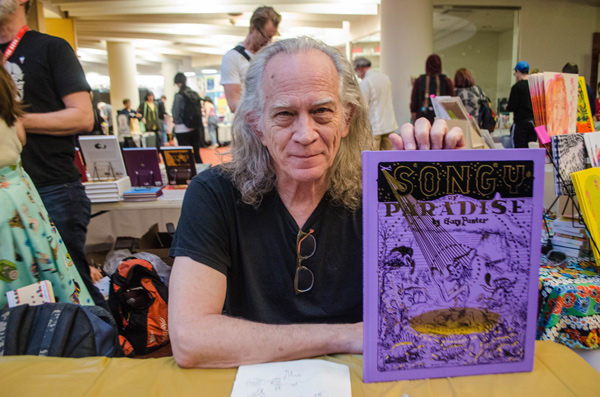

Gary Panter wears many hats—visionary punk cartoonist, Emmy-award winning designer for Pee-Wee’s Playhouse, psychedelic lightshow revivalist, cutting-edge graphic designer, experimental musician, candlestick maker. Having dazzled the comic art world with his elaborate and sumptuous freeform adaptations of Dante (2004’s Jimbo in Purgatory and 2006’s Jimbo’s Inferno), Panter has just released a final, tangential volume—Songy of Paradise, based on John Milton’s 1671 Paradise Regained.

DOUG HARVEY: Can you give a bit of a rundown on your upbringing and relationship to Christianity?

GARY PANTER: I was born in 1950 in Durant, Oklahoma. My father was [a member of the] Church of Christ which considers itself the only true church with a literal reading of the King James version of the Bible. We were lower class people who went to church three times a week and had Sunday school, Wednesday night bible class and singing. The church forbade imagery in worship, musical instruments in worship and orbit dancing and frolicking in general. I was a Christian missionary to Belfast in the summer of 1969—bringing Christ to the Irish religious war. Many things about it bothered me and it took a while to get over, if I did.

Do you consider yourself a Christian now?

I am not part of the cult of Jesus. And I am not a fan of organized religion. I am superstitious to an extent. I was raised to try to obey and conform with the end in mind of getting to a better place with the right ritual and magic words, which generally makes no sense. And also the idea that this place is a horrible torturous test seems ungrateful to the gift of some kind of existence—and not digging this one, why would you trust the god to give you an untricky one next? I just have to dig this one as much as possible and not seek THE ANSWER. Interesting questions are enough.

So, having spent so much time adapting Dante, why move on to the next biggest Christian cosmologist with Milton?

I felt like I had to do some kind of Paradise to finish the trilogy, but I built a lot of Dante’s paradise into Jimbo In Purgatory. I did reference lighting and motifs from Dante’s Paradise in this Milton comic as a background thing.

I got a research residency at the New York Public Library. I applied to study Milton and Paradise Regained specifically. It was an amazing situation to have access to manuscripts and an office to read books in. I didn’t know so much about Milton—and maybe I still don’t—but I got the idea from reading a lot of academic writing that Milton was a self-justifying religious pilgrim who found arguments for each change or shedding of skin on his spiritual journey, and he got in a lot of trouble.

What were you trying for formally in SoP? I notice that there are a lot of full-page layouts.

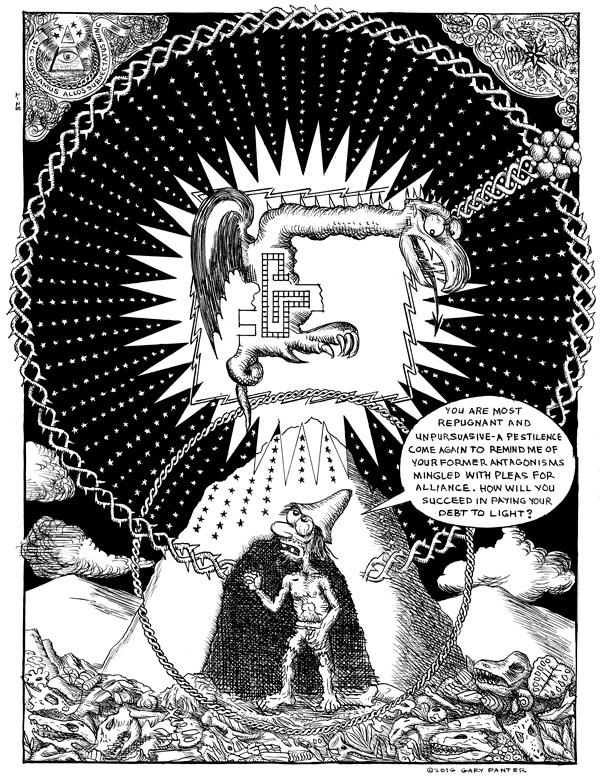

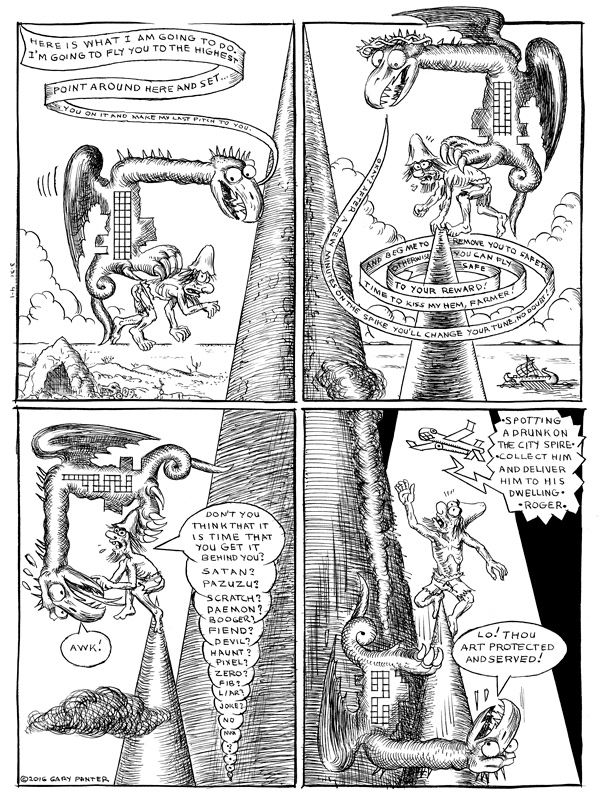

The further I went in the Milton story and in my Milton studies vs. the few verses in the Bible [covering the same story—Satan tempting Jesus in the desert with wealth, power and cheese logs], the less panels seemed required. The action is very limited and the text, aside from the moral teeter-totter quiz, is a show of what Milton knew— texts, places, scholars, kings, myths, and it was not interesting to try to draw everything he mentions.

Can you break down the technical aspects of your comic art in general, and SoP in particular?

I work with archaic simple tools. No computer. I use use dip nibs made by Deleter in Japan—the G series. I work on 3-ply Strathmore kid finish bristol drawing paper, though the paper today has more pores and is more problematic than in the past. Pelikan tusche is what I like to ink with—I sometimes leave the cap off to thicken the ink, but you can overdo that. Drawing with these tools makes the work look old-time. Maybe from the early 1800s.

I draw panel boxes with long narrow blunt-tipped striking brushes. The pencils are very tight, drawn and erased over and over and then trying to be better laying down the ink line. I try to never use wite-out and sometimes cut mistakes off the surface with a sharp blade. And I leave a lot of mistakes and try to not make them, but I am not a perfectionist. I want to get the idea across and go on to the next project.

A lot of literary comic art seems very much contained in the traditional textual literary culture. Would it be right to say that you see narrative, character, dialogue, etc., from more of a painter’s perspective?

A lot of the comics I have done are formalist procedural strategies that I am exploring or playing out, which sometimes makes for unreadable comics. So it’s good to also do comics like this one that also try to entertain while following some rules to produce them. Larry Poons used systems to arrange the dots on his early ’60s work—that made an impression on me. And also the ever-transforming work of Paolozzi and Fahlstrom. So those are models out of fine art for my comics.

Comics are different from paintings typically because they are trying to trap your attention for a while and take you on a little trip and maybe make some aphoristic point or joke. Painting is more of a shorter, arrested, indeterminate moment. A painting is a mood-influencing experience. The history of painting seeps in and the formalism of making and the abstract view and the processing of figuration if there is any, so painting doesn’t seem as linear to me. Though one can take strategies and apply them however you want.

And candle making

And what about Pee-Wee?

It was a childhood dream come true, but Hollywood is not my thing. I don’t want to make movies or TV, just handcrafts. Making a lot of candles for the past six months! I love making them.