Something kind of hit me today

I looked at you and wondered if you saw things my way

. . .

We’re taking it hard all the time

Why don’t we pass it by?

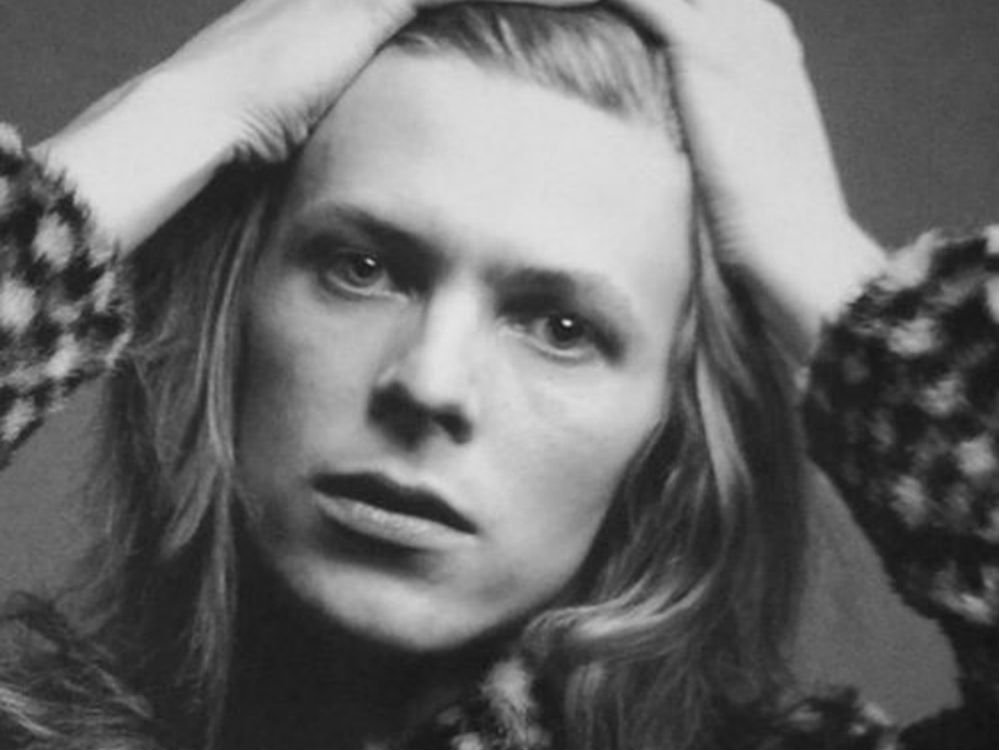

David Bowie, “We Are the Dead”

from Diamond Dogs, 1974

The first part of this post promised a superfecta; and I’m not sure it’s possible to live up to that, if for no other reason than simply the difficulty of making any kind of conclusive judgment on the kinds of shows I’m looking at in the space of a few hours spread out over 30 square miles. Sure, there are a few (e.g., the shows already covered in the first part of this post) – and even there, it would be absurd to say that my opinion might not be revised over repeated viewings. This is why we revisit shows in the first place. Or why we return frequently to favorite works in museums. Our first impressions are never our last; we bring something fresh to each viewing and take away something new.

Which is why I’ll be going back – not just to the shows I’m about to mention, but to the shows covered in (and some of those omitted from) the last post. I wanted to linger at George Legrady’s show at Edward Cella; and certainly his multi-layered, multi-faceted lenticular panels invited it; but couldn’t have spent more than 15 minutes with them. Memory is mined and manipulated in Legrady’s work, no less than Barnette’s, and far more explicitly. It also moves in both actual and remembered space and time for both the viewer and (presumably) the artist himself – which apparently related directly to the two-channel interactive animation piece Legrady is fascinated by the collage/montage of time and memory; the contemporary (or simply invented) foreground and (remembered or recovered) background of memory. The groundwork for the work was apparently laid with the discovery of a collection of family photographs taken mostly in eastern Europe (between Hungary, Romania and Transylvnia); and the lenticular work here apparently draws from photos of a Transylvanian picnic outing. You can see immediately how the lenticular work might lead to animation studies. The lenticular prints have their own quality of animation (albeit partially supplied by the viewer), but more important is the inherent fascination of the underlying photographic material and the overlaid imagery. I had to wonder how the animation would amplify that experience.

As I occasionally do in these instances, I had a look at the press release which set out Legrady’s aims more or less straightforwardly; also noting his “contributions to the computational arts,” which sounded like something more applicable to tax accounting – but maybe there’s a layer I’m missing.

It made for a striking transition to go from Chris Ballantyne’s show at Zevitas Marcus (next door to Edward Cella) that pursued a number of architectural and geometric themes and motives (and natural, too) to Toba Khedoori, whose past work has exploited both architectural and natural motives in her draughtsman-like explorations of existential and quasi-serialist geometries, at Regen Projects. Settting aside one striped painting that seemed almost literally a serialist work, it was quite different from what I expected. Here, only two paintings – seemingly tilted, eliding views of polished ceramic tiling more or less filling their respective canvases, one presented more frontally than its angled mate, bore distinct relation to that past work. Here, even meticulously rendered branches and leaves (in a completely white space) seemed well removed and on another plane completely from even previous naturalistic studies. Rather, the emphasis seemed to be a Fontana-esque contrast between the delineated plane and the absolute void – physicality and nullity.

From this kind of ‘naturalistic’ yet slightly ethereal art concrète, it was not much of a leap to the equally ethereal yet silken domain of Lita Albuquerque, at the Kohn Gallery. Albuquerque is well known for (frequently site-specific) work that bears on the body’s relationship to both the earth and cosmos; and surrounded by gold and silver discs in the main gallery, each inset within dense fields of rich, vibratile color that evoked both terrestrial and celestial qualities – purples both boreal and nebular, luminous sapphire blues that were both atmospheric and referenced the cosmic infinitude – the viewer felt suspended in a lunar ceremony. The jewel-like intensity of the color owes something to Japanese Enogu technique (or so the press release informed us – with the colors laid over layers of black and white); which may have something to do with the ceremonial aspect of the show. It was impossible not to be reminded of Japanese screen and silk painting.

: : :

That little ellipsis marks the approximate moment I broke off to surrender to the viral mischief that had besieged me. Part 1 went up without too many digital hitches – along with a nod to Bowie, whose funeral pall I was involuntarily sharing in body as well as spirit, as I succumbed to what felt like a not-so-mild bout of bubonic plague. That week-end was as notable sonically as it was visually; though, as with the George Legrady lenticulars, everything seemed strewn beneath leaves, branches, lakes and forest thickets. Even before the evening’s openings, I had the great fortune of hearing most of the Met broadcast of the closing performance of this season’s (David McVicar) production of Donizetti’s Anna Bolena – and possibly one of the greatest performances of the title role I’ve ever heard. In Sondra Radvanovsky’s performance, the dazzling vocal pyrotechnics (the role has an intimidating range from lowest to highest register) were matched by an incomparably supple and dramatically insightful handling of the role’s emotional complexity. Donizetti’s Bolena is every inch the queen she actually was, but also vulnerable and manifestly conflicted. Radvanovsky gave full scope to that emotional breadth and conflict in a dazzling coloratura performance that seemed to move inexorably from a high-strung regal poise to passion and indignation, from romance and resignation to tragic elegy – eclipsing possibly every other performance I’ve heard in the role, including Beverly Sills. She was well paired with her various foes and foils, including the incomparable Jamie Barton in the role of Giovanna (Jane Seymour), Ildar Abdrazakov as Enrico (Henry VIII) and Stephen Costello. There were so many great moments, I couldn’t begin to enumerate them all; but I will say Radvanovsky’s aria at the close of the first act (paralleling Abdrazakov’s responsive aria) was ineffably heart-rending.

I guess some people would say I was ready to get carried away on the first horse I mounted. But there’s really nothing quite as moving as the human voice. The following day, Emmanuel Ax brought an equally, agelessly supple technique back to Disney Hall for a performance of the Franck Symphonic Variations with the Los Angeles Philharmonic. (The Chopin C# minor nocturne he encored with wasn’t bad either.) The Pierre Boulez Mémoriale for flute and octet had actually been my selected ‘A’ side for the afternoon. Its timing – only days after Boulez’s death at 90 in Baden-Baden – was purely coincidental; but its original spirit made an appropriate memorial to its composer – and the soloist, Denis Bouriakov, and guest conductor Daniel Harding captured that spirit beautifully. Another uncanny coincidence was Harding’s expressive and slightly ‘contrapuntal’ conducting style – strikingly reminiscent of Boulez’s own distinctive ‘contrapuntal’ conducting style, though, unlike Boulez, Harding used a baton through all but the Mémoriale. Hard to say what Boulez would have made of the unbridled lyric romanticism of Schumann’s 2nd C major Symphony; but Harding and the Phil made something gorgeously soaring of it. The third movement C minor Adagio was possibly the most beautiful rendition of that movement I’ve ever heard.

Finally – Bowie…. [Continued Part 3]