Los Angeles was treated to some remarkable public conversations this fall. In early October The Broad conversations series presented a fascinating dialogue between artist Kara Walker and filmmaker Ava DuVernay. A few weeks later the Hammer Museum offered up a scintillating exchange between Connie Butler, chief curator at the Hammer, and Helen Molesworth, the newly arrived chief curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles.

The latter was both structured and spontaneous, instructive but relatively free of art-world vanity. And sometimes quite quite funny. Turns out that Butler and Molesworth have known each other for two decades—in fact, Molesworth credited her colleague with her first museum job. She had been in academia, and Butler recommended her to a headhunter for a museum position.

“Helen and I were formed intellectually at about the same moment in New York in the early 1990s,” Butler began, “and I think this has everything to do with how we do our work and the choices that we make.” Political movements deeply affected both of them. “It was a political moment in the art world —of AIDS, Act Up, and of WACK, and the now historically important Whitney Biennial of 1993.”

The two went on to discuss a few shows they had curated over the years.Molesworth said that all her shows “start with a problem.” And in “Work Ethic” at the Baltimore Museum of Art, she explored what kind of work is involved in different types of artwork. Especially poignant, I thought, was when she mentioned a time “when artists really and truly believed they were capable of changing the world—and in many ways they did, because they changed museums and they changed the culture of museums, and I think they changed curators, critics and art historians to think about art in new ways.” Butler brought up the landmark, if unwieldy, exhibition “WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution” that she organized for MOCA in 2007. Before leaving for New York’s MoMA, she had been curator at MOCA for 10 years.

It was refreshing to hear that both curators continuously self-examine what they do and how they do it. During the closing Q & A, one audience member asked Butler about charges that “Made in L. A.” was predominantly white. Butler gave an answer which reflected her mulling the issues. Her group shows, she said, have always considered diversity, and some of the charges in a Sesshu Foster article—the September article published on atomik aztex on wordpress—were “untrue.” That review starts off by saying, “It’s okay that the artists are all white, even the nonwhite artists (2?) are kind of white.” Rose Salseda’s much more thoughtful piece about the show at www.academia.edu/8569732/The_Myth_of_White_Art provides a rebuttal to that, although she doesn’t exonerate the curators from a certain white bias in selecting the artists. For the record, there were indeed more than two nonwhite artists in the show, and one of them, Jennifer Moon, won the $25,000 Audience Recognition Award. Also, neither writer mentioned Magdalena Suarez Frimkess—of Michael and Magdalena Frimkess, who work in ceramics and were featured prominently in “Made in L.A.” Suarez Frimkess was born and raised in Venezuela.

The conversation at the Writers Guild theater between Kara Walker and Ava DuVernay was equally engaging, perhaps in an even more personal way. Walker, who is collected by The Broad, spoke at length about her monumental and controversial installation “A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby” which was presented for two months at the former Domino Sugar Factory in Brooklyn through the auspices of the organization Creative Time.

Walker had never done a large-scale public art project before. When Creative Time approached her about doing one and took her to see the factory, she was seized by the challenge of using the whole space. “I felt like this was it, I didn’t know what I was going to do, but I knew this was the moment,” she admitted. “It was one of these moments you have to face your own ambition, or ego.” And Walker did fill the entire space, with a work people are still discussing.

The cavernous space was dominated by the 35-foot-tall figure of a black woman, naked and on her hands and knees, in a sphinx-like pose. Coated with 30 tons of crystalline sugar, she was a reference to the building and to the dark legacy of sugar cultivation and manufacturing in North America—think: canefields, plantations, slavery, factory work. Walker explained that “a subtlety” was a Medieval term for a sugar sculpture, and added, with a laugh, “Of course, the term ‘a subtlety’ is somewhat ironic.” Her interests lie in exploring contradictions, and the contradictions of power, she said, and “where do we possess it, where are we dispossessed of it.”

For me, the figure she created forced viewers to confront the mythic Madonna/Whore paradigm, as embodied in the pernicious stereotyping of black women. As Creative Time curator Nato Thompson has written, “She has the head of a kerchief-wearing black female, referencing the mythic caretaker of the domestic needs of white families, especially the raising and care of their children, but her body is a veritable caricature of the overly sexualized black woman, with prominent breasts, enormous buttocks, and protruding vulva that is quite visible from the back. If this evocation of both caregiver and sex object—complicated by her coating in white sugar—feels offensive, it is meant to.”

One of the most offensive aspects of the installation, however, were visitors taking photos of themselves acting up or inappropriately touching “Sugar Baby.” Walker initiated a documentary showing visitor behavior called An Audience. In her art practice, controversy is part and parcel of her longtime strategy—and race is still a hot and controversial topic in this country, especially in regards to African Americans because of the terrible history of slavery. Walker makes us face uncomfortable histories, the ones many would rather forget. She may be one of those artists who still believe that they can change the world, even if a little bit at a time.

In Memoriam

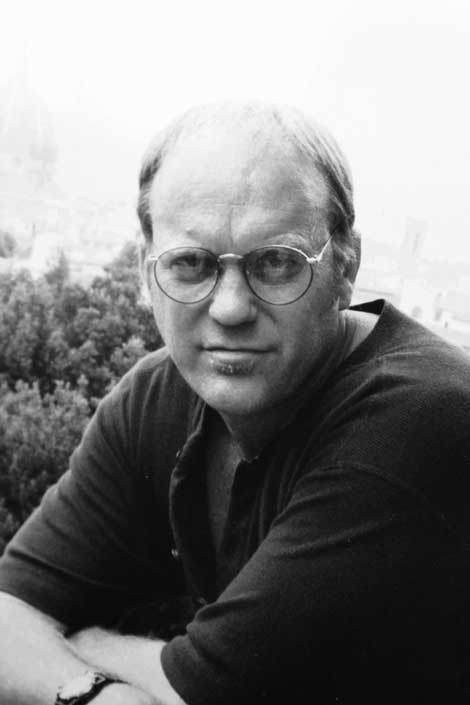

MICHAEL BARTON MILLER

(1949–2014)

Artist, humanist and professor Michael Barton Miller died on November 14, 2014, at his home in San Luis Obispo.

Michael was born on March 17, 1949, in Buffalo, New York, the second of seven siblings. He arrived in this world with the eyes, ears and hands of an artist—gifts that can appear daunting, to a young child, but that would steer the course of his life. Michael learned the concepts of justice, fairness and compassion at home, as most children do, but those concepts in this young artist’s mind became the foundation for his personal and artistic explorations.

Michael earned his first bachelor’s degree in Political Science from Arizona State University, then left for California, to join a film collective in Berkeley. While in northern California, Michael was commissioned to create several murals, including many at the Mendocino County Courthouse. He earned his second bachelor’s degree with Honors in 1986 from UC Irvine, followed by an MFA at the University of Southern California.

Over the last 25 years Miller taught at Pomona College, California State University, Long Beach and at several other institutions in the Los Angeles area. Michael relocated to San Luis Obispo in 1997 where he became a full-time professor at Cal Poly in the Department of Art and Design. He taught drawing, critical art practice and intermedia. One of Michael’s achievements at Cal Poly was the growth of a cultural exchange program with Silpakorn University in Bangkok, Thailand. He built relationships with many Thai artists, growing out of a friendship he established in the 1980s with Rikrit Tiravanija. Thailand had become a place where Michael met peers who melded their art and humanity into a kind of social impact that is seldom realized.

Michael’s art was exhibited in solo and group exhibitions at POST Gallery in Los Angeles, Los Angeles Center for Photographic Studies, The California Museum of Photography at UC Riverside, The Santa Barbara Contemporary Arts Forum, The Art Center at Silpakorn University, The Torrance Art Museum and Patricia Sweetow Gallery in San Francisco, as well as many other venues.

Michael had a way of touching people with his art, language, enthusiasm and love of the absurd. His insights were both tender and concise. Influences as diverse as poetry, history, critical theory, politics and social anthropology along with the practice of meditation informed his esthetic and ethic. His work explored connections between cultural practices, art and language.

Michael taught compassion and kindness because those were the lessons he learned from his spiritual teacher, Sant Ajaib Singh Ji, the man who introduced him to the practice of meditation and a way to find beauty when it appeared the most elusive. It was Sant Ji’s teachings that he found so meaningful and that he sought to infuse into his art work and teaching.

Michael learned of his brain cancer diagnosis on a trip to his beloved Thailand, a trip intended to be an exchange of art and scholarship. His first surgery was in a Thai hospital, where he experienced medicine as a blending of art and humanity. He spoke of his surgical team, the hospital staff and the University staff with the deepest love and admiration.

Michael is survived by his wife, Tera Galanti, daughter Mariah Miller and stepson Thomas Matzinger, along with his mother, Sarah Gehrandt, sisters Becky Friedlan and Sally Voita and brothers Ted Miller and David Miller. Michael is also survived by a generation of students who received his thoughtful guidance, as Michael strategically planted seeds of beauty and wonder.

—Mary Artino