Of late, I have been selling various valuable paper collectibles online. First to go were the early punk flyers and fanzines. Now it’s time to part with a collection of Raymond Pettibon limited edition “art zines,” as they are sometimes called on eBay. Despite being depreciated by coffee stains, spilled by a girlfriend way back in the 1990s, they fetch prices in the low three-figure range. Not bad, but obviously nothing like the high five-figure range that his drawings often go for nowadays. Having just left the post office, where I had mailed a package of these comics to Italy, Pettibon was already on my mind as I proceeded to Regen Projects on something of a desentimentalized journey.

The vast expanse of open floor space and reverential gallery hush are a long way from Pettibon’s beginnings as artist-in-residence at SST records, responsible for Black Flag and Minutemen record sleeves and numerous scrappily Xeroxed zines. The drawings are still pinned on the walls but the quality of paper has improved.

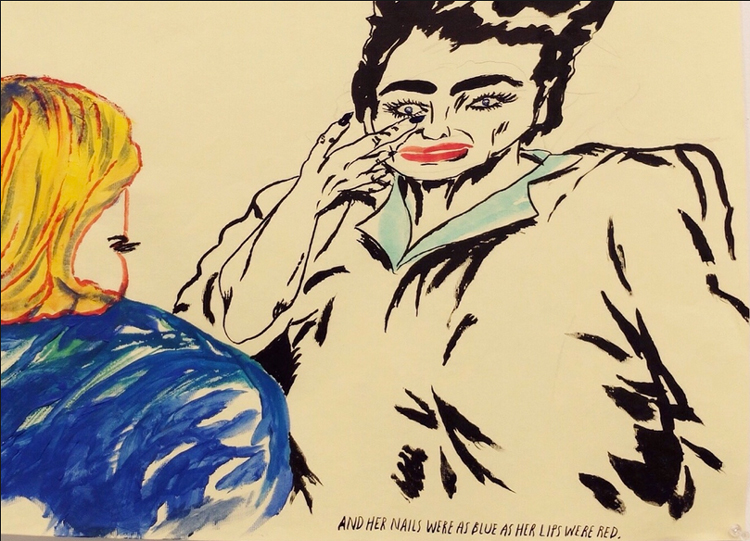

One cluster is dedicated to depictions of Joan Crawford, an old favorite, whose hard-eyes and monstrous blow-job mouth cast her as the quintessential embodiment of avarice and insatiable appetites. In these new drawings her features are distorted, as if from overfamiliarity, but she remains a hideous object of venal and venereal desire—“Her nails were as blue as her lips were red”—and, as opposed to the starkly declarative text of yore, reams of script overrun the images. The drawings haven’t changed much over the years, other than in scale, but the text has become progressively more meandering and allusive.

Pettibon’s skills as a draftsman have never been in question: they have always been dismissed. Crudely drawn—sometimes deliberately and necessarily crudely—dripping with ink as black as the sentiments expressed in the accompanying scrawl, he focuses on baseball, pornography, murder, suicide and other distinctly American pastimes—as well as those endemic to his native California: surfing, Manson, Hollywood. These subjects serve as vehicles for musings that fall just on the logical side of willful obscurity. Baseball players and cartoon characters plumb the darkest recesses of the psyche with pointedly indirect text that provokes and confounds while containing a sinister poetic beauty. Lucy stuffs her cartoon face with chocolates and states from a thought bubble, “I do not venture to print the expressions which I here mentally make use of,” a quote that can be traced to 19th-century art critic, John Ruskin.

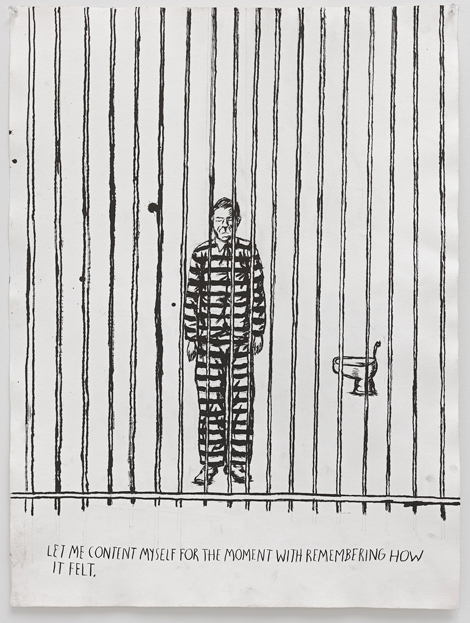

Raymond Pettibon, No Title (Let me content), 2015, © Raymond Pettibon, courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

Separating the unascribed quotes from Pettibon’s own dithyramblings can be an uneasy task. “Do you, my publisher, think it advisable to publish me, pressed between the covers of a book. I mean, to get myself known, read, as one who is buried alive” oozes Jamesian prolixity, and may or may not be attributable to the Master (It was not googlable). The trials and traps of the creative process are frequently addressed. Sophisticated language is combined with primitive imagery, and in his fusing of the visceral and the cerebral, Pettibon has something in common with some of his musical peers, particularly Mark E. Smith of the Fall.

The humor often consists in the contrast between the banality of the image and the seductive impenetrability of the textual ruminations. In one of the most conventionally pleasing pieces in this show a downcast convict in a horizontally-striped uniform stands behind vertical bars. Alone in a cell with nothing but a toilet bowl for company, he reflects: “Let me content myself for the moment with remembering how it felt,” perfectly capturing the morbidly wistful melancholy that is Pettibon’s special province.

His style is immediately identifiable; he dovetailed with punk but outgrew it, while losing none of his fearlessly sordid and macabre humor; he remains a solitary force and doesn’t appear to have had much influence on art-world trends. Some artists reveal truth and beauty, others truth and ugliness. Pettibon succeeds at doing what seems to be the duty of all contemporary artists, authors and especially comedians: to work with revulsion and fill us with an awareness of the grotesque absurdities of modern life.

There are some genuine laughs along the way. One drawing that could almost be New Yorker material features a ravaged male model in cowboy hat and underwear climbing a water tower with a cigarette between his lips: “The last of the Marlboro men is looking for a place to light up,” it reads. And one wonders how long it will be before The New Yorker embraces him. They embraced Crumb, why not Pettibon?

It took a good two hours to read all the text. It was worth it; and I left filled with a profound regret at having let go of all those art zines.

0 Comments