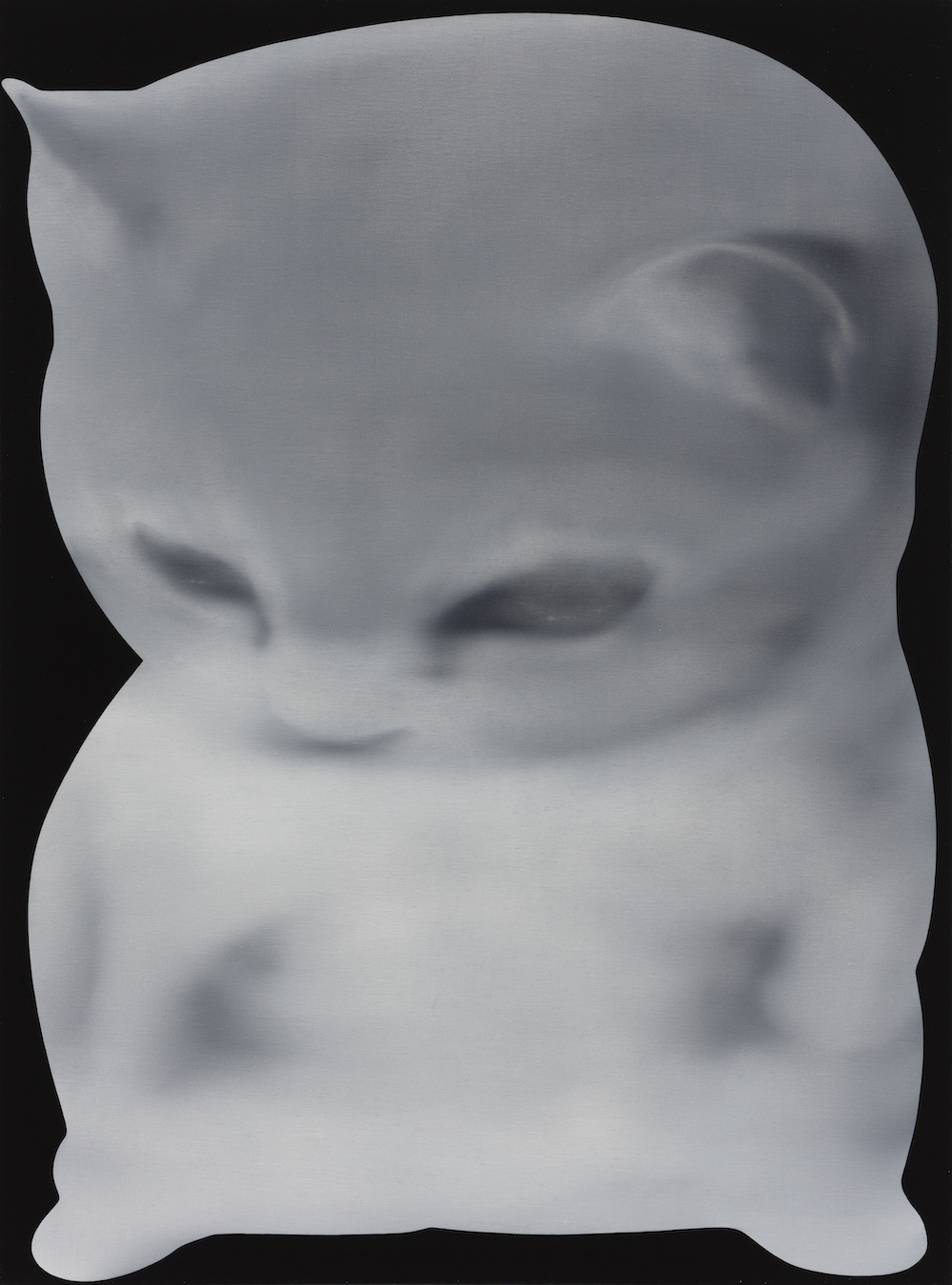

Jingze Du’s exhibition “True Colors” features the most well-executed oils in recent memory and all of them are of cute animals. The animals are mostly uninflected white, and their cuteness is eerie and synthetic. The painting itself is restricted to points of defining darkness like ink drops in fields of snow—typically two eyes (or one when the animal is in profile) and the dark vertices of a mammalian muzzle are rendered with paint pushed deep into the canvas and then teased across until no brush marks remain visible. Only the tracks of the black paint’s footprint across the underlying canvas are left to provide a silkily photorealist gradient into the surrounding plenitude of raw white, extending outwards until a simple outline against a flat dark background shapes the whole into a creature.

For what they are, these paintings are perfect. The only remaining question for a critic is whether they lack ambition. Ancient Asian standards of beauty seem relevant when discussing any artist who starkly isolates and spotlights their touch as a tool for rendering in black and white. When Tang-era scholar and calligrapher Chang Yen-Yüan wrote “…the thing must be complete in the mind even though the manner of the pictorial rendering does not seem to be complete, otherwise no work of art will result, ” he was articulating the central principle of a Chinese art-critical tradition that, for the next thousand years, would inveigh against over- rendering and simple formal completion in favor of capturing the essence of a subject.

Jingze Du, The Death of Marat, 2024. Courtesy of the artist and Steve Turner, Los Angeles.

Du’s canvases capture not so much the essence of his subjects as the essence of our feelings about them—with their feckless vulnerability caged inside toy-like outer selves. The distortions of the figure bring digital filters to mind but the eyes still penetrate, unsettle, invite sympathy, and suggest a strange neonatal wisdom. What is remarkable is how few elements of oil painting are required to work this magic.

I hope the second room of the exhibition, further back, does not indicate a lack of confidence in the relevance of small, uncanny paintings of mutant pets. Here, Du provides much larger interpretations of famous European paintings in a drippier and more aggressive style that could be almost anyone’s. I don’t begrudge a rare talent the exercise of rendering five-foot tall sketchbook pages, but I didn’t need to see these to appreciate the seriousness of his intentions. After all, as early as the ninth century, Han-tzū addressed the question of the relative difficulty of subjects by saying “Dogs and horses are difficult, ghosts are easier; dogs and horses have been seen by everybody, but ghosts are quite effusive and strange.” Du’s paintings manage to merge each beast with its strange, effusive ghost.