William Blake’s proverb “Eternity is in love with the productions of time” from The Marriage of Heaven and Hell is an apt lens through which to contemplate the paintings of Theodora Allen, both because her style and imagery suggest the visionary Romantic painter and poet, and because she is similarly concerned with temporality and mysticism.

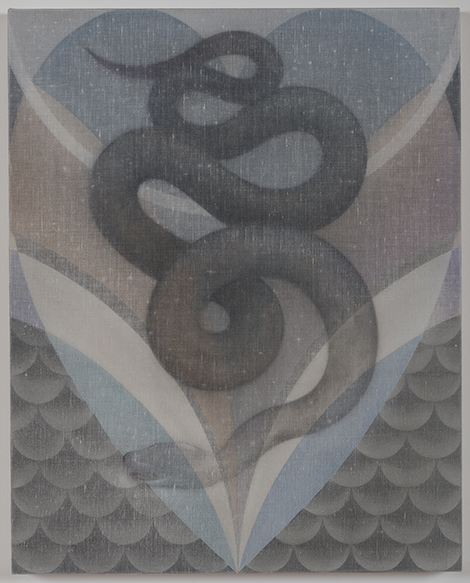

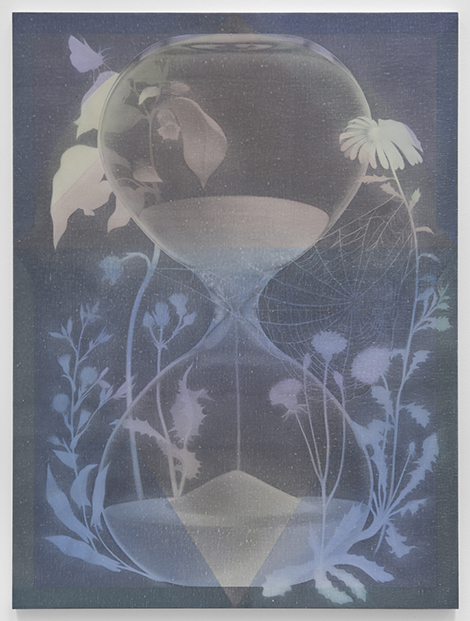

Allen’s paintings initially appear understated. Many are very small; all are done in light, ethereal washes of pale greens, blues and grays. The paint itself is unobtrusive, for Allen applies thin layers of oil paint and then immediately wipes them off using a soft cloth; the pigment seeps deep into the canvas and is more of a memory of paint rather than the conspicuous presence of it. Her subject matter is mostly found in nature and depicted within architectural spaces. Plot, No. 3 (2014) features raggedy weeds, dandelions, and moths curved into an arch, while Snake, No. 2 (2014) places the titular creature amid symmetrical geometric lines and shapes. Occasionally man-made objects appear, as in Plot, No. 4 (2014) where a stringless guitar rests both in a field of flora and fauna and in an internal frame of interlocking rectangles, and in Calendar, No. 2 (2015) in which an hourglass, festooned with cobwebs and flowers, dominates the picture plane. The only human being present in this garden of ghostly delights is a woman, whose lightly-limned face in Flash, No. 2 (2015) is turned in profile and has the exquisite, soft beauty of a Pre-Raphaelite subject.

Both the man-made and natural subject matter evoke the irreconcilable yet forever enmeshed notions of eternity and temporality. Moths are drawn toward fiery ends, flowers wilt, flames exhaust themselves, the grains of sand run out. Allen’s painting process itself evokes time, for each work had a beginning and an end, and the traces of each layer of paint and Allen’s erasure of them are visible on the surface. However, the artist seeks to move beyond fixed conceptions of time in her imagery and its evocations. The hourglass can be turned over infinitely, the guitar’s muteness will endure longer than any song, and Wildfire, No. 1’s curling flames are more ancient eternal fire than ephemeral blaze. The snake symbolizes rebirth and renewal in the shedding of its skin, and in its ouroboros form, infinity. The perfectly symmetrical architectural forms in which the creatures and objects reside allude to an inner vision, one that cannot be limited to or captured in temporal human experience.

Allen’s imagery and concerns are more similar to Blake than her contemporaries. Like Blake, Allen’s work insists on duality and opposition—we cannot contemplate eternity without the temporality of our existence, but can never fully grasp it. Allen’s paintings reveal an artist attempting to cleanse her own doors of perception to get as close as she can to the infinite.