Nam June Paik, the “father of video art” and the man who coined the phrase “the electronic superhighway,” weaves humor, Buddhism, technology, music and sex. Paik was born in 1932 in Japanese-occupied Korea. Tutored in piano and composition, he attended college at the University of Tokyo. He moved to Munich, Germany, in 1956 to study musicology and connect with the experimental music scene, attending lectures at the Darmstadt International Summer Courses for New Music given by John Cage, whose conceptual and revolutionary way of looking at composing and performing would alter the course of his life.

Cage, renowned for his avant-garde compositions like 4’33”, scored silence, became a role model for Paik, who along with Alison Knowles, La Monte Young, George Maciunas and others formed Fluxus, an international collective of musicians, artists, poets and performers with a Dada-inflected sense of anarchy. When Paik assaulted him, cutting off his necktie, in the audience at Etude for Pianoforte (1961) in Cologne, Germany, Cage took it in stride. He did however, allow as how “he’d think twice before attending another performance by Nam June Paik.”

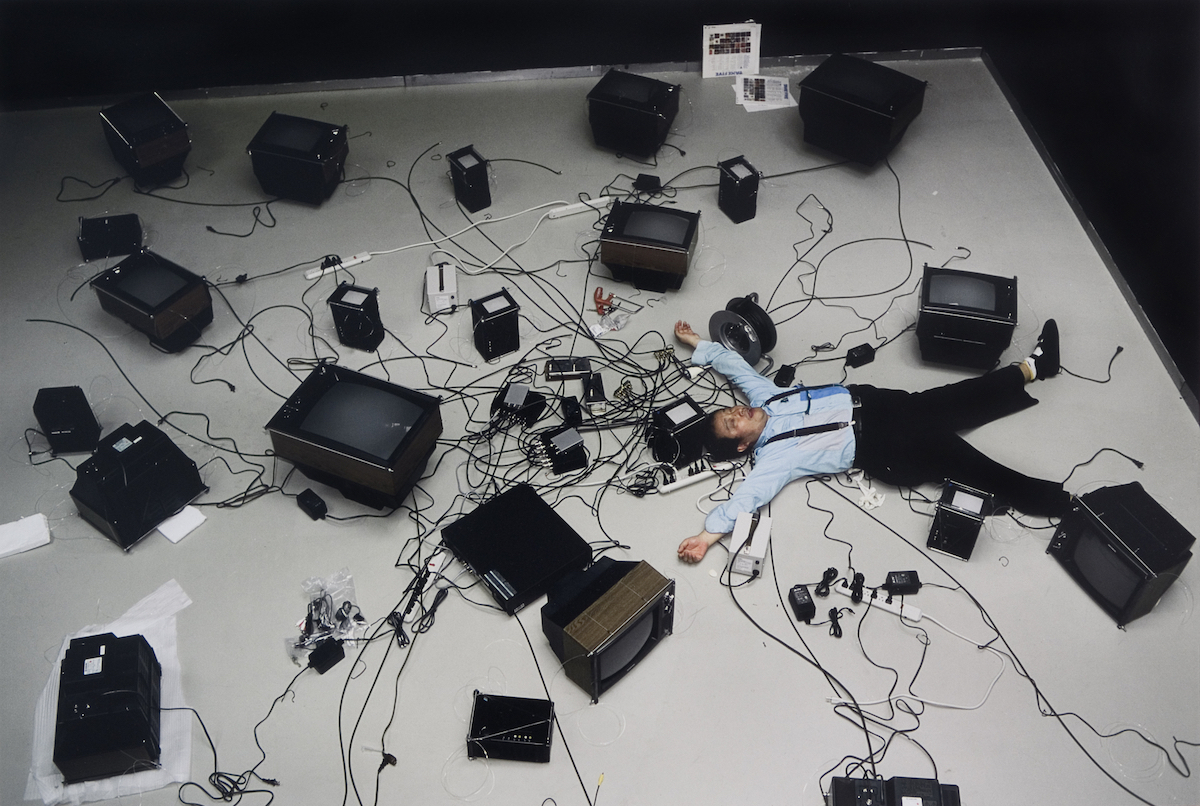

Timm Rautert, Nam June Paik lying among televisions, Zürich, 1991; © Timm Rautert

The sprawling “Nam June Paik: A Retrospective,” a joint project of Tate Modern and San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, will be presented at five venues. Paik, who studied Japanese, German, English and French in addition to his native Korean, epitomizes the multi-cultural artist, embracing a transnational identity that also left him always as a bit of an outsider.

Originale, an avant-garde event first organized by composer Karlheinz Stockhausen in Cologne, Germany, in 1961, featured Paik pouring flour and water over his head, throwing beans at audience, and executing some slow-motion gestures. Entering the exhibition, we pass a larger-than-life video of Paik’s Hand and Face (1961) concealing his face with both hands, then separating them as he strokes forehead and chin. Eyes half-closed, he seems in an otherworldly or meditative state. A TV displays The Button Happening (1965), recreating a sequence of jacket buttoning/unbuttoning, flickering in and out of a field of static, that conveys a barely sublimated sexual tension.

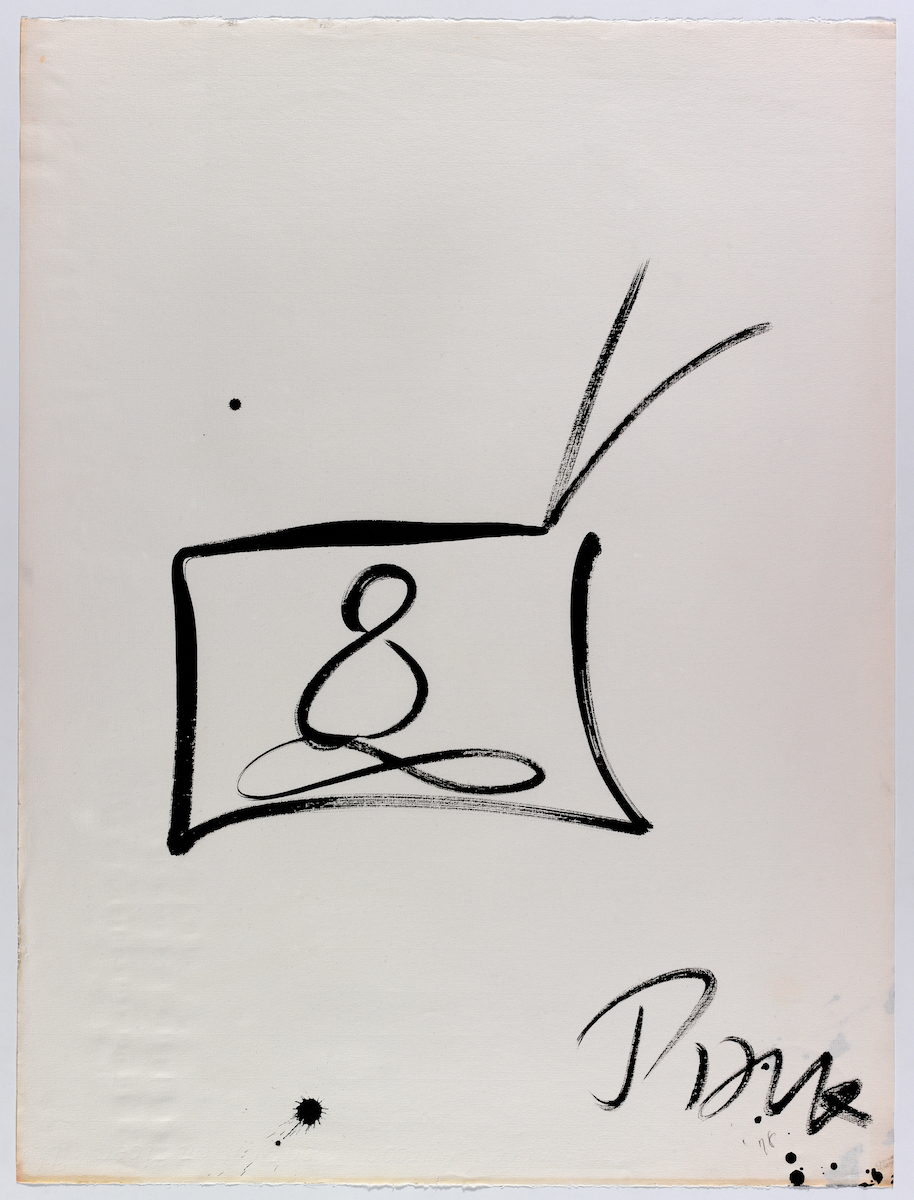

Nam June Paik, Untitled (TV Buddha), 1978; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, gift of the Hakuta family; © Estate of Nam June Paik; photo: Don Ross

Many of Paik’s works relate to Zen Buddhism either directly or by inference. Although raised in Korea and Japan, where Buddhism was a part of the fabric of everyday life, his interest was not sparked until he learned of Cage’s enthusiasm for the practice. Paik’s iconic TV Buddha (1974) explores the intersection of technology and spirituality. A closed-circuit TV camera films an antique Buddha statue contemplating its own image on the screen opposite. As with much of his work, the playfully ironic content is balanced by an underlying sense of serious intention.

Paik collaborated with Shuya Abe on the Paik/Abe Video Synthesizer (1969-72) and manipulated video and TV monitors were at the heart of his practice from then on. TV Garden (1974) packs a large gallery with living plants interspersed with medium-sized TVs, all playing the same synchronized video feed, Global Groove (1973). With a vibe a bit like dipping into someone else’s acid trip, the soothing presence of the plants mellows out a mixture of rock music, interviews and exotic dance routines.

4. Nam June Paik, TV Garden, 1974–77/2002 (installation view, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam); Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf; © Estate of Nam June Paik; photo: Peter Tijhuis

Collaboration is at the heart of much of Paik’s work, a practice that meshes nicely with his inclinations toward Buddhist thought. In 1964 he moved to New York, met Julliard-trained cellist Charlotte Moorman, and the pair jointly conspired to unite classical music and sex—feeling this was a rich vein of untapped potential. Paik composed scores for Moorman to appear topless, bottomless, and fully nude in Opera Sextronique (1967)—all while playing the cello—until the appearance of the NYPD disrupted the proceedings. This sparked the artist’s creation of an imaginative TV Bra for Living Sculpture (1969). Paik also goes bare for an intimate moment where the two intertwine front to front as she plays him like a cello, Human Cello (1967).

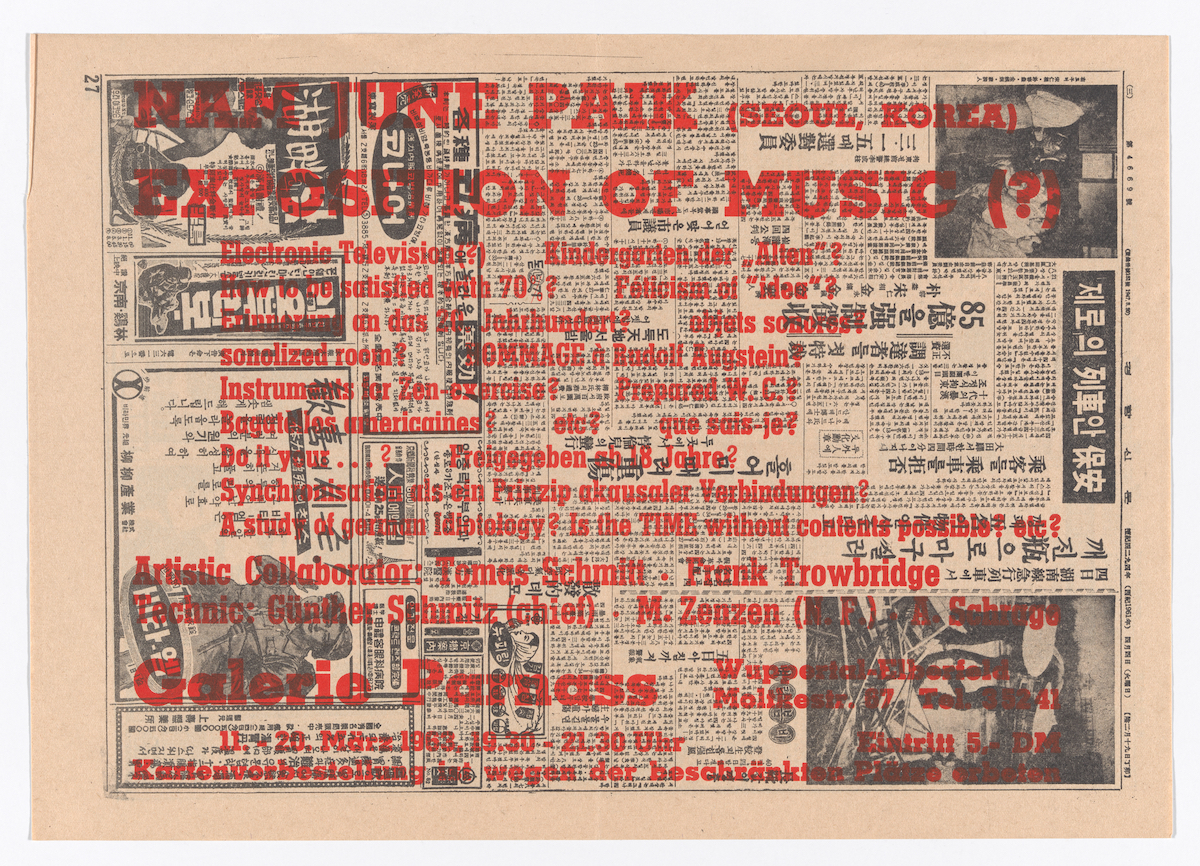

Nam June Paik, Exposition of Music – Electronic Television, 1963; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, gift of the Hakuta family; © Estate of Nam June Paik; photo: Don Ross

Joseph Beuys made an impromptu appearance at Paik’s Exposition of Music-Electronic Television (1963) in Wuppertal, Germany. An upturned piano, part of the interactive sculpture, was destroyed by “the ever-serious and funny man, Beuys,” who chopped it to bits with an ax. Paik liked his addition to the event, and the two, both profoundly affected by the aftermath of war, later shared several notable performance collaborations, including Coyote III (1984) in Tokyo. Paik played the Moonlight Sonata, while Beuys contributed vocal improvisations. With shared interest in the Tartars, Beuys’ spinning the legend of his rescue by a band who wrapped him in felt and fat, and Paik envisioning himself as a modern-day incarnation of a nomadic Mongol horseman, they connected on a unique wavelength.

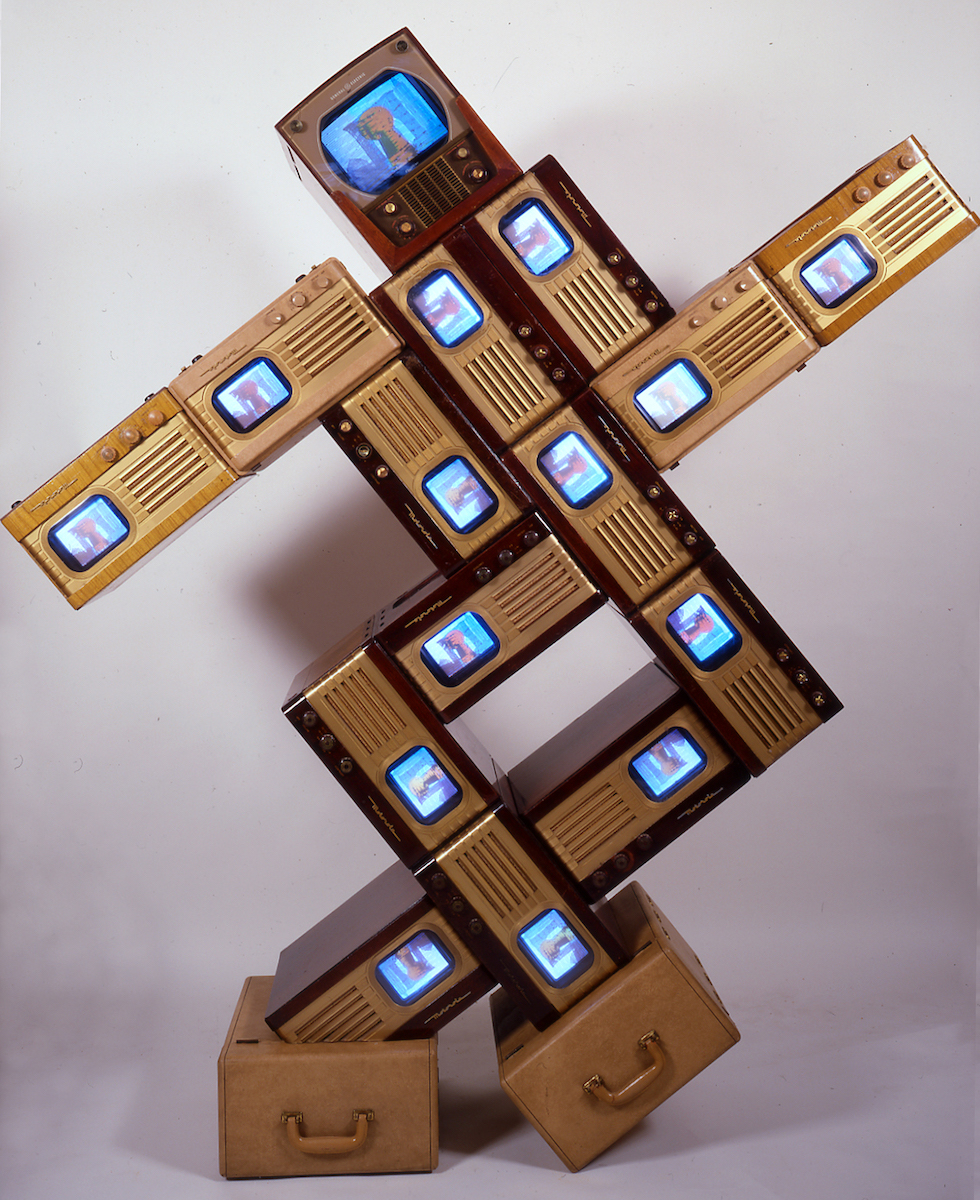

Nam June Paik, Merce / Digital, 1988; collection Roselyne Chroman Swig, San Francisco; © Estate of Nam June Paik

Dance legend Merce Cunnigngham, known for his partnership with John Cage and collaborations with Warhol and Duchamp, also worked with Paik. Videos of Cunningham dancing are exploited to good advantage in a variety of works, including the figurative video assemblage, Merce/Digital (1988).

The climax of the show is Paik’s immersive Sistine Chapel (1993-3019) for which he co-won the Golden Lion for the German Pavilion at Venice Biennale in 1993. Forty projectors cover walls and ceiling with images. Dick Cavett, African dancers, David Bowie, Joseph Beuys and Lou Reed are among the subjects in a remarkable, dizzying video montage.

Paik, who passed in 2006, both anticipated and helped shape our contemporary image and video-driven world. His ability to shape-shift and thrive, and to create this groundbreaking work, is a testament to his resilience and inner vision.

Nam June Paik: A Retrospective

SFMOMA

May 8–October 3, 2021