Elizabeth Turk transforms huge blocks of marble into refined sculptures, pieces that display classical beauty and technical virtuosity. Observing the graceful artist at work in her studio in a Santa Ana marble yard—wearing ear protectors, safety glasses and padded cycling gloves, surrounded by dust and the ear-splitting sounds from the drilling of the stone—is to witness the magic of turning raw materials into delicate artworks.

Turk describes the months devoted to creating an individual piece, first carving the marble with electric grinders, then honing it with small files and dental tools. The resulting sculptures, resembling flowers, waves, lace, even wedding cakes, are held up as much by the gravity of the stone as by her sculpting, she explains. She calls her first major series of marble sculptures, “Wings,” with detailed feathered shapes. Her second series is “Collars,” resembling collars, described by one observer as “Elizabethan. Her third and most well-known series is “Ribbons & Pinwheels,” featuring sinuous filigree shapes. Her two decades creating these artworks helped win her a MacArthur genius grant in 2010 and a Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship (SARF) in 2011.

Turk talks about the dichotomy of her life before becoming an artist, about studying diligently and later working in an office, adding that she was always drawn to art. “When I finally decided to become an artist, my family was jumping up and down,” she says.

While growing up, Turk moved from Newport Beach to Albuquerque and finally to Boulder, Colorado. Finding herself in a new locale every few years, she spent hours alone looking at the natural and cultural surroundings; her early influences included the Huntington Library and Gardens in San Marino, California and Native American culture in Albuquerque. “In New Mexico, art was a part of everyday life, of the landscape, the way people lived, and the architecture.”

Turk attended Scripps College, Claremont, California, where she studied international relations. Yet a college study program in Europe helped give her a larger view of life, what she calls, “an understanding of the worldwide importance of art, and the evolution of human values through art.” While in Paris, she took an elective art history course at the Louvre and traveled to other European capitals to look at art.

After completing her studies, she moved to Washington D.C. to pursue a career in international relations. The Capitol, with its museums and especially the Corcoran Gallery’s art courses, became the influence that drove her to follow her muse. Within a few years, Turk had saved enough money to enroll full-time in the Rinehart School of Sculpture, Maryland Institute College of Art.

Shortly after receiving her MFA, she began exhibiting her bronze sculptures in the D.C. area. Fortuitously, an upcoming joint show with Louise Bourgeois, who was to exhibit, “a fantastic bronze spider,” compelled Turk to find a new medium. She chose marble, and found cast-off stone from the 19th century construction of the Lincoln Memorial. Her segue to marble started her journey exploring the material’s many possibilities. She began shaping the stone into works with delicate, fluid qualities.

Turk moved to New York City two decades ago where she reveled in the city’s museums and its larger visual art world. But after 9/11, she was drawn back to her roots, often visiting her parents in Newport Beach. She soon took up her own residence in Newport, while maintaining her New York apartment. Her peripatetic lifestyle, combining the best of the West and East Coasts, is her source of intellectual, philosophical and especially visual inspiration.

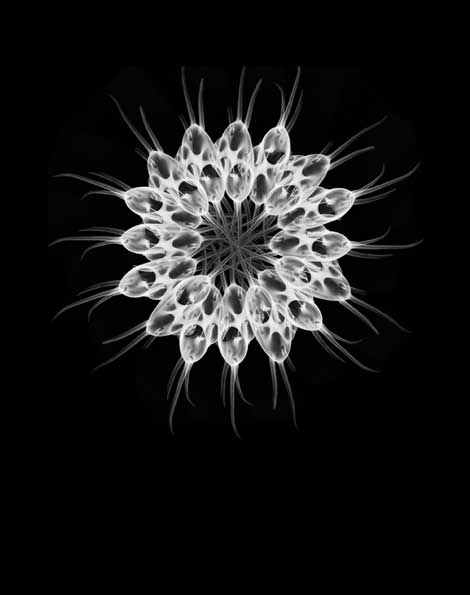

Throughout Turk’s artistic career, she has explored the complexities of nature, science and art, to understand, “the purest commonalities that link the past, present and future.” She created her most scientifically-oriented body of work, “X-Ray Mandalas,” during her SARF Fellowship. At the Smithsonian, she had access to the Natural History Museum’s large collection of shells (both marble and shells are composed of calcium). She photographed individual shells several times each, using special X-Ray equipment, discovering the specimens’ symmetricality and magnificent inner structures. She turned these images into LED-lit photographs. These 3D-like photos include Sunburst with its snail-like shape, Volute, like an eight-pointed star, and Wendletrap with delicate filigree features.

Turk returns to discussions of her passion for artistic creation and to the freedom it gives her, in spite of the intense physicality of drilling into marble. “Stone affords a timeless conversation. It will last longer than I will.” She adds, “I give new life to old materials. I reshape the stone, pushing its technical boundaries.”