The Los Angeles Free Music Society had its original heyday back in the 1970s, as much a dada and LSD-inspired piss-take on the high seriousness of experimental music—these were the days when Stockhausen was God—as a shaggy-dog extension of the Zappa/Beefheart/Wildman Fischer axis of dissonance that defined the fringes of “rock” music.

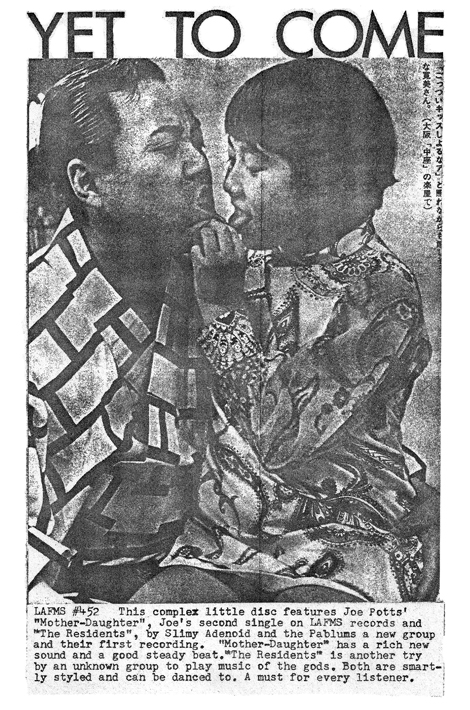

Coalescing around Pasadena’s legendary Poo-Bah record store, the LAFMS jammed, played out, issued cassettes and vinyl (in editions between 20 and 1,000, the average being 200), and published weird mail-art journals from 1974 to 1982, when they fell into a period of dormancy.

This hibernation ended with a bang in 1995 when Gary Todd’s Cortical Foundation/Organ of Corti label issued a staggering 10-disc retrospective box set of LAFMS archival material that was justly lauded by such international tastemakers as Thurston Moore and UK magazine The Wire. The LAFMS were hailed as pioneers of noise music (having allegedly jump-started the Japanese noise scene) and avant-garde deconstructionist turntablism (with the 1977 cassette Dennis Duck Goes Disco), but their collective range extended across the spectrum of experimental sound-making.

Since the “Lowest Form of Music” box set, the members of LAFMS have once again picked up steam, extruding reissued material and new product at regular intervals, and organizations like SASSAS and Nora Keyes & Don Bolles’ “Hush Club” have provided regular venues for their projects, while arts organizations like the Getty, REDCAT and Beyond Baroque have paid homage.

In 2010 their UK fans sponsored a three-day festival of performances, panel discussions and workshops, and in early 2012 Los Angeles gallery The Box inaugurated their new space with a LAFMS retrospective entitled “Beneath the Valley of the Lowest Form of Music,” which avoided the pitfalls of many archival institutional treatments of improvisational cultural moments by presenting a cluttered, anarchic installation of paper ephemera, actual artwork, invented musical instruments, and documentary materials supported by a battery of live performances (including one that was transformed into a wake for Mike Kelley, who had played with LAFMS band Extended Organ and contributed an installation to the exhibit shortly before taking his own life). The Box reiterated its support for the LAFMS this past July with another three-day series of concerts.

The latest and perhaps most unlikely exercise in LAFMS revivalism comes from EoB Books, the hard-copy publishing wing of the oddball online academic journal East of Borneo, shepherded by Tom Lawson and Stacey Allan at CalArts. Since 2010, EoB has offered an interestingly destabilized, populist version of academic scholarship by employing a limited wiki interface to amend art history according to a relatively non-hierarchical model.

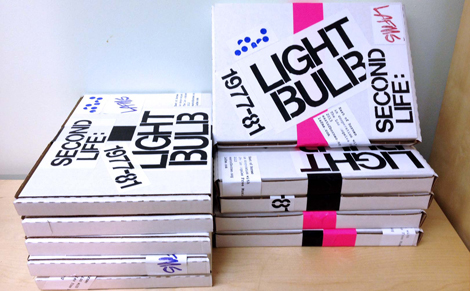

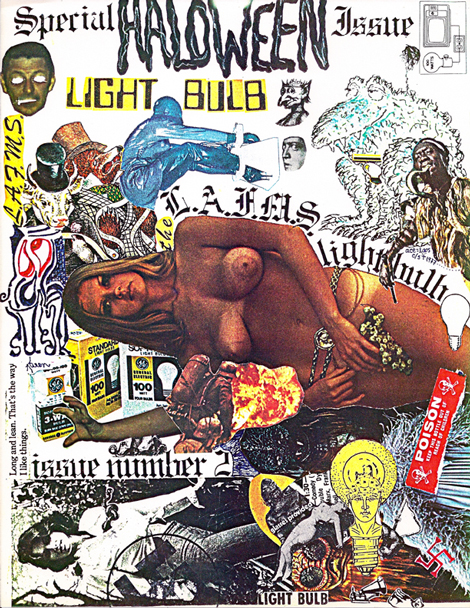

With Second Life: Light Bulb 1977–1981, EoB Books pays tribute to a predigital paradigm of non-hierarchical creative networking, the LAFMS’ pay-to-play house organ/artist zine edited by Chip Chapman. Comprising a run of just four issues—the last of which was a double cassette compilation—the original Light Bulb doesn’t exactly offer an overwhelming wealth of material from which to cull an anthology. Nevertheless, the resultant artifact—a “box set” of unbound photocopy sheets (mimicking the original format)—manages to be a time capsule of a particular moment in the LA underground as well as providing a broader cultural context of emergent DIY media in transition from the hippie paper/mail art subcultures to the initial explosion of punk zines.

Content-wise, the highlight is probably an extensive series of interviews—or questionnaires rather, since the subjects (mostly LAFMS members) are responding to identical sets of questions, including “What do you do?” “When do you do it?” and “What do you like to smell?”—of which the aforementioned Mr. Duck’s is the most sincere and voluble. The once and future Dream Syndicate drummer also offers at least one album review of another LAFMS recording—although with Light Bulb it’s not always clear who contributed what.

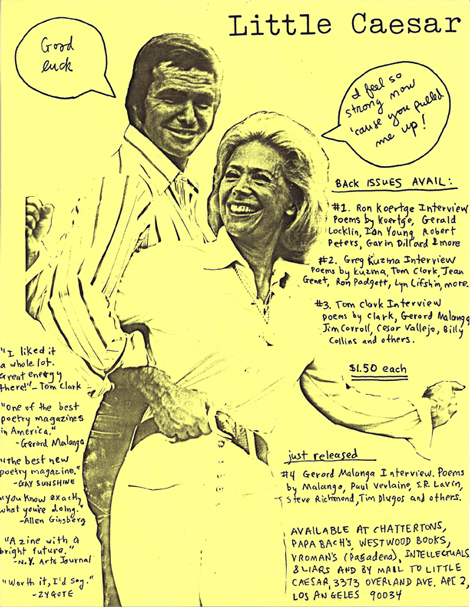

Which is the point, right? As long as you sent in $2 with your contribution, you were guaranteed a page and a copy of the final product. The bulk of the pages are made up of a hodge-podge of poems, prose fragments, rants, collages, artwork, and plugs for other zines and experimental musicians (Throbbing Gristle, Smegma, Half Japanese). Much of it is anonymous—the editor probably doesn’t even know who did what, although occasional familiar names crop up: a poem by Tosh Berman, The Screamers’ Tomata Du Plenty as one of the questionairies.

I’m not sure how much was left out—there’s what appears to be the annoyingly intriguing first page of an interview of Half Japanese by Dennis Duck—but the package could stand a little more retinality, and it would have made sense to include some form of audio (though the 1981 “Emergency Cassette” was reissued separately in conjunction with the show at The Box).

Quibbles aside, what Second Life: Light Bulb has to offer is not a pleasing aesthetic experience or nostalgic trip down memory lane—though it functions well enough in those departments—but an exemplary example of DIY cultural activity in its raw form, and free of the quotation marks that mar so many attempts to contextualize and update the insurgent improvisational subcultures of the past. Real creativity, like so many commodities, is always in the last place that you look.

Second Life: Light Bulb, 1977–81

Edited by Chip Chapman

Published by East of Borneo in cooperation with the (LAFMS)

62 pages + 4 stickers, looseleaf / 8.75 x 11.25 x 1 in., $35; eastofborneo.org/books/lightbulb