When I first read about Beatriz da Costa’s exhibition last year in Southern California, it sounded intense; I was intrigued and determined to see the show at the Laguna Art Museum. It featured da Costa’s most recent work drawing on the practice of engaging the personal, technological, environmental, and social—in this case, through the lens of breast cancer. An advanced stage of the disease took the artist’s life at the age of 38 in 2012. I had only recently been diagnosed with breast cancer myself and so, though we had never met and I was unfamiliar with her work, I felt a connection to the artist. It’s hard to think about creating art about something so difficult—something one would rather escape—and I was compelled by da Costa’s courage in making work so directly about her illness; it struck an additional chord since I was facing the same one.

Thinking about it, I realized some of my favorite artists used their own temporal and physical experiences as a subject in their work: Eva Hesse, David Wojnarowicz, and most poetically, Felix Gonzalez Torres. Indeed, one of the strongest exhibitions of 2012, “Alina Szapocznikow: Sculpture Undone,” which opened in the U.S. at the Hammer before traveling to MoMA, featured a powerful body of work by the Polish artist whose life was cut short by breast cancer in 1973 at the age of 47.

Szapocznikow’s intoxicating and highly material take on being in and of human form embraced a surprising range of new and traditional materials, including resin, cement, plaster, photographs, electronics and bronze. Her cast body parts—legs, lips, bellies, breasts—alone or fused with dewy wads of gauze, shimmering orbs of resin, extracted machine parts, or electric lights, are as powerfully playful, dark, moody and joyful, as the experience of life itself in its day-to-day iterations. But it is a later piece, the bulbous egg-shaped sculptures of Tumors Personified (1971) that expresses her experience of living with cancer, not only in its physicality but also in the complicated way these shapes seem to expand, each tied to a loosely held-together whole. Writing about the exhibition in The New York Times, Karen Rosenberg notes of Tumors Personified: “These wrinkled clumps of polyester resin, fiberglass, paper and gauze, some with Ms. Szapocznikow’s face on them, are alarming but gratifying for the viewer; they show Ms. Szapocznikow using art to define her illness so that it would not, in the end, define her.”

Is this what artists are doing when they make work about an illness? Or are they, we, continuing a process that comes naturally—to explore life as it is lived through art? I suppose it’s individual. In my experience, writing during cancer treatment was incredibly healing. I don’t know, yet, that any of these scrawled texts will transform into art—in the sense of being work that is shared and that communicates with others. But on a personal level, journaling and free-form poetry were powerful for me; they offered an outlet to express what I could not otherwise put into words. As an artist and writer, this could be an extension of my practice, but it didn’t feel that way; it felt—how can I put this?—necessary, vital, in the way that meditation and stillness felt vital, too, as a means of surfing complicated and inexplicable life-stuff. In the middle of the night, when I couldn’t sleep and my mind was racing, I would get out the little journal a friend gave to me at the start of treatment and just write.

At first, I also kept a log of poems on my laptop, but even this began to feel too organized, too much like “work” in the way that art (however fun it is to create) is work. We think about the audience and how the visuals or words will communicate and what they mean. I didn’t want to do any of that; I didn’t even want to use a tool (computer) that reminded me that these things existed. I just wanted to write without thinking; doing that was powerful and helped get me through some frightening times. Is this art, pre-art, or something else? Maybe there is a lesson embedded in this question—with all our conceptualization, investigation, and materiality, are we losing, or compromising, the power art has when it comes directly from a wordless place, a place of fear or uncertainty or desperation that can be brought on by cancer, certainly, but by life in general, when we are living and experiencing it fully? I don’t have the answer to this, but I think there is a space between unconscious emission and deep consideration that merits our attention.

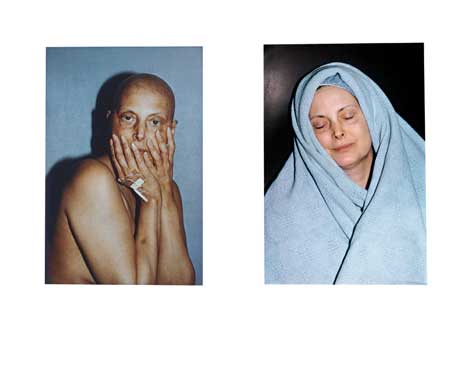

Hannah Wilke, Intra-Venus Series #4, July 26 and February 19, 1992, 1992–3, Performalist Self-Portrait with Donald Goddard, Courtesy Donald and Helen Goddard and Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York, NY

The work that Szapocnikow, Wilke, and da Costa made about cancer seems to derive its power from a position that is dually therapeutic and communicative—art and expression rolled into one intellectually and emotionally powerful package. This idea is evidenced in the work of Hannah Wilke, a conceptual artist who made profound work about her battle with cancer. Wilke began to create what has since become an influential body of feminist work around the same time that Szapocnikow died, and may have been influenced by the Polish artist’s experimental choices with material. Like Szapocnikow, Wilke was already exploring the body, more aptly the experience of being and body-ness, physically and culturally, before she was diagnosed with cancer. Her sculptures, performances, videos and photographs boldly addressed the psychosocial undertones of cultural norms of femaleness with courage and wit. The repetition and playfulness of her folded ceramic forms of the 1970s re-envisioned abstraction thorough female anatomy; their vulva-like shapes challenged both sculptural and social norms. For both artists, it seems that the decision to make work addressing the experience of cancer was a natural extension of their artistic trajectories.

From early in her career, Wilke used herself as model and muse for sculptures and photographs, a practice she continued after being diagnosed with lymphoma, for which she received extensive treatment before it took her life at age 53 in 1993. She used her own long brown hair, after it came out during chemotherapy, as material for the series “Brushstrokes” (1992) and revealed the full spectrum of her experience in the “Intra-Venus” photographic diptychs of the early ’90s. In “Intra-Venus #4” (1992–93), Wilke gazes at the camera, bald, with a catheter taped to her elegant fingers on one side; on the other, she is seen with eyes closed, head and shoulders draped in pale blue like a Madonna. The emotional punch of these works is palpable—it isn’t easy to see this beautiful artist’s nude figure stricken by disease and its treatment—but for those willing to look long enough, they are equally striking for the intensity of their spiritual and philosophical depth. Ironically, Wilke’s first one-woman exhibition took place in 1976 at the Fine Arts Gallery, University of California, Irvine, the same institution where da Costa became a professor of art in 2003.

It took me over a month, and the kindness of a friend and artist (who, I learned, was also a breast cancer survivor) to get to Laguna for the da Costa exhibition. I wanted to see the exhibition but had put it off in small part due to the fact that I thought it would be emotionally challenging, and in large part because I had been relatively incapacitated by the rigors of treatment. By the time I went to the show, I had learned more about my illness. Compared with Szapocnikow, Wilke, and da Costa, mine seemed to be a fortunate situation; like a majority of women with breast cancer today, it looked like I would be fine after many months of treatment. Though caught before it had spread in any obvious way, the type I had still required surgery, chemotherapy, and 30 days of radiation. On the day we went to see the show, I was midway through my long, hot chemo-summer; I was bald and fatigued and looking forward to spending the day with a friend at a show by the beach.

When we arrived at Laguna Art Musuem, we headed downstairs for “Ex-Pose: Beatriz da Costa.” The first room features elements from da Costa’s The Anti-Cancer Survival Kit (2012), including a database of research, computer games, instructions for a DIY garden, and other resources for caregivers and those with cancer. This work is squarely in line with da Costa’s conceptual interests in the economics of food production, channels of public information, and our relationship to technology but, despite its quirky, organic take on cancer treatment, is surprisingly pragmatic—almost dry—from the point of view of an artist facing the disease.

What struck me most in this section of the exhibition was a wall of colorful Post-it notes on which visitors had written the names of those they had lost. I wrote “Beatriz” on a pink Post-it and drew two little butterflies around her name before sticking it to the wall. I did this immediately upon entering the space, before realizing that this was not a piece in the show at all but rather the museum’s way of providing an outlet for viewers, as if creating the emotional space the exhibition’s topic embodied but the work itself seemed to skirt. Had I known more about da Costa at the time, I don’t know if I would have written her name (surely I wouldn’t have added the butterflies), but I was glad I did.

It was in the second and larger room of the exhibition, where da Costa’s three-channel video, Dying for the Other, is the only work on view, that the artist’s individual struggle was more profoundly revealed. A visceral and challenging piece, it pairs images of da Costa’s thin but strong body alternately attempting voice, yoga, and other exercises with those of laboratory mice used in many experiments (here, specifically, for breast cancer) and images of other patients undergoing treatment. Disturbing by nature, these pictures of pink and seemingly cryogenically frozen mice were almost too much for me, a vegetarian for more than 20 years currently undergoing treatments that likely originated with animals just like these.

In the gallery, I was too stunned to piece together how these difficult images could get viewers from a place of turning away to one of contemplating, as da Costa had hoped, “the ethics and politics of health.” Later, I considered what she wrote about, “the messiness embedded in the practice of maintaining one kind of life by killing another.” To me, Dying for the Other (2011–12) is a ritual act, a prayer to the animals that perish so that we may, ideally, heal and live. Intentionally or not, this triptych also seems to channel and expose the wordless flood of feelings and experience that bubbles up when faced with life’s deepest challenge. Da Costa’s is a conceptual piece moored by very real emotional, physical, and psychic experience that is as complicated and difficult and poetic as life—and as death.

To live and die is natural. We all do both, and illness is often part of the process. But to live with a life-threatening disease, even for a time, feels surreal; from a stronger connection to life and the body to the imposition of new limits and a host of strange and uncomfortable changes, it can be overwhelming. It might seem too simple a conclusion but, when our perspective is shaken, the abiding inter-connection between us all becomes radically apparent. Szapocnikow, Wilke, and da Costa each reveal it in different ways, by allowing us entry into their deeply human experiences of a fraught and fragile time empowered and memorialized by art.