I’ve been warned that Llyn Foulkes is preparing furiously for “Documenta 13” and as I get in touch to arrange a meeting, I’m wary, in part, due to his reputation for fractious soliloquies regarding fellow artists, critics, art magazines, and in general, the art world cliques that hold him at arm’s length. By his own account, Foulkes has been an outsider, a talented iconoclast shunned by the powers that anoint the grand artists of the day. Foulkes’ auto-scribed narrative is the continuous subtext for his meandering commentary on the art world, a surging tide of cynicism and discontent which is incongruously and entirely enmeshed with Foulkes’ innocence, and even naivety and idealism. These qualities mix in an uneasy boil beneath the surfaces of his eye-popping, sometimes disorienting tableaux, which are fueled by his encompassing world view and his obsession with politics, money, power, and his negotiation with culture in a broad sense. Foulkes’ work incorporates material derived from his personal life to the extent that figures and vignettes that loosely represent his lurking presence populate his paintings. He cannot help but put himself into his work. His vision reflects a deep suspicion of power and a sense of alienation: the individual alone, standing outside of society, editorializing on and defying the conventional wisdom.

Despite declaring himself the odd man out, this is Foulkes’ moment. Although he has shown regularly in Los Angeles since the early 1960s and has had many moments over the years, he has never been in the spotlight as much as he is now. His inclusion in the 2009 Hammer Museum show “Nine Lives: Visionary Artists From L.A.,” in his view, set him up for the Venice Biennale last year, and “Documenta 13” this year. And in 2013, Foulkes will have a retrospective at the Hammer Museum.

Llyn Foulkes, Installation view from Nine Lives: Visionary Artists from L.A., March 8 – May 31, 2009, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles. Photo: Joshua White.

When I meet with Foulkes at his studio, I find him engaging and charming. He is entirely open and hungry for conversation. Given his reputation, and our somewhat uneasy initial phone contact, I am a bit surprised. Embarking on a freewheeling discussion, we sit down at his workbench. “What do you want to see?” he asks. Then, “See this?” He directs my attention to a small construction on the wall behind me. It is about 4-x-4 foot by my estimation, and as I take it in, the image begins to register to me: A woman is curled up on a bed, cradling a shiny egg-shaped object. Foulkes’ double, his pictorial incarnation, sits in bed next to her reading the paper. The funky surfaces of fabric and carpet, and Foulkes’ manipulations of space play tricks on my eyes, and the whole thing seems to quiver. Foulkes started The Awakening when he began to feel his marriage was over, and it is a painting that enjoys legendary status. It is the same piece he pulled from a show at Patricia Faure Gallery in the mid-’90s after it was up for only a week because Foulkes said, “It wasn’t done.” This is what he has been laboring over for “Documenta 13,” the 18-year painting, or thereabouts, but now it is less than half its original size. Foulkes also showed The Awakening in “Nine Lives: Visionary Artists From L.A.” at the Hammer in 2009. In the exhibition essay, Hammer curator Ali Subotnick wrote that Foulkes felt pressure to capitalize on the success generated by his work in the 1992 MOCA exhibit, “Helter Skelter: LA Art in the 1990s.” He responded to the pressure by exhibiting a painting that wasn’t resolved.

Foulkes still isn’t done with the piece. He begins to explain some of the changes he has made recently, describing how each choice creates a cascading effect, before he finally gives up in resignation, saying, “All these decisions are being made very quickly, at the end. There was a thing here before,” he indicates a place on the painting, “and you know… ah, I don’t want to get into it.”

“This painting started at nine feet. It was nine feet.” Foulkes slows his voice, drawing out the word nine. “This painting is now just this big.” And he gestures with his hands to indicate the shrinkage. “I told Documenta I would finish it,” he laughs, somewhat ruefully, “and then I started changing everything.”

Up close, I notice the eyes are Phillips head screws; the flat surface reflects light. The tapered body of the screw recedes into the intricately formed eye sockets of the figures. The screw heads cast a small shadow and create remarkable depth. Reflecting on what I had read about this piece, I comment on what I expect are fictional elements in this narrative, and Foulkes answers without hesitation, “The whole thing is fiction.” Then he shifts immediately into a discussion about engineering the piece, talking about all the changes he still needs to make. “What I’ve been trying to do for a long time,” he continues, “is to make a really dimensional painting. You never see it done so much with anything that has figures in it; it is usually done in abstract. You take a shape and you say, ‘this is bending this way; I have to curve this, that way.’ And it keeps changing.” Foulkes wants very much to be done with it, to put it, and what it represents, behind him—yet he can’t seem to let it go.

Foulkes pours the kind of detailed craftsmanship into his work that some might consider the result of obsessive or stultifying perfectionism. He comments on the importance of keeping his hand in his work, saying, “I believe very much in process, because I believe that you really grow in process.” Rather than hiring assistants, he needs to contend with the work himself. “It’s easy to have somebody else make it for you,” he explains. “You change things, and things happen, and you discover things.”

Then, as though all the talk of changing his painting has made him tired, he declares, “But my machine, I don’t have to worry about that. You’ve seen the machine before?” I assure him that I have and recount the first time I saw him perform. We step into the “Church of Art,” the space adjacent to his studio where he performs. The machine, a self-contained hybrid instrument, a one-man band with drums, percussion, horns, and a bass guitar string that Foulkes plays with his feet, is lit with spots and amplified with microphones plugged into a PA system.

Foulkes tells me he’s packing the whole thing up and shipping it to Germany for “Documenta 13,” where he’ll be performing. He points out that although he’s driven it to San Francisco and all over Southern California in his van, he’s never shipped it anywhere, and that makes him nervous. “At first, I wanted to go on the cargo plane,” he says. “I wanted to be the escort so if it went down, I would go down with it. I could never recreate it!”

He has taken off his shoes and slid onto the seat, getting ready to play. I ask if the various horns and bells came from salvage yards. “They’ve been from salvage places, some were from Cost Plus.” He hits a bell lightly with his mallet and it rings with a warm sound that brightens up the space. We continue talking as Foulkes breaks into fragments of songs to expand on his answers. He seems lightened and relatively untroubled as he works the machine and sings. Clearly he enjoys this, and I wonder aloud if he feels free of his inner critic when he is playing. “I have an inner critical voice with the machine,” he responds, “it better be damn good. When it’s really rolling along, I feel every part of my body is in tune.”

Toward the end of our conversation I note that he has expressed disappointment in various interviews over the amount of recognition he has received. I ask how much is enough. It is rhetorical, and perhaps unfair, but I ask anyway. “How much is enough?” he repeats. “Yeah, I know,” he reflects, “I do have that problem. You see, it all comes from when I was a child.” He begins playing again, building into a song. “When I was a baby, my Daddy left me; he said, ‘I’m going down to California, with a banjo on my knee.’ So I made my daddies up – from the picture shows, from the face that grows from the picture shows…” Foulkes explains that as a child he felt the only way he would be loved was to be famous. “I’ve never gotten over it. As much as I try, I still haven’t gotten over it. So you say, ‘How much is enough?’ I don’t know.”

Coming soon: “Llyn Foulkes: A Retrospective,” February 3–May 19, 2013, at the Hammer Museum, for more info: hammer.ucla.edu

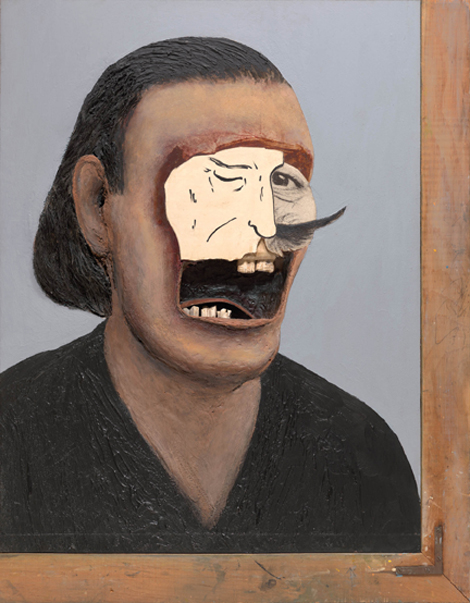

Below: Llyn Foulkes, The Lost

Frontier,1997–2005, courtesy Hammer Museum, Los Angeles.