I wasn’t even sure I would be admitted to the room where most of the performance took place. There was a small throng gathered in the courtyard. Another part of the audience was already assembling in the Billy Wilder Theatre, where the performance would be simultaneously streamed. There were monitors set up for the overflow crowd in the courtyard – convenient enough since I knew I wouldn’t be able to carry a beverage into either the theatre or the smaller annex auditorium. I was trying to get a quick cup of coffee before the performance began when the snap of a snare drum called me to attention. I hurried back to a bench near the theatre to make out two dancers costumed in white turban-headdresses that looked a bit like elaborate nun’s veils and what looked like white apron-skirt halter-dresses that left them exposed in the rear like hospital gowns moving sinuously, one of them seriously bangled and bespangled. The crowd swarmed around them which made them more difficult to see as they swirled and swooped into turns, snapping the crowd like a whip. We were by and large obedient.

I found myself at the end of the conga line, with no thought of actually gaining admittance to the inner sanctum (and that’s what it felt like), and settled back down on the bench. It appeared that last moment jitters had moved some of the audience to shift over to the Billy Wilder Theatre to watch it streamed, which left a bit of room available for a couple more bodies. One of the Hammer’s more thoughtful public programs people (and dynamic independent curator to boot – though he tends to fly under the radar) tipped me off to the extra space; and there I was.

Ron Athey’s performances have never been for the squeamish. But when you consider the guignol antics and bruising, mortifying, frequently bloody acrobatics to be observed (or sustained directly) in any number of private dungeons, S-M parties, and after-hours clubs, you sort of wonder what the big deal is.

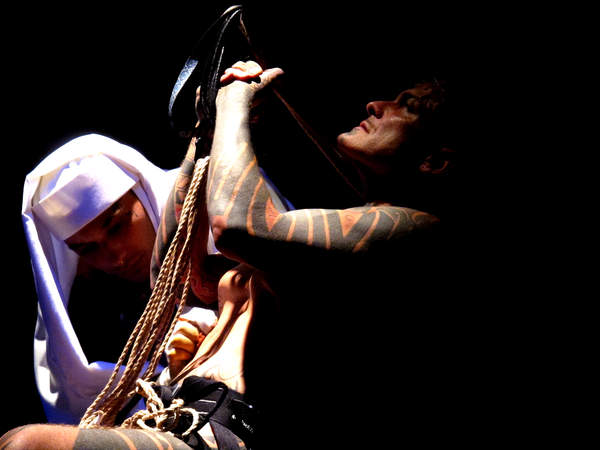

The view from inside was more or less the view on the screen, except palpably closer: Athey front and center and bound by a tracery of rope twined around his nude body to a wooden pier or stake. You’re in the room with the pain, the pierced flesh and penetrations and that’s the whole point. Although I would have been content to watch the proceedings streamed, there is something lost beyond the spatial and sculptural dimensions suppressed by a flat screen. Even if it were possible to present it as a hologram (or multiple holograms) projection, the sense of participation is key in these performances and that would still be missing.

Athey’s shaved head was already pierced with a number of long silver needles that looked like something between elongated acupuncture and knitting needles (a kind of tiara or wreath, more than a ‘crown of thorns’), and his silvery, crystalline eye make-up harmonized with this silvery spray, as it did with his similarly made-up and spangled acolytes. Closer to the action, I could see that the more heavily spangled of these two attendants was decked out not in glass spangles, but actual crystal pendants that hung in swags from piercings across his arms and body, turning him/her (I believe this was the legendary performer, Divinity P. Fudge) into a human chandelier. Alongside, a similarly tattooed and attired man stood at a laptop or keyboard orchestrating the soundtrack to the event – really a series of ascending, ever intensifying tones, that seemed to match the pitch (and pain endurance) of the performance (which actually more some resemblance to the soundtrack of the Derek Jarman film).

Yes, there will be blood – and sweat and tears and possibly other “rogue bodily fluids” (as Jennifer Schluesser’s feature in yesterday morning’s Times put it) – but they’re not for you. There is a kind of communion, even tran-substantiation, to put it in Roman Catholic doctrinal terms, going on here, but it’s really an exchange of energy, of imprinting (the press of hands upon Athey’s (already tattooed) flesh, the arrows and needles into it, the blood eventually pressed into white sheets). It’s also an exorcism – a call upon power by releasing power and invoking the power of witness, or physical presence to recover it; a cycle of charging, draining and recharging.

The mythology of Sebastian revolves around a subversion of state power – except that it was (and is) actually more of a direct challenge. (Certainly it was, at least according to legend, in Sebastian’s case.) Public shaming almost demands blood – not merely an obliteration of power, but humiliation, the mortification and eclipse of name and standing. The original 1994 Sebastiane was just such a challenge to state power and willful obliviousness in the face of the AIDS crisis and complementary right-wing hysteria over a host of LGBT issues and such canards as state support for artists working on the fringes (such as they were perceived at the time) of their respective media, practices and the industry as a whole. It’s ironic in retrospect to consider the froth that was whipped up around such artists as Karen Finley, John Fleck (whose cited work was in fact pure genius), whose work today seems almost mainstream, and for that matter, Ron Athey. Another irony was that 1994 may have been a turning point in the fight against the disease. But it had come at a steep cost – too little and too late for artists such as Derek Jarman, co-director of the 1976 film, Sebastiane (to which Athey paid homage in his original performance), who had died that year).

And yes, there was clearly more than a little pain, too – not all of which could have been planned or anticipated. As Divinity and her companion, thrust the arrows (still longer, heavier needles or lancets with tailed fletchings) systematically into Athey’s flesh, he let out a couple of howls that I’m sure were not rehearsed. At points, it appeared as if he was speaking in tongues – which, after a fashion, he might have been. Athey was reared in a strict pentacostal revivalist family; and although life and experience have put considerable distance between him and such religious beliefs, the spiritual sensibility in which he was immersed is clearly very much a part of his work and process. It’s almost hard to imagine his process as separate from this sensibility; it offers both a channel for the pain and a means of anaesthetizing it.

The aesthetic is something else again. It’s about that pain; it’s about the howl, the shriek; it’s about the fluids – or more precisely, the fluidity, the medium, the transmission – yes, the communion. There’s a tension here between the extent to which Athey initiates the audience into the sexual and occult hermeneutics of the performance and a straightforward demonstration – the action – the acting out (and up?) and upon body, sex, self, participants, audience, and (by implication) society.

I didn’t plan on staying for the post-performance chat that featured John Killacky, the former Walker Art Center director who in 1992 sponsored one of Athey’s most celebrated (or notorious) performances director of the Flynn Center for the Performing Arts of Burlington, Vermont. But I’m glad I did. Killacky’s skeletal history of events leading up to and surrounding Athey’s own career went on a bit too long, but at last Athey sat down with him and not a minute of their chat was wasted. Athey is that rare thing (easily observed watching his transfigured face at various points of the performance) – to mix movie metaphors, a savage messiah fallen to earth. He had some very smart things to say about his work and career, the state of performance art (and even celebrity performance art – which had some bearing on the subject of a panel I had just attended the evening before). But that will have to wait for another post.