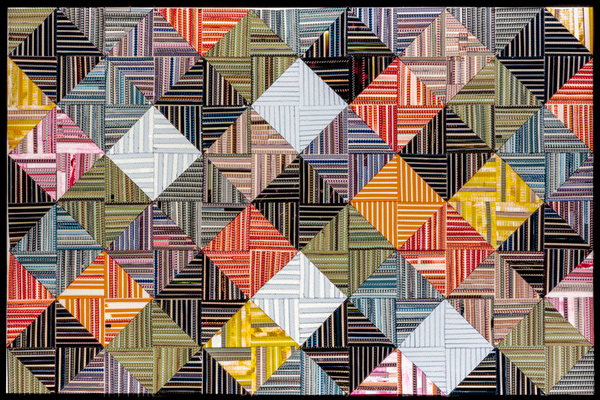

Shoshana Wayne Gallery: : Sabrina Gschwandtner

Sabrina Gschwandtner’s second solo exhibition at Shoshana Wayne Gallery continues her exploration into intricate quilting motifs, expanding on her already complex imagery with the addition of deaccessioned celluloid film strips of female hands hard at work—sewing,...

EDITOR’S LETTER

Dear Reader, “Write what you know”: this famous advice from fellow Missourian Mark Twain has always resonated with me. I apply it to my writing and I relied on it when I used to make art. The quote was delivered by many a professor and mentor in my past. It made...

The Netherlands

Holland has an illustrious past and rich history in art, from golden age painters Rembrandt and Vermeer through modernist legends van Gogh, Mondrian and the de Stijl group, Cobra Dutch artists and expatriate Willem de Kooning, to enigmatic Conceptualist Bas Jan Ader,...

Conceptual Museum: Cesar Cornejo

Cesar Cornejo sees artists as outsiders. They confront things that other people won’t—or can’t—see, the Peruvian-born artist told me in an interview in May, three days after the opening of “Building As Ever,” OCMA’s 2017 California-Pacific Triennial. His site-specific...

South of the Border Down Tijuana Way

Tijuana’s most famous contribution to art is the painting of zonkeys: combining donkeys with zebras so the pale Equus would stand out in black-and-white photographs. This is a paraphrased version of what I’m told when I mention I’m heading to Baja for cultural...

Off the Beaten Path in Barcelona

I landed in Barcelona a little sweaty, slightly hung over, and very much lost. Much to my surprise, the discount tickets I purchased for $350 round-trip included three meals, unlimited snacks, and all-you-can-drink beverages (including alcohol). By the end of the...

Living Larger: Lauren Greenfield

In the earliest days of his unlikely, unfortunate campaign for president, billionaire Donald Trump declared in 2015: “Sadly, the American dream is dead,” adding special emphasis on the last word, delivering the bad news like a judge slamming down a gavel. As in many...

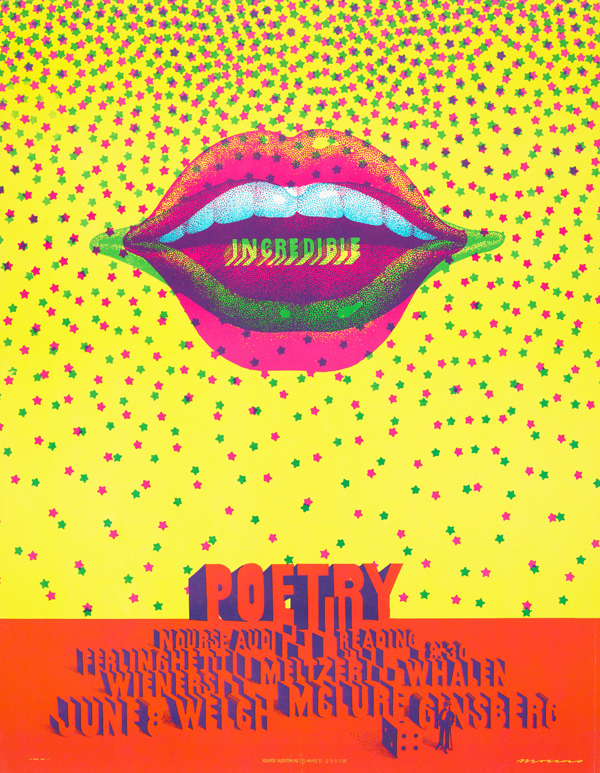

Summer of Love Redux

When I moved to San Francisco to begin college nearly a decade ago, the refrain from Scott McKenzie’s 1967 hippie anthem “San Francisco” rang through my ears, beckoning me to the city by the bay with dreams of “flowers in my hair,” but I quickly learned that much had...

Reykjavík in LA

The Reykjavík Festival at Walt Disney Concert Hall presents an opportunity to experience a site-specific installation by Icelandic artist Hrafnhildur Arnardóttir and a film by fellow Icelander Xárene Eskandar. The Festival brings up a larger question of cultural...

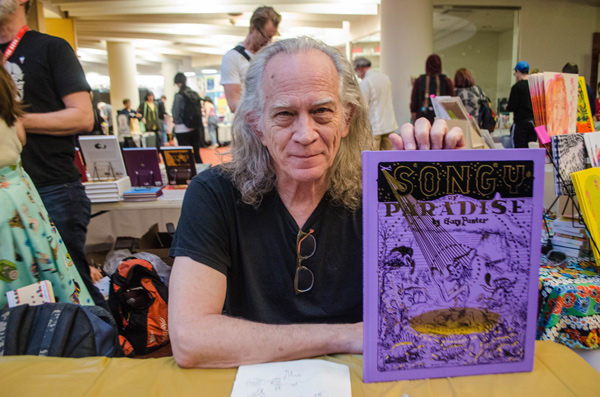

UNDER THE RADAR: Gary Panter

Gary Panter wears many hats—visionary punk cartoonist, Emmy-award winning designer for Pee-Wee’s Playhouse, psychedelic lightshow revivalist, cutting-edge graphic designer, experimental musician, candlestick maker. Having dazzled the comic art world with his elaborate...

2017 California-Pacific Triennial

“Building As Ever,” the 2017 California-Pacific Triennial at the Orange County Museum of Art, investigates the economic, political and social forces that affect the built environment. Themes of gentrification and dislocation, meditations about home and displacement,...

Guest Lecture: Lynda Burdick

Lynda Burdick is Artillery’s staff photographer. On her frequent visits to art openings, she often encounters dogs as well as gallerygoers. Rosamund Felsen of the eponymous gallery has been quoted as saying that dogs are usually better behaved than the children who...

ART BRIEF

Sometimes legislation in Sacramento is rushed through with unintended consequences, an unfortunate example being a newly expanded law posing problems for art dealers. This 2016 amendment to California Civil Code Section 1739.7 was intended to broaden a law that...

BUNKER VISION

Life happens fast. Yesterday’s dystopian fiction is today’s reality. American history now includes a woman in the 21st century being arrested and found guilty by a jury for laughing at somebody. Most places that have an awareness of despots also have some pearls of...

ASK BABS

I Love A Man in a Uniform Dear Babs, Why is it that with all the focus on hip, cutting-edge contemporary art displayed in modern museums and galleries, the security guards dress like they are working at the May Company in the ’70s? The women dress like men and the...

FILM: Manifesto

The film Manifesto speaks in the voice of the 20th century, when manifestos meant something—a time when the latest artist or art movement stormed the Bastille of conformity, declaring the one true doctrine—theirs, naturally—and the rest of us sat up and paid...

RECONNOITER

Elena Shtromberg is Associate Professor of Art History at the University of Utah. She is co-curator (with Glenn Phillips, curator and head of modern and contemporary collections at the Getty Research Institute) for the PST LA/LA exhibition of “Video Art In Latin...