Your cart is currently empty!

Stella Still Intriguing

Half or more of the best new work in the last few years has been neither painting nor sculpture.

—Donald Judd, Specific Objects 1965

When Donald Judd spoke of work that is a hybrid of painting and sculpture, one of the artists he was undoubtedly referring to was Frank Stella, who went on to forge a career based on this premise. For Stella, the sculptural quality of most of his paintings, beginning with the aluminum paintings in 1960, only the second series of mature works the artist produced, was his way of extending the parameters of abstract painting by moving away from its flatness. Stella was certainly not the first artist to do this; precedents for his painting/sculpture combination works can be seen in various European Modernists, such as El Lissitzky, Alexander Archipenko, artists from the Cobra group, and others. What makes Stella’s work unique is the way he has continued to expand the aesthetic of Abstract Expressionism through his three-dimensional paintings. In the documentary film Painters Painting (1970) he commented that New York School painting gave him the confidence to not worry about where he stood in relation to Matisse and Picasso, so he could worry instead about where he stood in relation to Pollock and Hoffman. His work takes certain assumptions in the work of those artists and carries them forward.

The Stella retrospective currently at the de Young Museum San Francisco is a rare opportunity to see his artistic evolution. Because he created paintings on such a consistently enormous scale, bringing even a modest number of his works together must have been a huge undertaking. Even so, the show seems small for a retrospective, including only 40 major works, and around 10 smaller ones. But considering the sizes they had to contend with (the largest work in the exhibition, Damascus Gate (Stretch Variation III) (1970) is 10 x 50 feet) the curators have assembled an impressive body of work. Viewers can carefully follow Stella’s development, which proceeds very logically from the earliest stripe paintings like East Broadway (1958) all the way to his recent work. The stripe paintings were, according to Stella, initially inspired by seeing the Jasper Johns’ Flag (1954-55), which is also where all of Johns’ mature work begins. So it would seem that one painting, inspired by a dream, launched the careers of two major artists.

There are two strong impressions one has after viewing the exhibition. One is the sheer drive the artist must possess to be able to produce such an enormous body of work composed almost entirely of mural size paintings. The other is the unevenness of the work; he seems to go alternately from the most brilliant and beautiful painting to a subsequent series that doesn’t seem to work at all. But that is only because he has such a willingness to explore new ideas in every body of work, and possesses a stylistic range far beyond most abstract painters.

The decorative quality in many of Stella’s paintings, particularly the protractor series from the late 1960s, has led many writers to compare him to Matisse, the master of color, but I see him more clearly linked to Picasso, the great maker of forms. The sheer variety and level of invention of forms in Stella’s work that he has maintained throughout his six decade career is nothing short of staggering. In regards to color, he actually seems to excel in the works that have little or no color, which are most prevalent at the beginning of his career and in the more recent work. This may be due more to the basic conflict between color and sculpture than to any shortcomings the artist may have as a colorist. In any event, he ultimately shows himself to be the consummate abstract painter, always taking risks, never resting on his laurels or repeating himself, always looking to push farther.

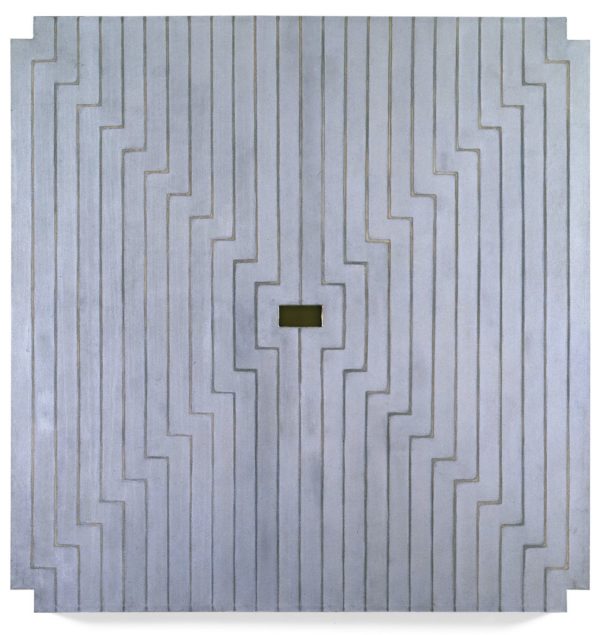

Certain periods of his work stand out as more successful. The austere, minimal black paintings from the late 1960s represent some of the best work he ever did, as well as some of the more radically shaped works from the early 1960s painted in aluminum and copper paint. These, his earliest shaped paintings, have the curious quality of looking more like an object than like a picture. This can be tremendously effective in an abstract painting, because as abstract as a rectangular non-objective work by say, Mondrian may be, it still looks like a picture of something. By creating flat paintings that look more like objects than pictures, Stella succeeded in making his paintings more abstract. These works vacillate between our perception of them as pictures or as objects, and alternatively as either flat or dimensional, and the result is hypnotic. These early works are also of historical importance, because they bridged the gap from Abstract Expressionism to Minimalism. However, Stella’s minimalist period was relatively short lived, and he soon moved in the opposite direction.

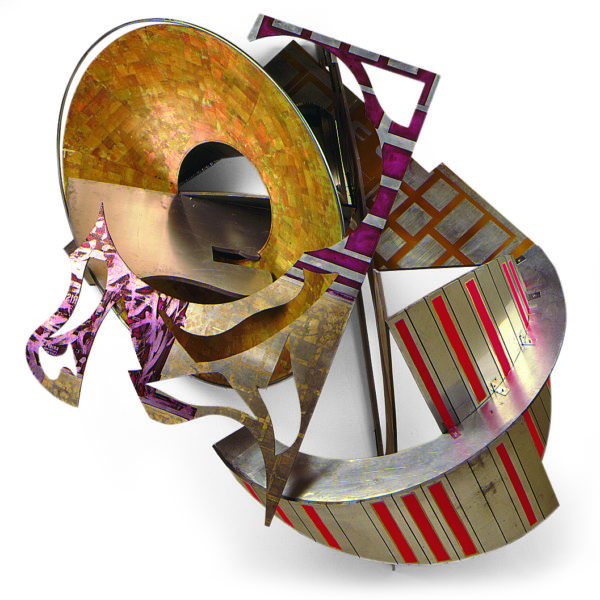

Stella’s work from the late 1960s and 70s is, with hindsight, the most problematic in his oeuvre. Some critics feel that the highly saturated color protractor series represents his best work, and although they are an obvious outgrowth of the previous shaped paintings, they have not held up as well. There are actually very few of these works in the exhibition, which is probably a good thing. Following that series the artist began to move increasingly in the direction of painted relief sculpture, initially with the collage works of the Polish Village series, and then to early painted reliefs made from sheets of honeycomb aluminum such as Talladega (1980) from the Indian Bird series—an orgy of writhing cut-out forms covered with pretty high-key colors and glitter. These works are difficult to take because the manic, frenetic paint application makes it hard to see the complex constructed forms, which are often quite intriguing. But by the mid-1980s, Stella had moved his painted reliefs out of the realm of the decorative and began to produce some of the most impressive paintings of his career. In St. Michael’s Counterguard (1984), which has been in the LACMA collection since it was created, forms spill aggressively out from the plane of the wall at least 10 feet into the room. The work is a riot of energy, possessing wildly inventive forms and ways to define space. Containing only a small amount of color, the piece is really more constructed sculpture than painting. Yet the fact that the artist continued to call this work painting makes it conceptually intriguing; just how three dimensional can you make a painting and still refer to it as a painting?

Stella continued to make wondrous, imaginative and innovative three dimensional painted works throughout the 1980s, mainly out of corrugated aluminum sheet and a wide variety of paint. Many of the works from this period are named after chapters in Melville’s Moby Dick, such as Loomings (1986), The Whiteness of the Whale (1987) and The Grand Armada (1989), one of the most compelling and memorable works in the show. This work in particular manages to quite successfully translate the best qualities in Abstract Expressionist painting into a much more three dimensional embodiment. Composed mainly of two large wave-like gestures mounted onto a somewhat geometric background, the piece has a number of smaller cut out shapes that combine with the larger gestures to create a sense of animated energy akin to that of Pollock and de Kooning. This concept of translating the idioms of New York School painting into a sculptural form was also shared by Judd, and was an essential aspect of his work; artists often create opportunities to break new ground by translating a known style into a different medium or discipline

During the last two decades, Stella’s work has continued to grow even more sculptural to the point that in an interview with painter Laura Owens published in the show’s catalog he states, “Well, we finally had to bite the bullet and call it sculpture.” While it is true that many of the more recent works follow the traditions of constructed sculpture that originated in Cubism and were defined by Russian Constuctivists like Vladimir Tatlin and Alexander Rodchenko, most of these remain attached to the wall, and some continue to use color as painters do. These hybrid painting/sculptures are the strongest work that Stella has done in recent years, surpassing his recent flat painted works such as the gargantuan Das Erdbeben in Chili (1999), one of the relatively un-sculptural “maximal” paintings. In the pursuit of breaking new ground in a genre, one must of course make it work formally, particularly in abstract painting; in this regard, some of Stella’s periods have been more auspicious than others. The most recent works in the show such as kandampat (2002), an unpainted wall sculpture that functions much like a drawing in space, and K.81 combo (K.37 and K.43) large size (2009), a painted sculpture that is attached on one or two points to the wall, continue to intrigue with their protean energy, inventive forms, and open-form aesthetics. Overall, one can’t but be impressed with the way Stella has continued to push abstract painting forward, always trying new formats, methods and materials. In an era where much of the abstract painting being made is designed to blend seamlessly with the interiors of modern and mid-century homes, it is gratifying to see the work of an artist who never compromises to suit taste, historical paradigms, or practicality.