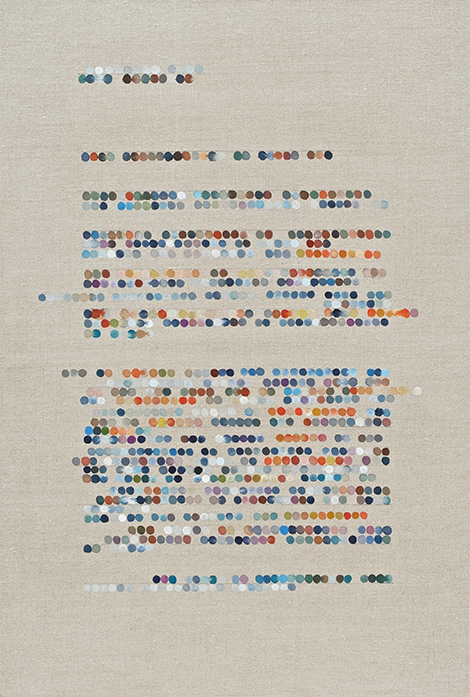

Harkening to the grace of bygone days when those who wished to communicate with one another would do so by putting pen to paper, East Bay-based artist Gail Tarantino’s “Hand Written” draws content from letters written by the artist to astronomers, naturalists and scientists whose discoveries captured her imagination. These missives were then encoded into a system of colored dots, which the artist then composed into a series of poetic works in acrylic ink on linen and paper.

Geometry and patterning are at the heart of these works, the rectangular format of the paper or canvas housing arrangements of small, irregular circles carefully laid out along light lines ruled with pencil. Some of these employ a very restricted palette, such as tints and hues of blue, while others offer a full range of colors, in muted tones. As a system of dots that in a sense codify language, the works also evoke the structure of braille; it may come as no surprise that Tarantino created an earlier body of work in which she translated words to braille, inspired by a conversation between sighted and blind siblings.

With much text-based art, the challenge is often to discover the relationship between word and image. Here one is spared, or deprived, of that task, as there is no direct code by which one could even attempt to decipher content—Tarantino electing for this to remain a mystery.

Numerical Blue-Dear Horace (all works 2015) adds the device of a large circle, approximately 12 inches in diameter, inscribed with pencil slightly above the center of the vertically-oriented rectangle. Stray arcs along the edges suggest trial and error; like many small but significant indications of the mark of the human hand, these engage us in the work in an intimate way. Hues of cobalt blue, phthalo, ultramarine and Prussian are appropriate for a work inspired by Horace-Bénédicte de Saussure and Alexander von Humbolt, the inventors of the cyanometer, a device for measuring the blueness of the sky. From Dim to Bright-Henrietta, rather oddly displayed lying on its back in the gallery window, commemorates the work of astronomer Henrietta Leavitt who, at Harvard Observatory around the turn of the 20th century discovered more than 2,400 variable stars of fluctuating intensity.

Damien Hirst’s ubiquitous spot paintings, strewn across the globe a few years back, may spring to mind when viewing these, as they share a vocabulary of shape and format, yet where Hirst’s dots are often aggressive, punchy and ironic in tone, Tarantino’s are meditative, with subtly nuanced hues and a sensitive application of paint that retains the feel of language, and an inner logic resonating beyond the formal. Her painterly schematic evokes the pulsing pace of reading, with objects scaled to and created by the human body. When language and writing become subject to the vicissitudes of monitor calibration or the viewer’s font selection, the long-standing dialogue between thought and lexical expression loses the magic of the mark, the fragile construct of “handwriting.”