Your cart is currently empty!

Month: February 2016

-

That’s Entertainment: Alex Israel and Bret Easton Ellis at Gagosian

Arriving at the 2016 edition of Gagosian‘s pre-Oscar show felt like arriving at LA’s hottest nightclub with an eclectic line that stretched down the block and around the corner complete with hungry paparazzi waiting at the entrance. Inside the gallery was an undeniable energy not unlike a dysfunctional family reunion of the who’s who in Hollywood and Art, including botched surgeries, huge egos, smiley air kisses and all. The place was packed.

Those who came for the art were met with massive walls of collaborative laser-printed paintings by Alex Israel and Bret Easton Ellis, artists who have made a pretty penny using Los Angeles and celebrity culture both as a subject and background in their work. Even the paintings were fabricated at Warner Brothers by the production crews formerly responsible for hand-painting Hollywood film backdrops. And oh what a backdrop they were that night: Instagram photos, endless selfies, and the cringe-worthy “only in Los Angeles” public glam shots in front of phrases such as “I’M GOING TO BE A DIFFERENT KIND OF STAR.”

As the night went on the crowd got dense, loud and littered with A- through D-listers. Israel himself looked painfully bored; Ellis seemed humble and happy to be there; Elton John came and went like the legend he is; Jeffrey Deitch, Eli Broad and Richard Prince made their rounds; Adrien Brody melted hearts with his pony tail and Ryan Seacrest attempted artspeak in the back room. The evening was an undeniably clever commingling of art as entertainment and entertainment as art, exhibiting an output as shallow and plastic as most of its audience. The irony of such was almost too much to handle and definitely too humorous to ignore.

See the show for yourself sans crowds and celebs.

Alex Israel/Bret Easton Ellis will be on view at Gagosian in Beverly Hills until April 23rd.

-

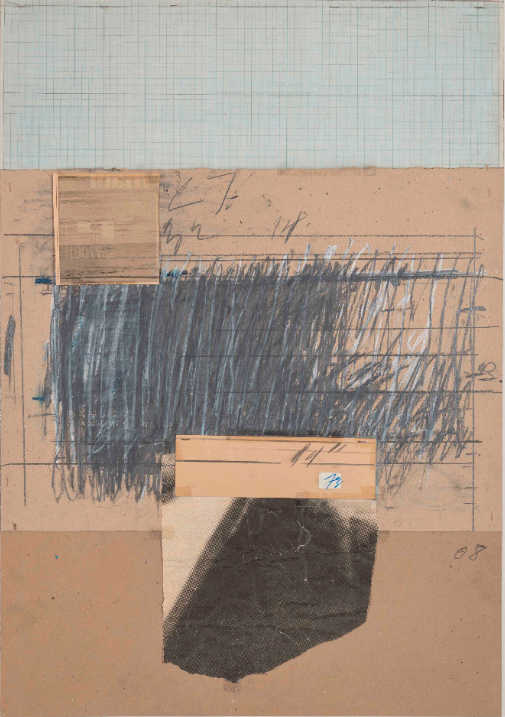

Cy Twombly; a selection of works on paper, 1957-1984

Cy Twombly’s suite of stunningly chaotic and gorgeously rendered free-form drawings at c.nichols project would stop any viewer dead in their tracks. These are ferociously contemporary works that are mandatory viewing for anyone interested in modern art in any meaningful way. They push boundaries, talk back, and slap you upside the head—a celebrated anarchy in all its glorious manifestations. More important perhaps, they are urgent articulations of what it means to be alive and independent in one’s mind and heart.

12613 1/2 Venice Blvd, Los Angeles, CA 90066

Show runs through March 19, 2016

-

Meliksetian | Briggs:

Meg Cranston

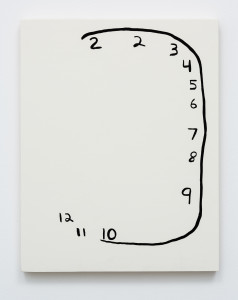

Bubblegum colors and an interest in the mundane are threads that unite the seemingly unrelated pieces in “Pizza, Bagpipe, Carburetor” by Meg Cranston. The show’s conceptual gambit—subject matter selected by Cranston using an internet-hosted random noun generator, an I Ching for the information age—is enlivened by Cranston’s refreshing playfulness that gives her pieces a tangible sense of the humorous. Hickory Rocking Chair (2015), a rocking chair whose seat is composed of bubble wrap, is an excellent example of this humor.

Meg Cranston, Hickory Rocking Chair (2015), courtesy of the artist and Meliksetian | Briggs, Los Angeles. Many of the works, such as Clock with Left Missing (2015), exist in the world of a philosophical thought experiment as Cranston attempts to convey how a subject with brain damage would illustrate a clock. The results of her conceptual questions are diverse and lively, with some works like the aforementioned appearing illustrative and similar to David Shrigley, while others like Dancer (2016) contain more Pop Art, Warhol-esque qualities.

Meg Cranston, Dancer (2016), courtesy of the artist and Meliksetian | Briggs, Los Angeles. Although the space inside Meliksetian Briggs gallery is fairly limited, Cranston’s work manages to produce the sensation of being larger on the inside than the outside. The more the viewer questions the contents of the paintings and sculptures, the more one can fall into the work, and therefore the inquisitive mind of the artist. The implied sexuality within many of the works—the naked rear in Dancer, the sculpture Bagpipe (2015) resembling a scrotum with women cutouts surrounding it, the blurred face attached to a scantily clad female in Yellow Cyclone Gray (2015)—suggests Cranston’s thought process when faced with language that is otherwise unprovocative. Cranston seems to be playing with the duality of what exists and what doesn’t through words and the intuitive searching around in the dark for the associative meaning of them, and from that searching comes a heady show that doesn’t take itself too seriously.

Meg Cranston, Clock with Left Missing (2015), courtesy of the artist and Meliksetian | Briggs, Los Angeles. Meg Cranston, “Pizza Bagpipe, Carburetor,” January 23- March 5 at Meliksetian Briggs, 313 N Fairfax Ave, Los Angeles, CA 90036, www.meliksetianbriggs.com.

-

MAK Center:

Erwin Wurm

Erwin Wurm’s “One Minute Sculptures” at The MAK Center is crammed with critically disruptive content, though at first glance there’s not much to look at. In a literalized enactment of the Duchampian observation that “the viewer completes the art,” visitors to Wurm’s show are compelled to activate the works on display with their bodies for one minute. The un-activated work consists of everyday objects, stuff easily purchased in any city, on individual pedestals lit from above, a presentation designed to frame each thing as a work of art. Wurm uses these conspicuous banalities to inspire his viewers/performers to focus on the strangeness latent in the non-art objects we engage with every day, and in doing so he re-frames how we understand their symbolic and real uses. One piece has you put a sneaker on your head. Another has you stand like a flamingo while propping a drumstick between the back of your heel and the back of your knee. Another has you wrap your head in a pink stuffed animal. Each action is ridiculous both to perform and witness. To write this review, I did my duty and interacted with each work. I ended up with a bucket on my head and my mind thoroughly blown.

Tucker Neel activating The Half-truth (2016), a One Minute Sculpture by Erwin Wurm at The MAK Center. Photo by Tucker Neel. Wurm has been exhibiting these works for almost 30 years in major art institutions around the world, and much has been made about his ability to blur the lines between sculpture and performance. But in the world-famous Kings Road house designed by architect R.M. Schindler to embody idealist notions of communal living, Wurm’s one minute sculptures inject a funny and biting critique into a place many fans of architecture treat like a holy site.

MAK Center, Schindler House. Photo by Joshua White. Courtesy of The MAK Center. Back to the bucket on my head. I was urged to put it on by Twilight (all works 2016), Wurm’s most compelling work in the show. It consists of a rough-hewn DIY wooden table and lamp combo topped with a shade made from another overturned plastic bucket, emblazoned with the logo for “Do it Best Quality Paints.” I can’t help but see this bucket / lampshade as a nod to painting’s absence, not just in this show, but to Wurm’s particular artistic practice. Twilight is next to a table and chairs that are part of the house, designed by Schindler himself, and a sign asks visitors not to sit on the revered architect’s stuff. The juxtaposition of Wurm’s interactive, cobbled-together furniture and Schindler’s preserved specimens creates a tongue-in-cheek critique of “use value,” investigating what a chair actually is if you can’t sit in it. Additionally the work, with its DIY, almost Dwell magazine attitude creates a space for considering the legacy and fetishization of mid-century modernism, the way its corresponding aesthetic has become more a lifestyle brand than the instance of radical politics made real. I may have looked silly with that bucket on my head, but putting it on helped me see Wurm’s work, and the MAK Center, and art in an inspiringly new way.

Erwin Wurm, “One Minute Sculptures,” January 28 – March 27, 2016 at MAK Center for Art and Architecture, Schindler House, 835 N Kings Road, West Hollywood, CA 90069, http://makcenter.org/.

-

Editor’s Letter

You’ve heard the one about how sculpture is something you bump into when backing up to look at a painting. An old boyfriend who was a sculptor told me that joke.

He also told me the story about how Louise Bourgeois was at a high power dinner with an all-male sculptor guest list, being wined and dined as prospective artists for a commission. When the job was described as for someone who really had balls, apparently Ms. Bourgeois stood up from the dinner table and shouted, “I got balls!” That story is always fun to tell and one hopes it’s true. The point being that sculpture was once a man’s game and arguably a secondary modern art form compared to painting.

A few years back we did an issue about painting. This time around, we decided to address sculpture. It turns out that sculpture is going strong. As somebody who has been known to dabble with a paint brush on occasion, I’m aware that there are two types of artists: those who work on a flat surface, and those who create 3D art. I was lousy at ceramics and sculpture but thrived with pen or paintbrush in hand. Is it the way we are wired? I think so, although some artists succeed at doing both. Take our cover artist, Aaron Curry. His sculpture is as manly as Richard Serra’s, and his paintings are just as accomplished—although the 2D works do take on a spherical quality with their shaped canvases and tubular, outer-space content (looking suspiciously sculptural).

Perhaps oddly, female sculptors outnumber males in this issue, but only by accident. Could it be because the ancient tools of the sculptor—hammer and chisel, welding torch, lost wax casting—are no longer necessary when sculpting (thereby not requiring the fair amount of brawn it used to require to perform such tasks)? Materials used in creating 3-dimensional objects these days include cardboard, yarn, fabric and found objects. Some are created on computers, far from the original meaning of sculpting: to carve.

Another medium gaining popularity is clay, also known as ceramics, and it can be very hands-on. Regular contributor Scarlet Cheng just scores the surface on clay sculpture today. She focuses on Matt Wedel, Tanya Batura, and Phyllis Green, who has been working with the mud substance for decades now. Teapots, ashtrays and bongs have been cast aside for busts, flower trees and larger-than-life objects. Kilns are heating up.

But can it be classified as sculpture? Art critic/professor Frances Colpitt questions this in her article on the death of sculpture. She is inspired to continue the conversation with the late Donald Judd from his famous 1965 essay, “Specific Objects,” on the topic.

When you get right down to it, it’s all just art. And I have bumped into it when I was backing up to look at a painting.

-

The Thing

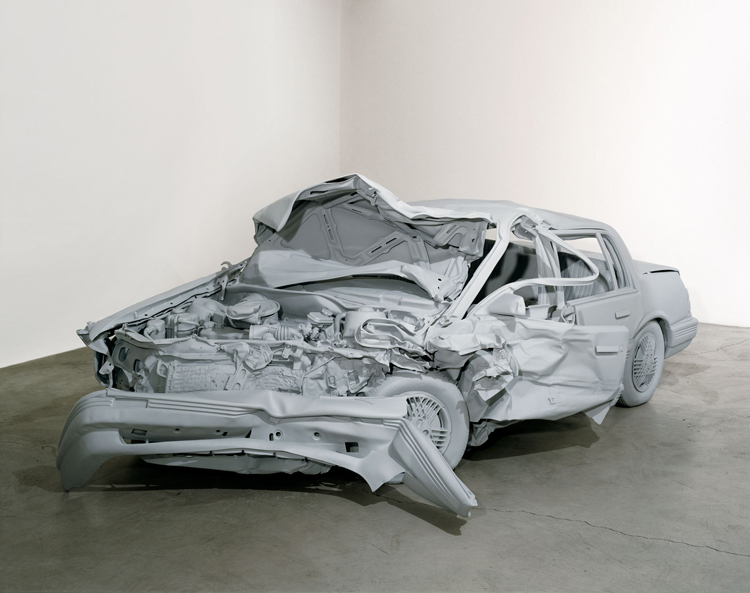

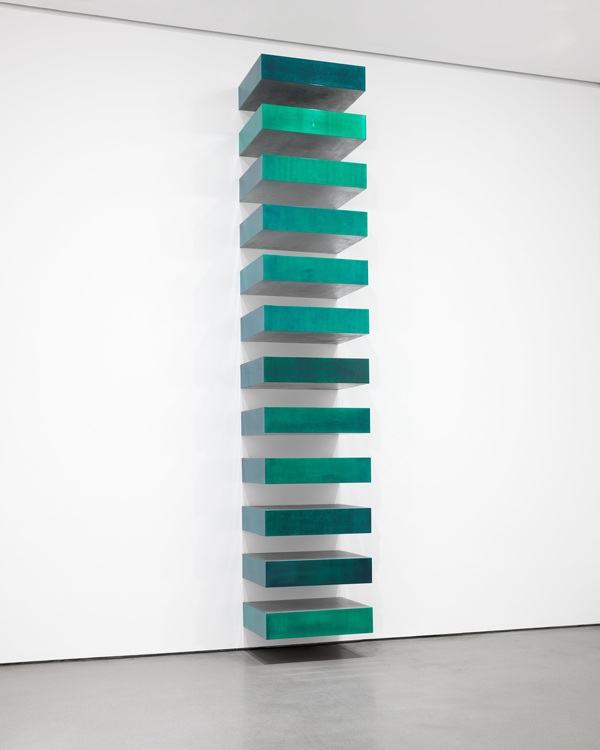

The “death of painting” is frequently traced to the work and writing of Donald Judd. In 1965’s “Specific Objects,” the same essay in which Judd outlined painting’s limitations—above all, its inherent illusionism—he even more forcefully predicted the death of sculpture. Describing sculpture at the time as a “set form” or “a certain kind of form,” he wrote, “it can probably be only what it is now—which means that if it changes a great deal it will be something else, so it’s finished.” He adamantly maintained that his own works, and those by such fellow artists as Dan Flavin, Robert Rauschenberg and Claes Oldenburg, were not sculptures but objects. Shortly after Judd’s article was published, critic Lucy R. Lippard organized the exhibition “Eccentric Abstraction,” which included, among others, Eva Hesse, Louise Bourgeois and Bruce Nauman. Her catalog text emphasized the “nonsculptural” quality of their three-dimensional objects, describing conventional sculpture as an “apparent dead end.” None of this is to suggest that traditional sculpture wasn’t still being made by Anthony Caro, Mark di Suvero and many others. It is to say that the sculptural idiom, as old as art itself, was exhausted and obsolete.

Donald Judd, Untitled (Stack), 1967, lacquer on galvanized iron, 12 units, each 9 x 40 x 31″, The Museum of Modern Art, NY, ©Judd Foundation, licensed by VAGA, New York. Historical as well as modern theories of sculpture, much more than those of painting, emphasize its materiality: how and from what it is made. The Latin verb sculpere means, in fact, “to carve.” In an unpublished interview with Prudence Carlson, Judd said, “I don’t like to use the word sculpture because it’s carving to me.” The subtractive process of carving was later supplemented by the additive process of modeling (made permanent in bronze casts) and for centuries these two techniques defined the art of sculpture. With Picasso’s invention of construction in 1912, which was augmented by his appropriation of industrial welding in 1928, sculpture’s vocabulary was greatly expanded. The problem, as Judd often pointed out, is that construction (and assemblage) are by nature compositional and based on the juxtaposition of multiple parts. Whether carved, modeled, or constructed, sculptural compositions, unlike singular, whole objects, are arranged according to the sculptor’s sense of balance, individual style, or personal expression.

Another defining convention of sculpture is its subject matter, which was, with rare exceptions, the human figure. Most abstract sculpture retained a more or less obvious anthropomorphism that Judd associated with “statues” (the Latin word for sculpture is statuaria). As Robert Morris, Judd’s minimalist colleague, wrote in 1969, sculpture “was terminally diseased with figurative allusions . . . . Sculpture stopped dead and objects began.” The Russian constructivists were among the few modern sculptors to produce wholly nonreferential forms; others like Malevich and Vantongerloo ended up with architectural, in place of human, references. On purely abstract terms, most sculpture was unable to compete with painting and therefore rendered only conditionally modern. Characteristic of sculpture is its material existence as—if not a substitute person—a thing, and potentially some-thing, in the world. Because it was man-made with industrial materials and techniques, minimal art was often compared to furniture. While sculptures were aesthetically differentiated from real things by the use of a base or pedestal, objects were displayed directly on the floor, undifferentiated from desks and tables.

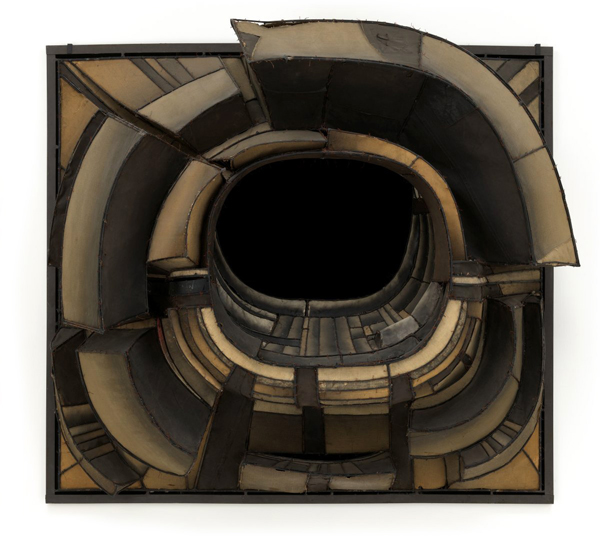

Lee Bontecou, Untitled, 1961, welded steel, canvas, black fabric, rawhide, copper wire, and soot, 6′ 8 1/4″ x 7′ 5″ x 34 ¾”, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Kay Sage Tanguy Fund. Rather than extending sculpture’s trajectory, minimal and postminimal objects derived from the tradition of painting, the preferred medium of modernists. The intermediary step between paintings and objects was the wall-hung relief in which the shape of the support coincided with the depicted image. In painting before the 1960s, the canvas’s rectangular frame enclosed assorted and dispersed shapes; in shaped paintings such as Frank Stella’s, the framing edge was determined by the pattern of stripes or, in Lee Bontecou’s reliefs, the protruding surface was shaped by the dark voids and copper webbing of her imagery. The shaped canvas and relief were more object- than window-like, drawing attention to the gallery space in which they were presented. Occupied by the powerful presence of a simple volume like a box, plank, or slab and a kinesthetically alert beholder, the room’s charged space is part of the artwork and the experience.

Floor Cone (Giant Ice-Cream Cone), 1962. Claes Oldenburg. Already in 1964, Lippard was cognizant of the “anti-sculptural” trend exemplified by objects that incorporated their environment. Environmental artworks, she explained, are “extrovert” and “surround the viewer.” In addition to Judd’s first show of three-dimensional objects, her Artforum review included Stella’s “purple polygons” at Castelli Gallery (“These paintings are real objects,” she wrote) and Oldenburg’s all-vinyl Bedroom (1963), a life-size tableau of a bedroom suite. The category of environments, she noted, also included George Segal’s tableaux with white plaster life-casts of men and women, happenings performed by real people and object-based or participatory group shows. Commissioned by Arts magazine as a report on the proliferation of three-dimensional work then on view in New York, Judd’s “Specific Objects” essay identified two divergent directions: artworks that are objects and those that are “open and extended, more or less environmental.” Oldenburg was also featured in Judd’s report; soft sculptures such as Ice Cream Cone qualified as an object while Bedroom was an environment.

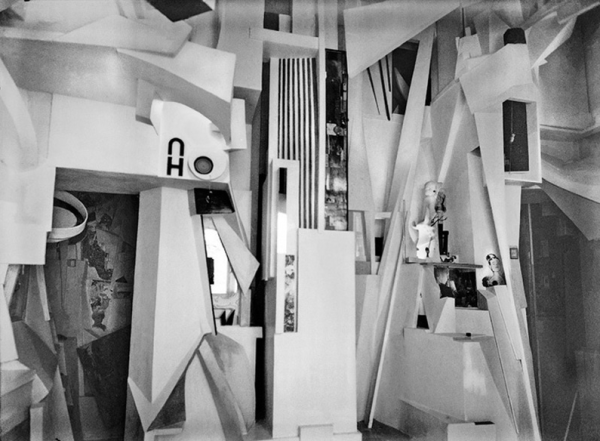

Kurt Schwitters: Reconstructions of the Merzbau, Tate One of the most insightful but overlooked essays on environmental art is “20th-Century Period Pieces” (Arts, February 1967) by Ricki Washton (now Rose-Carol Washton Long). She traces its genesis to Schwitters’ Merzbau (1933), Rauschenberg’s combines, Kienholz’ early ’60s environmental tableaux and Lucas Samaras’ Mirror Room (1966), an enterable room with table and chair completely sheathed in plate glass mirrors, creating infinite cascades of reflections. None can be assimilated to the less elastic category of sculpture. Identifying the art environment with the popular nightclub Cheetah and the ideology of Timothy Leary (“tune in, turn on, drop out”), Washton predicted the eventual “transportation” of such period-defining rooms to museums and the unprecedented possibility that “the museum could provide empty rooms in which the artist could work out environmental settings.”

Like other perceptive critics, Washton identified Allan Kaprow’s art and theories as foundational. In his 1956 essay, “The Legacy of Jackson Pollock,” Kaprow argued that the recent history of painting led directly to the (as yet unnamed) happening, an art form he initiated in 1958. Taking Pollock’s mural-scale drip paintings as his inspiration, he explained that “they ceased to become paintings, and became environments… The entire painting comes out at the participant (I shall call him that, rather than observer) right into the room.” Happenings were entirely dependent on participants, who followed Kaprow’s lists of scripted and improvised activities in environments incorporating sound, movement, language and materials ranging from used tires to blocks of ice. Proving Judd’s point that three-dimensionality “opens to anything,” happenings and environments were widespread preoccupations of the period, represented by Fluxus, Light and Space, Japanese Gutai, late School of Paris (Georges Mathieu and Yves Klein), Austrian Actionism, Brazilian Neo-Concretism (especially Hélio Oiticia’s interactive environments), Red Grooms, Womanhouse and performance art.

This crucial juncture in the history of contemporary art marks the beginning of the end of modernism. Environments were distinguished by their rejection of one of the definitive characteristics of modern art, medium specificity, which stipulated that each medium (painting, sculpture, music, poetry) had a unique function and capability that made it the most appropriate option for an artist’s idea or expression. As critic Michael Fried sarcastically observed in 1967, “the arts themselves are at last sliding towards some kind of final, implosive, highly desirable synthesis,” as a result of the new developments that evoked the mixed or “impure” medium of theatre. Specifically targeting Morris and Judd, Fried also condemned Kaprow, Joseph Cornell, Rauschenberg, Oldenburg, Flavin, Smithson, Kienholz, Segal, Samaras, Christo and Kusama for their amalgamation of painting, sculpture, objects and environments, categories that Judd’s “Specific Objects” had carefully differentiated. While Kaprow and Washton celebrated the conglomerate environment, other artists recoiled from the non-art implications of distraction, fun and entertainment associated with everyday life. In essays and interviews, Morris stalwartly denied that his art was environmental. Flavin’s installations of fluorescent lights were also frequently described as environments, which, he said in 1967, “imply living conditions and perhaps an invitation to comfortable residence.” The raw intensity of the light and the buzzing of the fixtures were intended to be “direct and difficult.”

Judy Pfaff, Installation Deepwater As readers thus far have surely suspected, “environments” became “installations” in the late ’70s. The fact that the work surrounded the viewer and required his or her participation remained definitive aspects of installations. The incorporation of the beholder’s body and its heightened kinesthetic response were more fundamental to the theory of installation art than to environments, due to the increasing influence of Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s philosophy of phenomenology. Informing but only implicit in Morris’ key text on bodily awareness, “Notes on Sculpture, Part 2” (1966), Merleau-Ponty’s interpretation of perception was body-bound and multi-sensory. The term “installation,” which had only referred to the placement and relationship of individual works of art in a gallery, now described a room-filling whole, a single piece in which the parts themselves were not detachable works. Judy Pfaff’s Deepwater—composed of painted tree branches, wire, wicker, reflective Mylar strips and swaths of bright colors like turquoise and pink—at Holly Solomon in 1980 was one of the first to be widely and without hesitation described as an installation. Here Pfaff recreated the experience of snorkeling in the Caribbean, immersing the viewer in a vibrant aqueous totality. Jonathan Borofsky’s installation at Paula Cooper, also in New York in the fall of 1980, surrounded the viewer with a seemingly random distribution of objects, a large Hammering Man, an animated video, paintings, wall drawings, even a ping-pong table to be played by viewer/participants. Tying it all together was the floor, which was littered with crumpled photocopies of a handwritten flyer found on the Venice boardwalk. Unlike the fluid, cohesive experience of Pfaff’s show, Borofsky’s was chaotic and fragmentary, conveying, he said, “the sense that you are inside my head.” By the time that Ilya Kabakov—often credited as an original installation artist—began making illusionistically convincing environments in 1983, installation was a well-established format. The term is now used so carelessly that its original meaning, which refers to the arrangement and display of independent artworks, has been conflated with the genre of art that transforms a space into a singular, experiential totality, as Claire Bishop has pointed out.

The same linguistic laziness affects our use of the word “sculpture,” which is applied to any three-dimensional work of art, including installation. Just as Duchamp deplored the identification of his readymades as sculpture and object-makers were purposefully not sculpting, most three-dimensional art is not sculpture in the original sense of the word. Overcoming the limitations of sculpture, objects and environments have prevailed for the last 50 years.

Not until the ’90s, according Roberta Smith’s analysis of Judd’s early innovations in 2002, was sculpture once again viable. Robert Gober, Kiki Smith, Charles Ray and Jeff Koons, to whom I would add Rachael Harrison and Isa Genzken, reestablished the medium of sculpture. Their figurative or anthropomorphic compositions convincingly affirm the sculpted statue of yore.

-

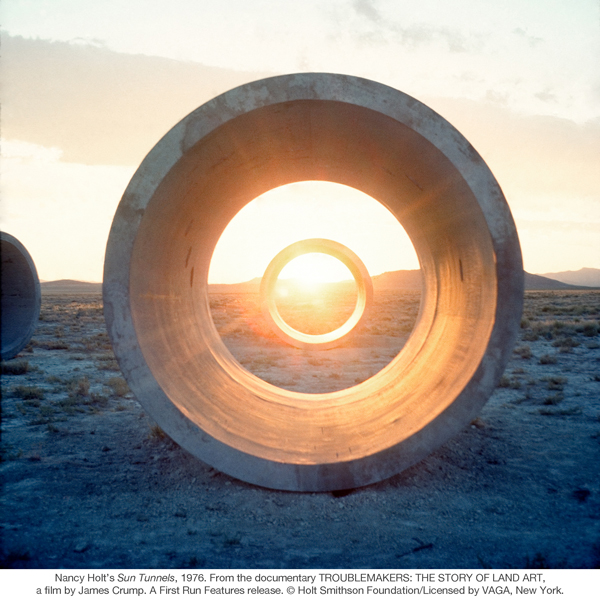

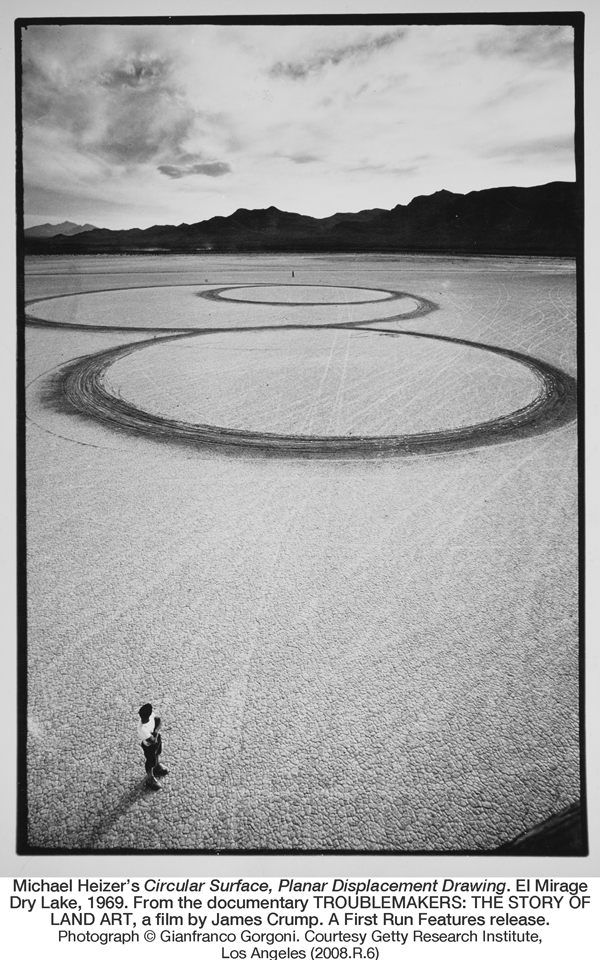

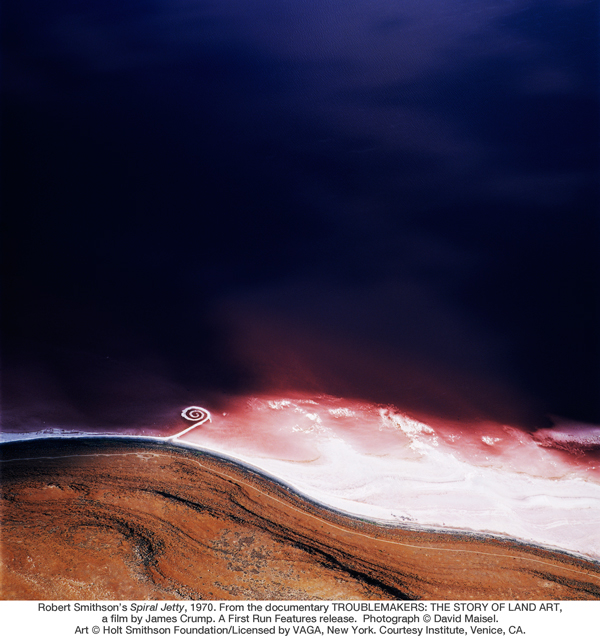

FILM: Troublemakers

Land Art, also known as Earth Art, emerged in the period that was, with hindsight, clearly one of the most radical, innovative, experimental and groundbreaking periods in the history of art. The genre is part of a much wider trend that falls under the umbrella of conceptual art, and represented a shift away from art as a commodity and towards the dematerialization of the art object. Ironically, in these times in which art objects are being collected frenetically, the movement has finally received a proper documentary. Art historian, curator and filmmaker James Crump’s Troublemakers: The Story of Land Art is a long overdue tribute to this iconic era. Combining rare documentary footage from the epoch’s heyday in the 1960s and ’70s with contemporary interviews with artists who were active in that period (some key practitioners are now dead, including Robert Smithson, who died in a plane crash while working on Amarillo Ramp at the tender age of 35), the film manages to capture some of the wonder evoked by a visit to one of these sites.

The documentary is impressive because of its scholarly approach to the subject, carefully presenting it in the context of those tumultuous times, and clarifying the relationship between Earth Art and the myriad of conceptual activities that were happening concurrently. Testimonies from artists such as Minimalist Carl Andre and Conceptualists Vito Acconci and Lawrence Weiner along with filmed footage of the New York art scene help to capture the zeitgeist, one very different from that of today’s art world. Also of great interest are the sections devoted to Willoughby Sharp and Virginia Dwan, who both contributed to the movement by supporting it; Sharp through his short-lived, iconoclastic magazine Avalanche; and Dwan through her galleries in Los Angeles and New York, particularly through her direct financial support of Smithson and Michael Heizer (she was an heir to the 3M fortune). Recent interviews with Dwan are important additions to the Earth Art archive since she had such close associations with the principal artists.

The film focuses primarily on Smithson, Heizer and Walter De Maria, the best-known artists for works in the landscape, but also includes Dennis Oppenheim, Charles Ross, Nancy Holt and James Turrell. Amongst the documentary’s highlights is the recent footage of Heizer’s Double Negative (1970), near Overton, Nevada. While keeping in mind that earth art can only be experienced firsthand (Heizer even forbade MOCA to exhibit photographs of his outdoor works for their “Ends of the Earth” exhibition in 2012), the extensive footage of this seminal work provides what must be the closest approximation yet to actually visiting such a site. Approaching the piece from every conceivable angle and from aerial views (the way these works are usually documented in photographs but seldom seen by most visitors) the film allows viewers to mentally assemble a complete gestalt of the work.

Although provocative, the film’s title, Troublemakers, does not really capture the true spirit of this singular kind of artwork. Yes, the artists were radically breaking away from the usual traditions of art-making and exhibiting, and many, such as Heizer, have reputations for being “difficult.” (Smithson is described as being “satanic” and having a “dark side.”) But the artists were clearly not out to create trouble for anyone, they simply had big ideas, huge ambitions and boundless energy. Far from creating trouble, the Earth Art experience puts us in touch with the divine, helping us to contemplate our place in the cosmos as we cling to the sphere we call planet Earth.

One of the overall concerns of this whole group of artists (which includes Conceptual and Performance artists) was to get away from the notion of artwork as a commodity. As Heizer remarked, “There are no values attached to something like this… it’s not worth anything; in fact, it’s an obligation.” Paradoxically, these works are only possible through the expenditure of vast sums of money, generally provided by wealthy visionaries like Virginia Dwan, Heiner Fredrick and the Dia Foundation. The end result is that we may experience them as works of art alone, unencumbered by associations of the staggering millions being paid currently for Rothkos, Bacons and Picassos. Can one ever look at a painting that sold for $140,000,000 without being influenced by that fact? Fortunately, Earthwork artists found a way to subvert this; the price we pay to experience them is not monetary but a journey akin to a religious pilgrimage. Troublemakers is an important historical document of a time when rather than embracing and manipulating the art market, artists actually chose to avoid it.

-

Mud Gets Off the Ground

Ceramics is again making a major splash in the world of fine arts. Way back in the 1950s Peter Voulkos pushed ceramics into that realm, with his Abstract Expressionist pieces of cut and contorted clay slabs, followed by the works of his students (among them, John Mason, Ken Price, Paul Soldner) and others who continued to establish ceramics as sculpture. Today über-gallery Gagosian is pushing Edmund de Waal, whose work is made up of exquisite little teacups set just so in custom-made metal frames or on custom-made metal tables. They’re beautiful installations, but they are still… teacups, handmade from porcelain.

Kristen Morgin, Topolino, 2003. Perhaps it was Kristen Morgin’s remarkable dilapidated vintage car—made of unfired clay, cement and wood—in the landmark “Thing: New Sculpture from Los Angeles” show that signaled to me a new generation working with the medium, in what I’ll call the Clay Sculpture movement. That was 2005 at the Hammer Museum. Since then, a number of gifted Southern California artists have often used clay as the basis of figurative sculpture. Generally, such sculpture is made from wood, stone, bronze and other metals—partly because of tradition, and partly because clay has been seen as a lesser medium. In the hands of these artists, clay achieves parity with those other materials—first, by assuming clay can do just about anything the traditional sculptural materials can, and perhaps more; second, by playing with scale; and thirdly, by introducing a conceptual framework. In the Clay Sculpture movement, works are brought off the table and off the shelves and onto the floor and onto pedestals. These works are large, some life-sized, as in the case of Morgin and Ben Jackel, and some larger than life-size, as in the works of Tanya Batura and Matt Wedel. (Their precursor, the San Francisco-based artist Viola Frey, made ceramic sculpture on a gigantic scale, and Wedel has been moving in that direction.)

Phyllis Green, Christine, 2003, ceramic, acrylic, 12 x 8 x 8”, collection of Lynn Aldrich, photo by

Ave Pildas.“It’s a sculpture material that most people can handle,” says artist Phyllis Green, who has been working with clay for 40 years and also teaching for half of that time. “They can form something without a lot of technical experience or know-how, although it’s complex when you want to make something particularly large.” Green has made several series of figurative sculpture using low-fire clay, although she completes them with other kinds of finishes, not traditional glazes. For the series “Odd Old Things,” abstracted torsos dressed in tutus, she used synthetic rust coating; for “Spinning Heads,” invoking whimsical mops of women’s hairdos, she used acrylic finish and varnish.

“I came to clay by accident,” says Tanya Batura, an artist known for busts of bald white heads displayed on pedestals. They are usually tilted and sometimes have highlights of red around the mouth, giving them a sensuous, erotic quality. “When I was at Manchester Community College, I started taking ceramics classes,” says Batura, who grew up in Connecticut. “I became more and more involved in it, till I recognized that was my focus.” Later she transferred to the University of Washington in Seattle, and finished her BFA in 1998. Two years later, she enrolled in the MFA program at UCLA, where she was a student of Green’s.

Tanya Batura, Untitled (side detail), 2015, clay, acrylic, 16 x 12 x 12.5″. In Los Angeles she felt she had to rethink her work, and she found inspiration in an unusual place—by walking into the Medical Library. “I came across a book on plastic surgery,” she says. “It was one of those Aha! moments. I was already thinking of erotic, sensual imagery—all those fashion magazines with close-ups of mouths.” She began the head series at UCLA, making some all–dark brown and some all-white. “I really love how light plays off the heads,” she says. “It’s more about form and less about surface, and the white looks like a canvas.” She has continued with the heads, leaving them white “because it’s more neutral, it also helps harmonize the work.”

Her figures are formed by hand, and she starts by building up coils of low-fire earthenware clay. Then she shapes the features—eye sockets, nose, mouth and so on—using her fingers and basic tools. “I’m always smoothing when I’m building,” she says. “I sand them after they’re fired, and then they are airbrushed with many layers of thin acrylic paint.” She sands in-between coatings, so that the surface is preternaturally smooth. Recently, she has been slashing at and piercing the smooth surface—scarring the heads, in a way. “It has the energy and activity of the mark-making,” she says. “It’s disturbing to some people to damage something so perfect, but I think of it as another form of deconstructing something.”

Matt Wedel, Flower Tree, 2015, ceramic, 77 x 74 x 69″, ©Matt Wedel, courtesy L.A. Louver, Venice, CA. Matt Wedel is a ceramic artist, also educated in SoCal at Cal State Long Beach, who has taken clay to another level. He studied with Kristen Morgin and Tony Marsh, and now lives and works in Ohio. “My dad’s a potter, so I grew up in his studio, working with material,” he says. Later, when he became an artist, “I found myself approaching ceramics in the context of sculpture as a place to begin. It became a platform for me to work.” Wedel actually found a certain freedom working with clay. “It seems like it was a place I could exist without following so many rules. No one was paying attention, I could just be on my own.” His recent show at L.A. Louver, “Matt Wedel: Peaceable Fruit” showed him exploring some of the same forms and ideas as before—strange flowering plants with intertwined tendrils, rotund humans who seem almost mythological in their generalized appearance and classical postures.

“Initially the works were landscape-based,” he says. “Figures emerged as symbols of culture amidst the landscape. Now the figures have become ways of keeping alive or continuing historical narrative, symbols of moving forward or some kind of reconciliation with culture itself.” His figures have also become very large—the people can be bigger than life, and a “Flower Tree” can be six feet tall. Unlike Green and Batura, Wedel uses ceramic glazes to finish off his work, with the yellows, greens and turquoises sometimes melting into one another, as fired glazes will.

“As artists we try to find materials that we feel fully engaged with,” says Wedel. “I make the clay figures, I glaze them, fire them in studio, some in sections. It’s exciting to make everything myself.”

UPCOMING EXHIBITIONS: Tanya Batura: “Lineage: Mentorship and Learning” (through June 19) at the American Museum of Ceramic Art, Pomona, “Observations” (through March 17) at Long Beach City College; Phyllis Green: “Re-Walking” (through March 24) at the José Drudis-Biada Art Gallery of Mount St. Mary’s University, Chalon Campus, West Los Angeles.

-

Fueled by Youth

The sculptures of Sergio Garcia contain an otherworldly essence. Like relics from an alternate dimension created by Salvador Dali, Henry Darger and Kaz Oshiro, Garcia’s surreal concoctions teeter on the brink of absurdity and play with the experience of living and growing in contemporary society.

This second-generation Mexican-American Dallas-based artist discovered that he had a gift for graffiti, realism and mural painting in his youth, but it wasn’t until a curatorial opportunity came up for him in Dallas that he began to see the multitude of possibilities at his fingertips. In 2009, after six or seven years of paid painting and mural opportunities, Garcia resurrected a new sense of purpose when he ventured into the realm of sculpture, making a child-sized tricycle, without utility, that invoked the rebellious energy of Marcel Duchamp. His altered tricycles astounded people and received immediate attention from art collectors and galleries. His sculptural debut was at Kirk Hopper Fine Art in Dallas in 2009, under his own curation, but gallery owner Kirk Hopper inspired Garcia to explore his three-dimensional talents further.

Sergio Garcia, “We all get a little side tracked,” 2014, mini-tricycle, metal, plastic, automotive paint, 11″ x 8″. After he was kicked out of his art-magnet high school, Garcia’s education was limited; he relied heavily on his own research, his practice and the influence of his peers. Quick-witted and naturally creative but a poor student, he gave himself over to the one thing he felt best at above all else—art. Now, at 35, Garcia speaks at universities, high schools and even prisons, about techniques, processes and creativity. He still shows with Kirk Hopper, but his resume has expanded to include Thinkspace Gallery in Culver City, Shooting Gallery and White Walls Gallery in San Francisco, Frosh and Portmann in New York, and he has exhibited at many art fairs across the country.

Sergio Garcia, “Pink Heart (mini trike),” 2014, mini-tricycle, metal, plastic, automotive paint Garcia’s furniture-based sculptures are filled with irony and perception. With his twisted or knotted shiny vintage bikes or never-ending vintage school desks, Garcia visually comments on the experience of life, of growing, and of being a powerless child. His works have a unique attraction, their symbolism and representation seeming to summon up a deep resonance to life experiences.

Sergio Garcia, “Just the thought of you,” 2014, fiberglass, cloth, and blown glass, 60″ x 24″ x 20″ Garcia cites his adolescence as a prime inspirational source. Having grown up on the outskirts of Dallas with non-English speaking parents and a fondness for skateboarding, tattoos and graffiti, Garcia makes his own history clear, in his clean and high-finish works. With its symbolism, whimsy and visually interesting references to different eras, cultures and lifestyles, his work disarms and elates viewers, yet it still remains under the high finish umbrella the art world holds so dear.

Sergio Garcia, “It’s like a sculpture but with more breakdancing,” metal and wood school desk assemblage, 66″ x 69″ x 18″ “Regardless of where life takes you or what you become, you’re still the same person you were when you were younger, you just changed the top layer,” Garcia says in an email correspondence. Many of his sculptures play with the idea of childhood, adolescence and irony. He uses a combination of methods and materials to create his fascinating world. His series of hands, arms and figurative works are made with resin, ceramics, glass, metal, enamel and sometimes found objects. But his realistic painting skills bring his work to an entirely different level. Playing on trompe l’oeil, his figures pop out from that alternate dimension and hypnotically pull the viewer closer. Garcia says that people’s reactions to his work are his favorite part of making art. “I feel with my work I can connect and make people smile,” he says. “People’s responses fuel me.”

-

Alternate Empires

As a student, seeking respite from the relatively hidebound painting department, I often retreated to the sculpture studios. There, the critical gaze of teachers seemed less intense; sculpture students did as they pleased. Around that time about a decade ago, I took Beginning Sculpture from Krysten Cunningham, who fostered critical dialogue around fundamental techniques of welding and casting. A recent visit to her Los Angeles studio, as well as that of her neighbor Maura Bendett, and the spacious loft of Camilla Taylor, revived the sense of freedom that I felt as a painter approaching sculpture.

Perhaps, then, it is no coincidence that two of these sculptors began as 2D artists. Painting and printmaking imply certain sets of media; a sculpture, however, can be nearly anything. Yet sculpture is often yoked to a limited set of usually rigid media: metal or stone, for instance; and frequently chained to a sense of machismo. Bendett, Cunningham and Taylor are forging their own paths. Each uses materials commonplace to everyday life, but not to sculpture. Their diverse oeuvres share other basic commonalities: an emphasis on the handmade; engrossments with human and animal societies. From Maura Bendett’s alien ecosystems to Krysten Cunningham’s dynamic weavings to Camilla Taylor’s somber humanoids, their individual concoctions frequently exude an almost animate presence. All three once contemplated pursuing scientific occupations. Like a researcher, each approaches her art as an open-ended investigation.

Maura Bendett’s studio, detail of work in progress, photo by Annabel Osberg. Near an intersection flanked by a stately old manse and a liquor store on a busy stretch of West Washington Boulevard, where sidewalks meet buildings embellished with historic ornament and fresh graffiti, Bendett’s studio occupies a block interlaced with razor wire and ivy.

Bendett’s laissez-faire practice has been guided by her lifelong awe of nature. Fascinated by insects, she originally considered a career in entomology before determining that “it’s mostly about working for extermination companies.” Instead, she decided to become an artist.

As a painting student in UCLA’s MFA program, she took glassblowing and soon became enchanted, spending every spare hour forming alien-like blobs in the hot shop.

This foray affected her painting, which increasingly involved sculptural elements and shaped canvases.Upon graduating in 1987, she found that she wanted to move beyond making art about art, and returned to her core interests, beginning with her penchant for insects: “I felt it was like looking at little dinosaurs. It was like looking at something beyond humanity—way beyond.”

Maura Bendet, detail

Over the next decade, Bendett began incorporating imagery of invertebrates, amphibians, plants and extraterrestrials into heterogeneous objects that combined painting, printmaking, drawing, sewn fabric and other media. In a breakthrough 1997 show at PØST, she exhibited patchworks of drawings interlaced by webs of fishing line. One patchwork in particular, Empire, referred to “the empire of the plant world.”“I was never interested in humans,” she explained. Rather, she wanted to explore our relationship to other organisms and our self-appointed role as the supreme species.

“Vespid Empire,” her 2014 show at Edward Cella Art + Architecture, alluded to Modernist and Minimalist sculpture. Instead of traditional materials, her works were constructed of thickly painted illustration board joined by hot glue. They seemed to teeter with planar instability in equal reference to Futurism and rock formations.“For me, the thing that was most interesting was how I made them,” she said. “So I decided to highlight all the edges.” Colored lines tracing every seam turn each sculpture into a drawing despite its third dimension.

Maura Bendett, Tall Sculpture, 2013, museum board, acrylic, hot glue, cement, 63 x 27 x 27″, courtesy Edward Cella Art + Architecture. In her new work, she returns to her training as a painter, incorporating acrylic paint as a spatial element and looking to painters like Jay DeFeo for textural inspiration. Blobs of paint are only one of many materials, including glass baubles, wires and Plexiglas rods, that coalesce into her sculptural agglomerations. While determining each component’s placement, she contemplates hypothetical configurations like a painter pondering her next brushstroke.

• • •

In a West Adams studio just three doors down from Bendett, Krysten Cunningham also questions hierarchies. In contrast, her concerns center on humanity. Adorned simply with one shiny silver bangle, her sturdy hands bespoke resourcefulness as much as did her anecdotes of camping alone in the Southwestern wilderness, searching for petroglyphs on archeo-anthropological investigations. Our conversation revived memories. In critiques, she had been blunt but kind; she seemed grounded in practicality even while discussing visionary notions.

According to her, the values I observed her promote in her Beginning Sculpture class—curiosity, fellowship and independent thinking—likely germinated in her early life, especially in her upbringing on an intentional farm community in Virginia.

“Women always participated in building the houses on our farm,” she said. “It influenced me for making sculpture because all the women were making things, so I just thought naturally that I would build things.”

Krysten Cunningham, Labor and Technology (detail), 2015 As a teenager, she apprenticed with a local potter. Later, she studied anthropology at Smith College but found the environment confining, so she dropped out and traveled around the country. In Santa Fe, she studied indigenous ceramics at the Institute of American Indian Arts. Eventually, she earned a BFA from the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque in 2000 and an MFA in sculpture at UCLA in 2003.

Chris Burden, her UCLA mentor, sent her to physics research specialists for help with her sculpture involving a Foucault pendulum. This excursion led to a position in the department, where she now produces physics videos. She feels her work in the physics department complements her sculpture practice. Research on quantum encryption, for instance, informed her woven sculptures. Cunningham’s engagement with weaving encompasses its haptic, technological and societal implications. She explained, “I’m interested in technology—how we use it, how we look at it and how we might look at it differently.” In a series titled after the RGB color system, warp and weft are inspired by binary code; woven manifolds are metaphors for digital networks; and squares of interlaced fabric strips resemble pixels.

Cunningham seeks to underscore and overturn the marginalized position textiles occupy as an art form. “[Textiles] don’t share the status of sculpture,” she said. “They’re not elevated. They’re relegated to this: always malleable, always flexible, never solid.”

Krysten Cunningham, Untitled, 2015, performance at Colorado College, photo by Heather Oelklaus In the manner of Neo-Concretists like Lygia Clark and Hélio Oiticica, Cunningham mounts interactive performances with her sculptures. She has encouraged viewers to crawl underneath her weavings and temporarily shape them while partaking in motion analogous to the kinetic efforts of the sculpture’s initial creation. Hands-on interaction affords participants a degree of agency—something she feels contemporary society fails to allow.

“Our voice, our demands, and our humanity are being eroded each year,” she elaborated. “Our civil liberties, and our ability to speak up for ourselves, and our privacy, and our space around us—more and more, we’re self-censoring. So I feel like art can potentially bring that experience back, to make us think outside of how we’re thinking.”• • •

Camilla Taylor’s old-fashioned inclinations coexist with a contemporary outlook. She once sought to acquire furnishings produced in the decommissioned 1930s furniture factory her loft occupies but found their styles didn’t match her taste.

One of her favored mediums is cartonnage, an ancient Egyptian funerary technique. Her pointy, inchoate humanoids morphologically resemble Bendett’s spindled forms. In contrast to Bendett’s reaching “way beyond,” Taylor seeks to excavate humanity’s innards.

Taylor’s early career path parallels that of Bendett. She wanted to be an entomologist. While attending high school in Provo, Utah, she interned with scientists researching wasps. However, on a 1998 bus trip to LACMA, she was so impressed by Michael C. McMillen’s installation The Garage (1981) that she changed her plans. She had always enjoyed dabbling in art; but, never having been exposed to much contemporary work, she had never before realized its conceptual potential.

She earned her BFA in printmaking from the University of Utah, Salt Lake City in 2006. She lost access to the school’s printing presses after graduating, so she began sculpting small figures from clay and fabric. At CSULB, where she earned her MFA in 2011, she fabricated stuffed chimera from cloth prints.

Inside Camilla Taylor’s studio, detail of work in progress that will include 108 cartonnage heads, photo by Annabel Osberg. “I loved the way they had three-dimensional and two-dimensional aspects at the same time, that weirdness of existing in the same space,” she reflected. Though her work has evolved, she continues to strive for that effect. In “Waiting Shadows,” her 2015 exhibition at Bermudez Projects, black sculptures contrasted with white walls to appear flat from afar, like ink drawings. Textural details like strings, stitches and viscid cartonnage slowly emerged as one approached.

“The way someone reacts to a three-dimensional object, to me, becomes so much more personal,” she said. “I’ve never felt protective of a painting. But I feel protective of objects—or more empathy towards objects—because they exist in the space with me.”

Empathy is essential, for she wants her figures to “feel like they’re familiar, like they’re from a subconscious space in the brain.” She acknowledges the influence of Louise Bourgeois, Kiki Smith and Magdalena Abakanowicz, but asserts that her work is neither as confessional nor specifically personal.

Taylor shares with Cunningham a preoccupation with counterposing hardness and softness, and a flair for exaggeration of scale. In Patience (2015), a metal chain suspends a pitchy figure whose grotesquely elongated arms dangle like limp spaghetti, ending in pewter hands on the floor.

Camilla Taylor, It Wasn’t Until Then, 2014, cartonnage, walnut, welded steel, 52 x 13 12” (individually), photo by Mike Reynolds. Lately, she is experimenting with nonobjectivity. A new series called “The Past” is made from failed drawings cut up and stratified like old tomes or fish scales.

A concurrent work in progress will feature 108 tarry heads. “Initially they’ll look like just a pile of coal, but then you start to see that each individual face is different and each one is a different size,” she described.With their indistinct features, fractionalization, and spindly charred limbs, Taylor’s figurative sculptures are redolent of mummies.

“I like thinking about Pompeii,” she said. “Looking at those figures, there’s something universal and undeniable that feels so immediate and intimate. Even though their culture is completely foreign to us, the experience of those figures—we understand them immediately—is so timeless that it becomes this universal language.” She seeks to imbue her sculptures with evocativeness that feels singular yet transcends time and place, like Easter Island moai, the Venus of Willendorf, or Giacometti’s elongated bronzes.

Like those of Bendett and Cunningham, Taylor’s distorted forms challenge conventions while investigating existential questions. Given their intriguing viewpoints and idiosyncratic methodologies, it is little wonder that the three artists unite in their interest in natural science.

Each in different ways, Bendett, Cunningham and Taylor are sculpting alternate empires out of touchstones mined from personal experiences and realms of the past. Cutting free from binding restraints of tradition, each in her unique way has navigated a journey to a fresh vision of “sculpture.” -

ART BRIEF

Stefan Simchowitz is a controversial figure in the art world. He doesn’t own an art gallery yet maintains a large network of art collectors. He eloquently expounds upon art theory but is not associated with an art institution. He provides advice and monetary support to numerous artists whom he claims to have discovered but isn’t a conventional art patron. He doesn’t like to be called an art dealer, but that is basically how he operates. The New York Times Magazine did a profile of Simchowitz early last year, in which they named him the “Patron Satan” of the art world. Simchowitz, who infamously appeared clad only in briefs in a photo accompanying the Times piece, told me that the article is “a work of fiction” typical of the Times’ “bias” against the Los Angeles art scene.

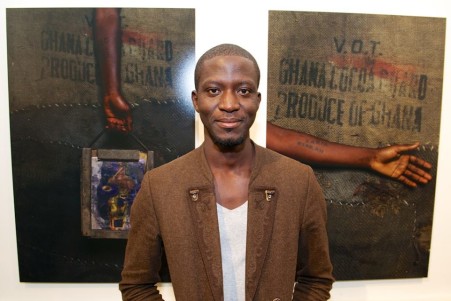

The controversy surrounding Simchowitz has only gotten deeper. In June, 2015, Simchowitz’ company, Simcor, and an associated dealer, Jonathan Ellis King, filed a multi-million-dollar suit in federal court against a young Ghanaian artist, Ibrahim Mahama, who Simchowitz claimed to have discovered on the Internet, comparing him to the red-hot Oscar Murillo, whose works Simchowitz bought early and resold to his group of collectors. Simchowitz is proud of discovering new artists: “No one knows about these artists. There is no market for their work. By providing capital to young artists they have a better opportunity to compete,” he told me in a recent interview about the lawsuit.

Ibrahim Mahama, Civil Occupation, installation at Ellis King gallery, Dec 2014. Mahama’s signature medium for his artworks are jute fiber sacks used in Third World countries as receptacles for commodities from cocoa to charcoal. The artist acquired the soiled sacks for next to nothing and had them sewn together, creating quilt-like works. An installation called “Civil Occupation,” sponsored by Simchowitz and King in King’s Dublin art gallery covered its entire floor and walls during a December, 2014 show. The hundreds of sacks created a mournful cathedral in somber hues of browns and rusts, perhaps an ode to the forgotten laborers of Third World commodities trade who often leave their names or marks upon these sacks.

In the lawsuit, the dealers allege that they made an oral contract with Mahama to pay him about $148,000 in exchange for a large amount of the sacks the artist had assembled. They say some of the sacks were to be used in the gallery installation, the rest were to be made into smaller works mounted on stretchers, a process costing the dealers $67,000. The legal complaint claims that just prior to the gallery show Mahama signed 294 of the works at King’s gallery. The dealers allege they sold 27 of the pieces to collectors for $16,700 each, therefore valuing the remaining 267 works at $4.45 million. They claim Mahama breached the contract by directly selling 20 of the works to an LA collector to finance a massive jute-sack installation for the 2015 Venice Biennale that ran for 300 meters through the “All the World’s Futures” exhibition. It has been reported that an Italian gallery, A Palazzo, currently representing the artist, also provided financing for the Venice installation.

The lawsuit, alleging causes of action for breach of contract, fraud, commercial disparagement, and unfair competition, was filed after Simchowitz and King received correspondence from Mahama informing them that the 294 stretcher works were not authentic and could not be sold since he never agreed to the “commercialization” of his works. Mahama also claimed ownership of the installation displayed at the King Gallery.

Simchowitz told me he spent two years on the Mahama project. “He was using jute coal bags made by migrant laborers for pennies. We assisted him in repurposing them and now they hang on gallery walls as valuable art works.” Simchowitz claims that the A Pallazo Gallery interfered with his relationship with Mahama and told him that Simchowitz was “evil.” He said this was an example of “artists using my money and galleries giving them bad advice.”

Stefan Simchowitz, photo by Rosi Riedl. Simchowitz says he had at least 20 pending deals for sales of Mahama’s works to clients, but now those “deals are dead” and his reputation has been damaged. “Mahama thinks: ‘I’m morally justified to screw you cause you’re Satan according to The New York Times.’” He called Mahama “a two-faced liar” who “forced my hand and I had no option but to sue.”

I also spoke with Mahama’s lawyer, Rizwan Ramji, who told me a much different version of events. He said that Simchowitz did not “discover” Mahama—instead Ellis King attended a London show of Mahama’s work in 2013 and met the artist at the Frieze London art fair and it was only after a deal was made with King’s gallery for a show that Mahama learned that Simchowitz was the principal financier behind King. Ramji said that Mahama shipped four large packages of jute sacks from Ghana to King’s gallery and some of those shipments were used when the works were cut onto stretchers. The lawyer says that Simchowitz “intimidated” the artist into signing the backs of the stretchers for each of the works “under duress.” He says Mahama didn’t care for Simchowitz who is “used to using his money to get his way.” He says that as a result of the lawsuit, the A Palazzo gallery must use letters of authenticity when they sell Mahama’s works.

Artist Ibrahim Mahama at A Palazzo Gallery, Booth G11 East Wing © Sébastien Gracco de Lay As for the lawsuit, Ramji said that he will file a cross-complaint on behalf of Mahama for breach of contract and violation of the artist’s rights of publicity, including using his name and likeness without his permission. Mahama may also claim violation of his rights of droit moral, since Simchowitz “destroyed the integrity” of his artworks by ordering them cut into hundreds of smaller works.

Simchowitz takes a dim view of many of the other artists he has worked with. He told me that many prominent artists, such as Sterling Ruby, are “careerists” who are “consumed with money.” He adds, “The avant-garde is dead. Artists have been mythologized, but they are not cutting off their ears or going off to Tahiti anymore. Artists think they have moral rights and can just breach contracts.” He is furious with former artists he’s represented such as Parker Ito and Christina Rosa, claiming their “careers crashed” after they left him. He also mentioned artist Torey Thornton whom he has openly threatened to sue.Simchowitz, who has been banned from a number of galleries, sees his role as “flattening hierarchies” in the art world. “Galleries protect their legacy systems, but this doesn’t work anymore—we’re in a different world,” he says.

Simchowitz clearly sees himself as a maverick out to smash the prevailing art-world paradigm of major collectors, multinational galleries and big auction houses that set the ground rules of the art world. This may be an admirable goal, but whether or not he succeeds in creating a new paradigm, his version of the art world will still be about the money and consequently some of the artists he “discovers” will probably continue to look for a bigger and better deal. -

UNDER THE RADAR

We are in the midst of the information age, with archives and libraries overflowing, and records piling up like plastic in the ocean. How does personal value translate to cultural value, or is it the same thing? Who decides what is worth preserving? How should collectors and archives and individuals interact?

These are questions posed by author/sound curator/musician/audio artist Robert Millis in the introduction to his lavish new 244-page, full-color hardcover-book-and-double-CD package Indian Talking Machine, a highly personal account of his stint as a Fulbright Scholar in 2012-13 studying the early music industry in India.

Robert Millis in Bangalore While he’s referring specifically to his encounters with an eccentric cast of 78 RPM hoarders in the second-most-populous country in the world, he could easily be describing the driving questions behind most of his own icebergian activities, of which ITM is just the tip, as well as those of a generation of intrepid amateur songcatchers that seemingly sprang out of nowhere over the last decade or so, and the equally unlikely hipster consumer base that eats this stuff up.

As one of the mysterious co-conspirators (along with former Sun City Girl Alan Bishop) of the indie world-music record label Sublime Frequencies, Millis has a legitimate claim as one of the architects of the New Model Ethnomusicology, which celebrates impure hybrids, avant-garde recontextualization, and radical auditor subjectivity—beautiful fragments of street music performance emerging fading from urban soundscape recordings; collages of bootlegged shortwave broadcasts; compilations of vintage Cambodian pop music cassettes scavenged from public libraries in California.

Millis’ particular specialty has been collections of 78 RPM records, including the unimpeachable Burmese Crying Princess and Scattered Melodies: Korean Kayagum Sanjo collections for SF, and an ostentatiously eclectic book/CD package called Victrola Favorites for the Dust-to-Digital specialty label—the high-tone culmination of the cassette anthologies of old 78s that Millis had been releasing with Jeffery Taylor (his partner in Seattle-based experimental band Climax Golden Twins) since the mid-’90s.

HMV sleeve detail That 2007 publication bears considerable resemblance to Indian Talking Machine, largely because it shares the same designer—John Hubbard, who excels at establishing and modulating moods from sequences of documentary photos (though I wish he would recognize the cardinal wrongness of double-truck photo spreads).

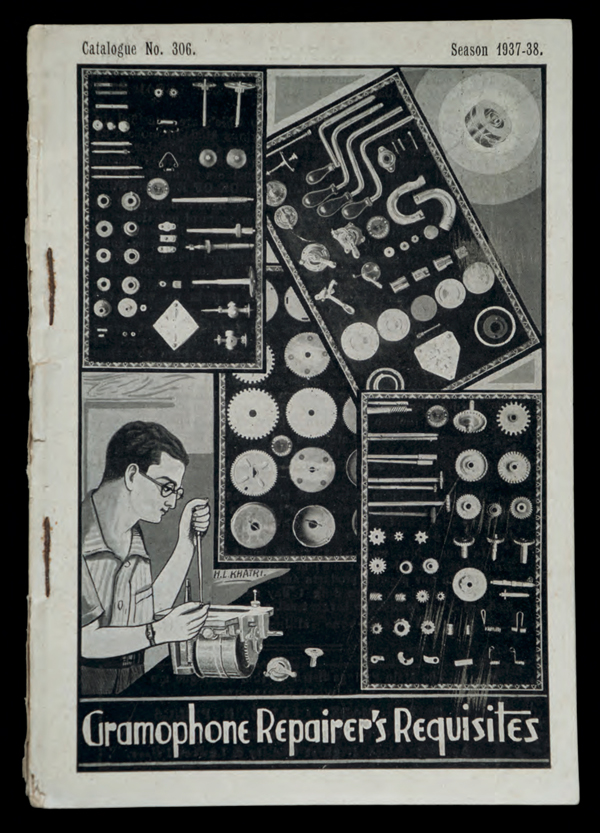

Those looking for an introduction to the vast history of Indian music should seek out a Rough Guide or something. Because ITM consists almost entirely of images—images of moldering stacks of 100-year-old records, crumbling record plants and Victrola stores, collectors poking through their archives, and tons of ephemera—packages of steel styluses, worm-eaten paper sleeves, record catalogs, promo photos, and label upon label—the majority bearing The Gramophone Company’s archetypal catchphrase “His Master’s Voice.”

Which raises a passel of thorny political concerns that are largely unaddressed in Millis’ brief, anecdotal commentary. The British Raj from 1858 to 1947 is pretty much the ne plus ultra of insidious cultural imperialism, and HMV’s wholesale appropriation and repackaging of India’s musical heritage in order to sell it back to its originators for profit (not to mention some modern-day hepcat from the Pacific northwest planting his flag in what amounts to a record-collector-geek El Dorado) triggers uncomfortable connotations of colonialism.

Gramophone Repairer’s Requisites, from Suresh Chandvankar collection, Bombay. But then, without that imperial intervention we wouldn’t have these recordings. Which is what it’s really all about. Lovely and intriguing as Millis’ photos are, they essentially form a poetic, nostalgia-drenched, sweetly fetishistic backdrop against which the electrifying vitality of the music stands out in greater relief. The 46 selections dating from 1903 to 1949 run the gamut from Koranic recitations to proto-Bollywood theater music, from intricate mathematical constructions to heart-wrenching vocal acrobatics, from rigorous formalities to improvisational revelations.

For my money, the instrumental pieces are the most phenomenal, beginning right out of the gate with a mind-melting rave-up on the vichitra veena (a fretless slide stringed instrument) by the legendary Abdul Aziz Khan, followed immediately by a 1907 solo on jalatharangam—a set of ceramic bowls tuned by filling them with different amounts of water—over what sounds like a harmonium drone. There are devotional songs performed by devadasis (temple dancing girls), a raga played on kazoo, a comedy routine, a rare 1916 recording of a snake charmer’s flute, and a selection of vocal imitations helpfully entitled Sky Lark Squirrel Country Oil Mill Red Bird.

It’s thanks to Millis’ bona fides as a sound artist (as opposed to an academic ethnomusicologist) that this selection has such breadth, depth and idiosyncrasy. There are repeated instances of exquisite timbral subtleties that seem to be collisions of the actual music, the limitations of the recording technology, and the century of entropy that has left sedimentary layers of crackle and hiss—synthesizing to deliver an experience Millis once described as “tuning into a radio station from 10,000 years ago or from a distant universe.” The miracle is that in spite of the displacement in time and space, in spite of the distortion, the genius still comes through loud and clear.

Robert Millis

Indian Talking Machine: 78 RPM Record and Gramophone Collecting on the Sub-Continent

2CD/BOOK

22 by 17 cm; clothbound

244 pages

Sublime Frequencies, USA -

DECODER

So I was at this opening—or maybe it was an event. In a project space. Or maybe it was a party. There were paintings. It was definitely not an installation. Or, okay: there were things installed in it and the whole space had been taken over and changed but it was not just an installation—because within it there were distinct works. I mean, the walls were graffitied, and the art was graffiti, and there were new walls that were clearly put up in order to be graffitied, but then also on the walls there were separate and distinct squares with what were definitely paintings. I mean I have an MFA and I am pretty sure I could call them separate paintings. Also then there was a performance—but it was later. There were some rappers. But there was a DJ the whole time. Also there was a video—but the video was separate from the performance, it was on a screen on its own in a different part of the room. Also there were some really big paintings which were kind of walls but I am pretty sure that whatever it was when it came down, then they wouldn’t really be separate things any more so they were maybe installation parts but not paintings even though they were bigger than the paintings, and like them.

You know what I mean?

This is a specific way of showing art that anyone who has spent any time around art in the last 20 years will recognize. Often (but not always) the artists are street artists and often (but not always) the spaces are scrappy alternative spaces. The show itself is neither a display of discrete works in a white showroom nor full-on installation art with each piece fully subjugated to a whole walkthrough experience. The space is besieged, but transformed unevenly and not seamlessly, and is above all attacked not so much by a specific tool but by a sensibility.

The apparent simplicity of an omnivorous artist’s drive to turn a room into a sketchbook conceals complexities in this still unnamed medium or meta-medium. It references the way a piece of street art interacts with its street—the work needs an indeterminate amount of not-the-work around it in order to work. Unless it’s experienced as a photo, the viewer decides how much of the surrounding city scene is vital context and how much is just a fire escape near the art.

Installation at LAST Projects gallery by Xara Thustra, “Queer, Trans, Spaces,” photo by Ilona Berger. The show/installation/party/event/space-siege piles layers onto this relationship: you can decide the painting or sculpture on the wall is the art, you can decide these pieces plus the (less painted, but still painted) wall they’re together in front of is the art, you can decide the room is the art, you can decide the event is the art or you can decide that moment in time with all that happening is the art (and any other visit to that space is just looking at a corpse). More divisively: if you want to evaluate it (as buyer, as critic), you have to make this decision. How much of it do you wall off as “not the main thing” or “presentation?” How much of this do you want? Do you want to blame the artist for the parts you don’t want?

There’s an optimistic and interactive reading of this interpretive interaction, but there’s also an element of theater. Actual street art defies a purely functional reading of an everyday space: someone is paying for that property to do a specific thing, and the people walking past are expecting that thing—and the art is repurposing it. All good street art takes for granted its status as counter-programming, both visually and thematically—something to be discovered—the same way a book takes an undistracted and seated reader as a premise. Translated to a gallery, though—you can’t vandalize your own show. The viewer wouldn’t even be in the room if they didn’t expect to see the art—so the art is defying at least one less expectation than it was when it was outside, and is surprising in one less way.

This may be why these kinds of shows always spill so easily into happenings: on the street, the art is disrupting the street’s claim to be just a street, the gallery performance disrupts the art show’s claim to just be an art show, making it into a set, a backdrop—and then the party disrupts the performance’s clean claim to begin, go as planned, and end. The artists intuit that if something isn’t genuinely disrupted—or at least put in motion against something else, the gestures that worked outside won’t work anymore. The fact that the viewer has to actively choose to stop looking at the loud moving thing and start looking at the thing on the wall isn’t a bug—it’s an essential feature.

Image courtesy LAST Projects gallery in Los Angeles, http://lastprojects.org

-

PUBLIC DISPLAY

Where cities are being built up and money spent, local legislation has often passed a percent-for-art program; alternately, cities look to create stable partnerships between the public and private sectors, so some of that money is made available for public art, too. In the past, this has meant producing somewhat conventional monuments and commemorative images. Since the 1980s, public art programs have been better administered and present a much more contemporary image of the art world. The general rap: new public art is often quite amazing. Relatively recent high profile additions to the LA area include the following sweet spots.

1. Alison Saar, Embodied, 2015

The Hall of Justice

211 West Temple Street

Los Angeles, CA 90012

Saar’s monumental figurative bronze sculpture representing the spirit of Justice stands guard outside the Hall’s garden in all her composite ethnic splendor.

2. Peter Shelton, Sixbeaststwomonkeys, 2009

Los Angeles Police Administration Building

100 West 1st Street, LA 90012

The six plinth-mounted bulky, lumbering, volumetric bronze ‘beasts’ vaguely conjure up simian-like and elephantine vestiges as they silently hold vigil outside the headquarter’s entrance.

3. See Change, 2012

Thomas Bradley International Terminal

Arrival Area

This 58-screen, 90-foot linear video permanent installation suspended from the ceiling in the TBIT arrival area features 28 site-specific artworks that add up to four hours of moving images from artists throughout the USA.

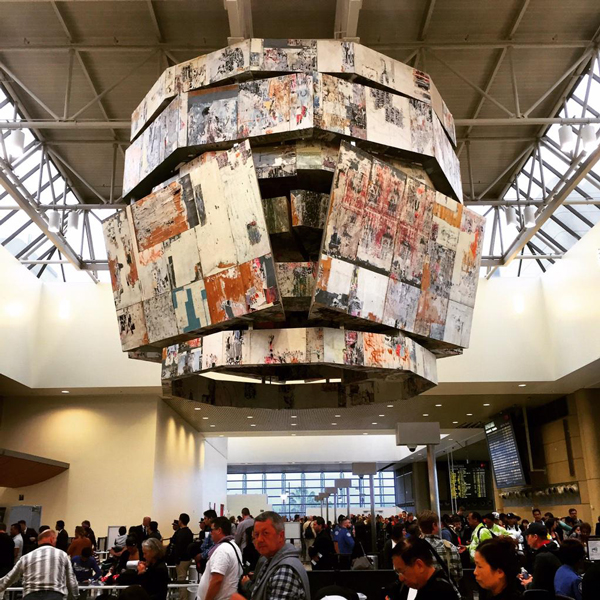

4. Mark Bradford, Bell Tower, 2015

Thomas Bradley International Terminal

Departure Hall

The massive suspended sculpture titled Bell Tower hovering above the passenger securitÔy screening area at TBIT mixes Bradford’s characteristic found wood panels and printed posters into a symbolic heraldic sentry.

5. Christine Ulke, El Aliso de Los Angeles, 2015

MTA/Division 13 Bus Maintenance and Operations Facility

corner of Cesar Chavez and Vignes

Historical collaging make up the highly detailed drawings trees that were transformed into a large grid of LED lit translucent panels turning the corner of this MTA Facility into an icon of transfigured nature by day and a lantern by night.

6. Hirokazu Kosaka, Buffer Zone, 2009

Little Tokyo/Arts District Station on the Gold Line

Station canopies that take the shape of three different Japanese archery bows, accompanied by Zen archery target benches replete with concentric circles of black and white, are all set into a platform paving design echoing Japanese tatami mats, collectively recalling how the perfect shot requires exact timing.

7. Susan Narduli, Timekeeper, 2014

231 S. De Lacey Ave. Pasadena

Four large-scale panels relay 40 hours of image loops about the issue of Time to passersby through animated elements, video, generative patterns and live feeds, conveying meanings that are both personal and societal.

8. Christine Nguyen, Oceanic Cosmic Whisper, 2012

Malibu Library, Malibu, CA 90265

Building up the images for Oceanic Cosmic Whisper ended up by crafting a water-swept dreamscape that take readers into a world where the real world of beaches and surreal world of the imagination converge.

9. Mara Lonner, San Angelo Landscape, 2015

San Angelo Park Community Center

245 San Angelo Avenue

La Puente, CA 91746

Deploying forms derived from vintage illustrations of native California and Mexican plantos, this new 2 and 3D landscape wends its way up and down the outside walls of the building, playing with forms, colors, light and shadow.

10. Chris Burden, Urban Light, 2008

The Wilshire entrance to LACMA entry plaza is inhabited by some 200-plus old fashioned cast-iron street lamps. Burden’s composition recalls a Classical Greek temple but more importantly and whether or not the lights are on, it has become a destination where anyone can count on making their rendezvous without the usually torturous LA directions. -

RETROSPECT

Kenny Price’s objects are modest in size and endless in meaning, which is another way of saying they make you think and feel instead of just impressing you. At a recent career survey at Parrasch Heijnen Gallery’s inaugural LA show, the first piece you are confronted with is a hard pod-like object with an unnaturally vibrant orange surface, titled Orange (1964). On closer inspection there appears to be a struggling wooden-like object within the object, either trying to escape or in the process of being swallowed up. The first thing I felt was that a fake machine world was demolishing the natural world. Suddenly the wood-like object becomes human and the oceans fill with plastic and this tiny little sculpture fills me with dread and sorrow because I can’t save a small piece of wood.

Ken Price, Silver, 1961, acrylic and lacquer on fired ceramic with artist’s wood base, 12 x 13.5 x 18″, courtesy Parrasch Heijnen Gallery. We have all heard the saying “less is more.” Obviously this does not apply to money or power, but in poetry an entire idea hides in a few words and in art one image can engulf the viewer. For me, small is somehow more fascinating than big. Big is merely impressive and when the idea does not deserve the space, you begin to ignore it for your own protection, which is what I do when faced with a gigantic balloon dog. Small, however—and I do not mean miniatures—demands that you climb down to its level.

So here we are at the next level. The adjacent sculpture, titled Silver (1961), looks like a lady’s handbag of polished steel and inside are strong steel bars from some prison, all curled up and forcing their way out. Of course, I think of my doctor father’s medical bag with all its instruments of death or the purse that my mother was forced to carry, which her virginity was constantly falling out of because that was her job way back in the ’50s.Don’t get me wrong, you might not feel these things but mysteriously you will feel something, because these objects have something to say if you listen. These small sculptures are made with such care and such passionate intent that you cannot help but let your imagination fly away before your brain can hit the delete button.

There are other pieces like the tiny epic landscapes that you could fit in your hand. You wonder how something so small can seem so big and then you realize that your imagination is turning them into the land of another planet— not Earth, but the inside of your head.I still remember the first Price I saw—a painting of a small cup on a table. I still wonder, who left it there? What used to be in it and why did I care? Was it about loss, leaving and loneliness? Will an excavator dig up this cup one day and remember me? Thank you Mr. Price.

-

CURFEW

Urban art is the great equalizer. With the rise of spray-painting and wheatpostering, the public is no longer forced to visit museums and see what rich white males call art. But one of the few mediums urban art cannot annex is sculpture; like museums, the field is dominated by the whims of the wealthy or the State: hideous office-park abstracts or courthouse Ten Commandment installations. Certainly there have been exceptions (Banksy’s pick-axed phone booth), but these are rare. And, unlike posters, sculptures are costly in both production and placement: as ephemeral as wheatposters, the sculptures are usually stolen or promptly removed. But the rise of cheap 3D printing opens the urban world beyond its walls and provides creative possibilities to a field that has become homogenized, and—as in the art world—boring.

Imagine if instead of Shepard Fairey spending the night plastering Andre The Giant Obey posters around LA (which is getting stale), Angelenos woke up to life-size Andre The Giant statues peppered around the city. Or suppose those untouched by the Syrian immigrant crisis were met, on their casual morning commutes, by thousands of refugees? Amsterdammers experienced just that—for the “Moving People” project, artists 3D-scanned 10 refugees from around the world, printed out thousands of 4-inch figurines, then scattered them throughout the Dutch capital.

3D-printed refugees, (father-son pair from Rwanda) sit on a wall in Amsterdam. The “Moving People” project alludes to 3D-printing’s other urban art potential: copy and pasting. Few outside of Amsterdam have heard of “People,” but what if the scans were made available for anyone to 3D-print, and the immigrants appeared, simultaneously, in every major city? Consider Japanese artist Megumi Igarashi. She was arrested for tweeting out a photo of a seaworthy kayak based on a 3D-imaging of her vagina, and was then re-arrested for her protest-response, arraigned on charges of distribution of “obscene data” after posting the code allowing anyone to print their own copy of her vagina kayak.