In much the same way Chris Burden imbues his visual vernacular with his own brand of personal/social provocation, Sean Duffy, in his newest exhibition, aptly titled “Paintings,” at Susanne Vielmetter, shatters the expectation of the pristine sacred surface, electing instead to explode his images out of themselves and into the world. The manner in which these paintings were created alludes to violence without being violent. Despite the use of a gun to scar the surface of the canvas, Duffy’s paintings rely more steadfastly on the metaphor of action as a means of transformation and perhaps even redemption.

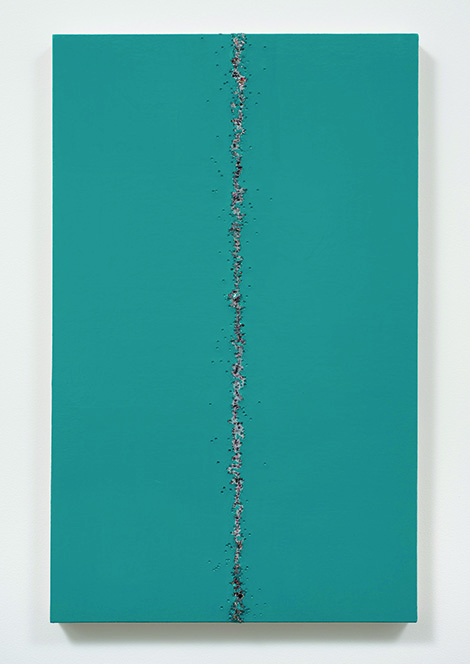

That Duffy’s paintings represent traces of human engagement, and the need for mark-making in whatever way that might occur, is undeniable. In Teared Up for example (all works 2014), Duffy bisects the singularly luminous peacock blue picture plane with a vertically incised line of BB gun shots, wherein the points of entry comprise a new order even as they destroy the calm tranquility of the canvas as a whole. Because we can so clearly delineate the space of the painted surface from the raw canvas beneath it, the work transforms beyond its own painterly aesthetic to become another kind of object altogether, one that requires our full attention.

Sean Duffy, “If You Can’t Beat ‘Em, Bite ‘Em, 2014. Courtesy of Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects; Photo credit: Robert Wedemeyer.

This is not altogether unfamiliar territory as artists like Lucio Fontana and Alberto Burri defined an entire generation through the act of negation, i.e. excavating the canvas to the point where parts of it shatter, burn and even disappear; like Fontana and Burri, and Burden too perhaps, Duffy also formulates the endless process by which an artist creates anything as simultaneously creative and destructive. Burden used firearms as a tool toward a kind of social interplay between artist and viewer. Duffy uses the gun to define, or even in some ways to defend his own existence in much the same way someone might carve their name into the trunk of an old tree.

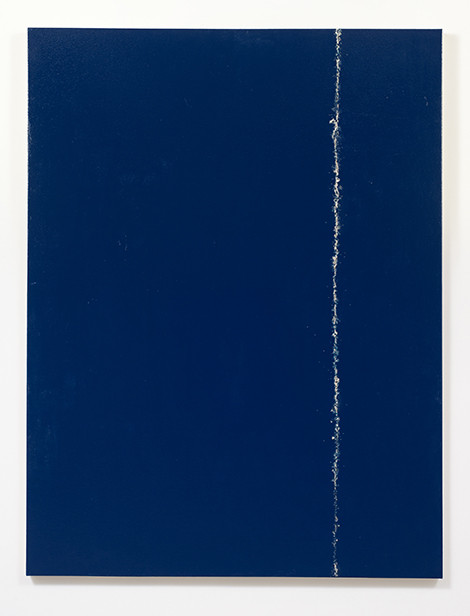

Sean Duffy, “Big Blue Tear”, 2014. Courtesy of Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects; Photo credit: Robert Wedemeyer.

Duffy presents us with two kinds of demarcation. In the first, color is used as an aggressive tool, the raw canvas seemingly torn apart by the force and intensity of the color itself, whereas with the second group of paintings, the calming colored surface of the canvas is acted upon by the force and velocity of the gunshots, which disrupt the color and expose the raw canvas beneath. Either way, the surface is despoiled and rebuilt. The other notable difference is the titling of the two different types of work. Raw canvas works have titles that refer to specific birds like Rufous and Western Scrub Jay. Rufous in particular reads like a roadmap for some dispossessed and raging hummingbird. Birds are quite antagonistic and highly territorial, and these paintings, which all use some sort of grid, seem to suggest a territorial mapping of space and time.

Duffy wants us as viewers to peer beyond the artifice and the glossy surface, to engage with the object itself, simultaneously blown apart yet strangely held together by the very thing that destroys it as in the magical Big Blue Tear where small BB pellets can be seen glistening under the harsh gallery lights, buried deep inside the incised wound of the canvas.