential social adjustments might be made.

Many pieces invite interaction in a more overt and literal fashion: 1968’s Intuition is a simple box in blond wood containing a penciled request that the owner fill it with observations about themself. As so often with Beuys, the very minimalism of the objects suggest a universe of invisible relations which require our attention, no matter how minor. The photographs of Beuys’ Bog Action (1971)—a dance-like improvisation which saw the artist moving, in his trademark hat and pouched vest, through water and reeds in imitation of the threatened wildlife—show the artist bringing attention to environmental issues through ephemeral interactions that bear the quality of practical magic.

A fascinating presentation of mail-art pieces dramatizes the basic act of communication in the form of battered old envelopes and postcards, highlighting the ephemeral and often damaged quality of human interaction. Pointedly, several are wholly symbolic—made of felt and wood—suggesting hidden hierarchies of what we can and cannot share.

Works less central to Beuys’ core thesis included a video piece showing him fronting an 80s Euro-synth band, highlighting his own unique brand of weirdness in a way that feels more like a window into the artist’s need for attention than anything else. Similarly disjointed were several primitivist red-pigmented pieces that felt as if they were created out of commercial necessity during a time when primitivism and cave paintings were gaining attention.

Overall, however, “In Defense of Nature” presents Beuys’ animated thesis clearly and intact. Contact with Beuys conjures a vision of an Eco-social web ever-reacting to the energies we invest in it, and a dense universe of symbol—personal and public—that deepens our understanding of the whole long after we leave the museum.