I don’t remember when I first ran across Ad Reinhardt’s dazzling, sarcastic collage comics—probably in the ’80s (around the same time I stumbled upon his brilliant “Art is Art. Everything else is everything else” screeds, but before I saw his equally but oppositely amazing non-monochromatic “black paintings” at MOCA in 1991). Reinhardt’s cartoons are timeless classics, at least as far as art magazines go—perennially relevant probes into Modernism and its discontents, rendered in camera-ready graphic design gold—what’s not to like? All art students and most art world denizens could learn a thing or three from ole Ad.

What’s surprising is that—until now—their circulation in mass media formats has come in dribs and drabs, sometimes with years-long droughts between doses. Finally, in conjunction with last winter’s museum-worthy Reinhardt retrospective at David Zwirner gallery, these bitingly satirical yet earnestly didactic broadsides have been collected in a high quality hardcover book from the gallery and Hatje Cantz publishing.

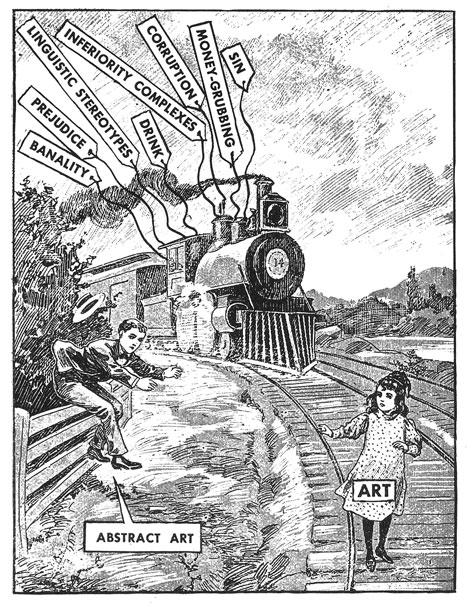

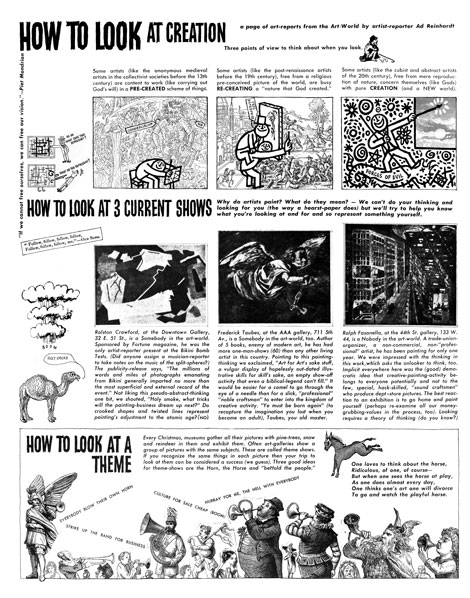

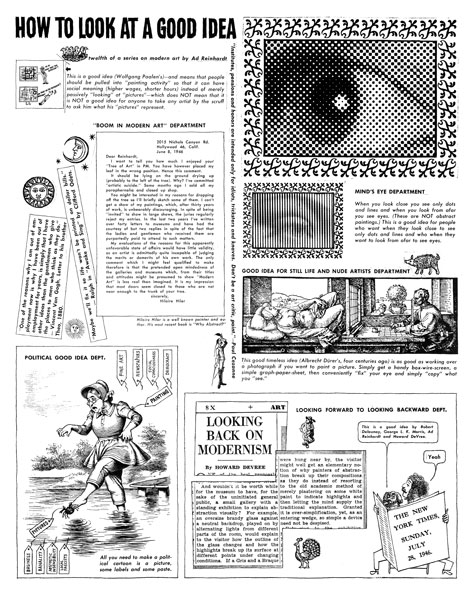

Created mostly between 1946 and 1954, Reinhardt’s cartoons are remarkable in both their form and content—often elegantly intertwined, since the subject matter never strays far from the vicissitudes of pictorialism. Picture-making, according to Reinhardt, was the reactionary nemesis of “Pure Art”—a position he reiterates tirelessly with cut-and-paste fragments of popular, scientific and art historical line illustrations spanning the entire history of visual culture, augmented by his own cheerfully loopy penmanship.

©2013 Estate of Ad Reinhardt/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London.

Using pictures to undermine the authority of pictures is typical of Reinhardt’s wry ambiguities. A contentious contrarian, his ceaseless bullshit-calling leaves no stone unturned, no heel unwounded, and no tenable ethical position in sight. In addition to his profound disdain for pictures, Reinhardt expresses constant contempt for commerce and criticism, and mocks virtually every contemporary artistic persona—from the self-mythologizing romantic heroicism of many of his AbEx colleagues to the pernicious “Artist as Freelance Prick-of-Conscience Busy Bee.”

Reinhardt’s ambivalence about cartooning as a medium—and it’s pretty clear that he considered it vastly insignificant compared to abstract painting—didn’t stop him from engaging his full creative intelligence in its deployment. With a solid background in paste-up and typography, and a familiarity with magazine publishing dating back to his college days as editor of The Columbia Jester, he fashioned his “How to Look” series with consummate professionalism, maintaining an entertaining populist edge across a range of topics that many still find intimidating to this day, and winning a broad audience through such outlets as ARTnews and the ’40s leftist daily paper P.M.

Anchored by this pragmatism, though, Reinhardt allowed himself extravagant flights of visual and literary fancy, indulging in ridiculous allegorical mashups and mind-bending wordplay, randomly devoting side panels to grids of “vibrating plate nodal forms” or chicken doodles by “social painter and ceramicist” Estaban Soriano. Constantly playing with the modernist grid and its complicity with the illusionistic depiction of space, one of Reinhardt’s favorite visual schticks involved stacking improbable, teetering totem poles of mixed signifiers—Corinthian pillars, mythological creatures, architectural fragments, tools, mathematical solids, corn cobs, monks, freaks and knights in shining armor; banners, placards and labels—along the vertical length of his page, as a sort of illuminated manuscript border.

©2013 Estate of Ad Reinhardt/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London.

Although his output was limited to a few dozen pages—much of it recycled, in true funny pages style—and in spite of his isolation from the commercial comics and cartoon industries, Ad Reinhardt deserves to be reassessed and celebrated in the context of graphic narrative as an autonomous art medium. In tone and visual inventiveness, his work brings to mind that of Will Elder and the other founding MAD artists, who were just gathering steam at the end of Reinhardt’s run. His West Coast art-world contemporary Jess had a less compartmentalized understanding of comics as an art medium, and his Tricky Cad collages (made entirely from scrambled episodes of Dick Tracy) are, strangely, more structuralist—and closer to the “Pure Art” that Reinhardt advocated in his polemics.

The “black paintings” or “last paintings” for which Reinhardt is best remembered are works that must be seen in person to be appreciated and understood. Subtle cruciform geometries unfold from what at first glance appear to be inert black monochromes. If any late Modernist work more emphatically embodies the “aura” that Walter Benjamin claimed was being siphoned off by the mass media, I ain’t seen it. That’s something. But another thing is the fact that Reinhardt’s “How to Look” collage comics are among the most masterful and prescient works of art created specifically for The Age of Mechanical Reproduction, and that irreconcilable difference is perhaps an even more revolutionary depth charge than the uppity semiotic manifestos he stooped to illustrate.

Ad Reinhardt | How to Look: Art Comics | Text by Robert Storr | Hatje Cantz/David Zwirner 2013