With June welcoming gay pride across the country, what better time to display and celebrate the range of LGBTQ, here called “queer,” arts in one of the largest cities in the U.S., Los Angeles. “Queer Biennial II: Yooth: Loss and Found”—whose title plays on the inventiveness and unruliness of youth (here, “yooth”), and how this yooth is engaged with loss (of an entire generation, aesthetics and sensibilities) and how they have found new ways to live and create in the world. This biennial is curated by the LA-based artist Ruben Esparza—along with an extended group of installation art, contemporary performances and film curators, as well as publishers and documentarians, such as Mark Cramer, Jon Vaz Gar, Brian Getnick, Jeremy Lucido, Tanya Rubbak, Marc Streit, Stuart Sandford, and Amy Von Harrington—focusing on national and international LGBTQ artists. Many of which take a closer look at the AIDS epidemic, which shifted artistic sensibilities and created a decidedly queer politics of aesthetics during the mid-1980s through the 1990s. This June also marks the 35th anniversary of the rise of the AIDS epidemic in America. With this in mind, the biennial examines how a younger generation has come to be influenced by the past—as well as by current and progressive political and creative practices. This exhibition shows the incredible vitality and range of a generation of LGBTQ artists to formulate new and provocative ways to represent the past, the body, gender and sexuality—as well as enactments of loss and mourning.

Upon entering the exhibition, one is thrown into a whirl of queer-eroticisms, provocations, youthful vigor, loss and despair, and hope because the past and the present collide—thus, making a rich and wild visualization of LGBTQ art here and now, also in dialogue with AIDS and LGBTQ history. Indeed, the range is phenomenal, comprising the LGBTQ multi-community’s sensibilities. I will focus on the opening night, which featured live performances. (It should be noted throughout the month of June there will be a series of performance art, film screenings, and academic lectures in various locations around Los Angeles; thus, expanding the biennial across the city.)

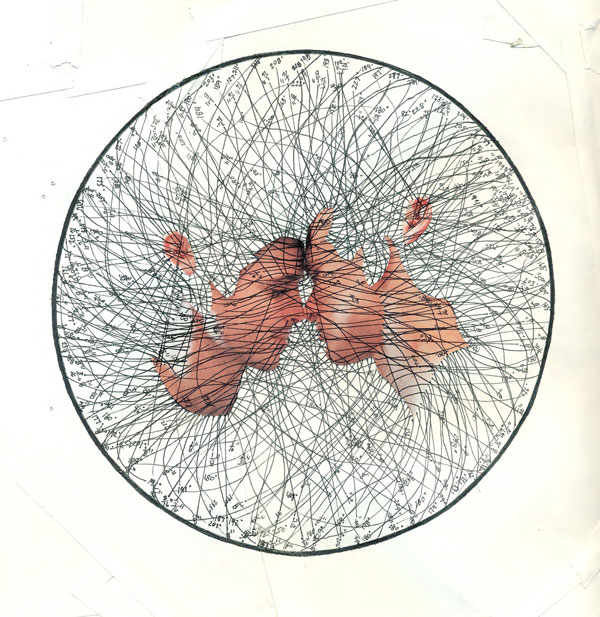

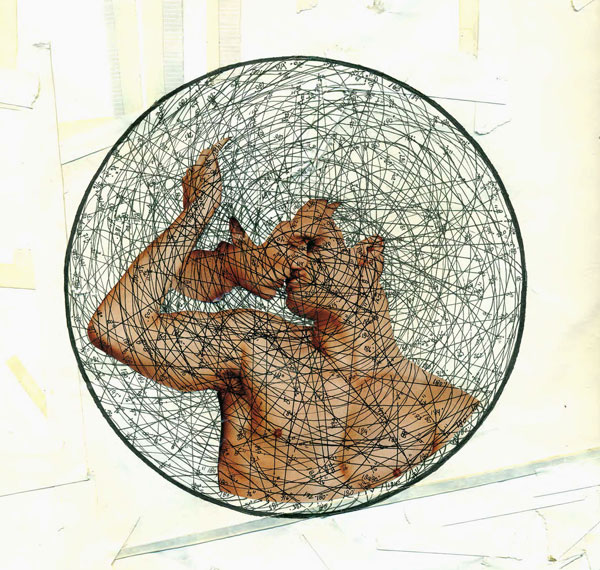

Enrique Castrejon’s mixed media works titled Anatomy of a Kiss (2016) and A Reconstructed Memory (2016) are methodological—yet emotional.

The two small circular collages, which consist of magazine cut outs, are measured in inches and calculated in angle degrees to a precise unit in an effort to “scientifically” investigate and question gay relationships, monogamy and ideal forms of companionship for gay men. This series of work was autobiographical, which arose from failed and lost relations. Ironically, Castrejon’s desire for scientific rationality gives way to the emotional.

It turns out the subject and experience of raw emotions and utter loss loops in and out of most of the exhibition. Loss is literally spelled out in a painting from 1993, by the Chicano-identified artist Joey Terrill, which reiterates, with a difference, the Love sculpture by Robert Indiana—he effectively queers it. Also, Ruben Esparza takes up the issue of loss (and youth) in this blood drawing, which is titled the same as the biennial, Yooth: Loss and Found (2016). This image is powerful in that it is the blood of a self-identified gay man, and such blood is still always already seen as infected; gay men still cannot donate blood. The whiteness that surrounds the blood letters function as a space that still separates the gay male body from normative society—not that such a space (or gap) is a “bad” thing.

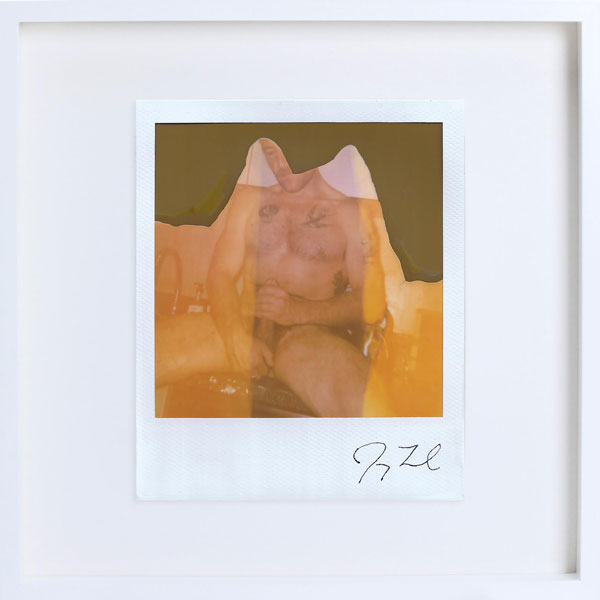

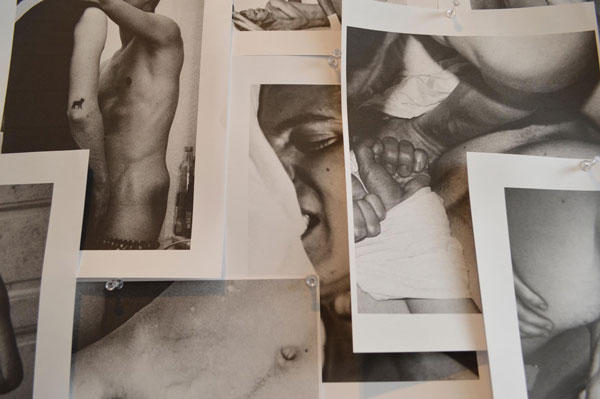

The work of Jeremy Lucido’s are “destroyed” Polaroids, which are titled Instant Portraits (2016). These are images of men posing erotically or jerking off; the men become anonymous by the deterioration of the medium, which erodes their faces. There is a certain fleeting nature to these images, highlighting our inevitable disappearance—our loss, our finitude. Also tied to loss, and related to the ephemeral, is an artwork by Matt Lambert and Jannis Bersner, which comes from their magazine Vitium (2016), who photographed the queer-erotic lives of Berlin youth.

Their photographs are photocopied and plastered haphazardly to the gallery wall; the very medium itself highlighting the ephemeral, non-archival and fleeting nature of the medium. Indeed, there is an embrace of the finite, the here and now, and the material world that is passing—but in a way that is not melancholic or nostalgic. Finally, Stuart Sandford shows a beautiful Polaroid, where a man’s crotch is covered by a baseball cap with “DEATH” written across it in gothic font.

To be sure, morbidity pervades the exhibition, which should not surprise us given that these young artists inherited the aftermath of the AIDS epidemic, but there is also a retrieval—again “loss and found.” An example of this new era we are in can be seen in the work on display by Boston Elements, and their mixed-media art, such as Protect Your Truth (2016), that highlights Truvada (an anti-HIV drug) as potentially allowing many LGBTQ people to begin to freely experiment sexually—like before AIDS.

Surfacing experimental sex, there are the campy and celebratory ceramics of Pansy Ass Ceramics. Homoerotic scenes are painted over vintage china, with a teacup series, all titled HIV Honors (2015), that pays tribute to some artists’ lives lost due to AIDS—such as Keith Haring and David Wojnarowicz.

On a brighter note, The Holes of Your Memory (2016), by artists Amy Von Harrington and Jaye Fischel, invites the audience to enfold themselves into the lips of a plush, fuzzy vagina, while the artists caress and comfort the participant.

Another uplifting piece, which Nicolas Bourriaud has termed “relational aesthetics,” is an on-going installation by Daniel Hellman titled Full Service. This relational work asks audience members, singularly and privately, to meet with the artist in order to have a wish fulfilled: ranging from telling a secret to licking one’s neck to, well, whatever ones wish may be. This work highlights a certain generosity and openness to help others.

Finally, Daphne Von Rey passed out white flowers that had been soaking up HIV infected water. This comments on the trials and tribulations of building a romantic relationship in a world still phobic of HIV+ people, but Von Rey has hope and invites the audience to take a flower—the symbol for peace and love.

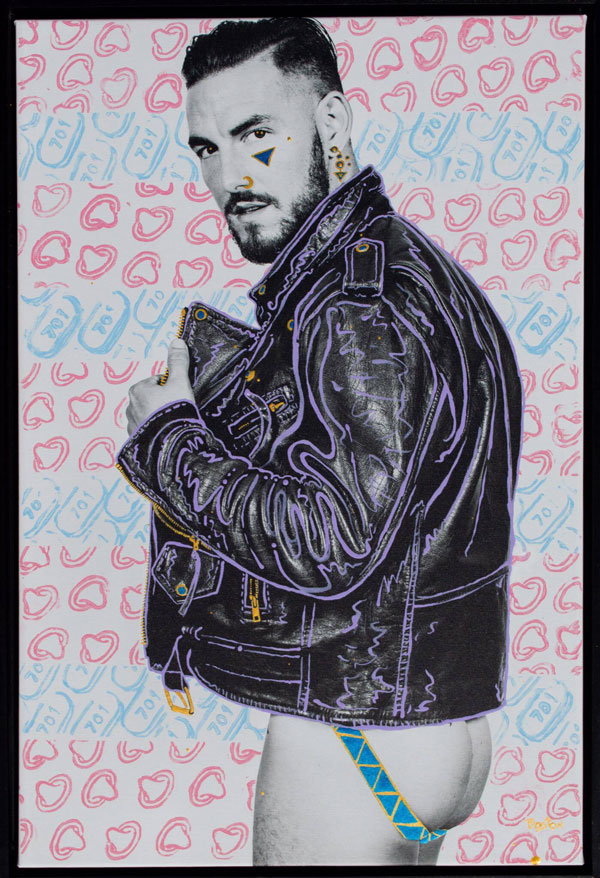

There were many other highlights, such as the queer-erotic paintings of Gio Black Peter and Naruki Kukita, the “penis photographs,” titled Dick (ca. 1980–2000), by the famous, gay 1980s painter who reckoned with loss and death: Ross Bleckner. There is also the wonderful Rafael Santiago photograph titled Mana Linn (2015).

This focuses on issues of transgenderism and queerness to create alternative aesthetics of living and presentations of the self.

This review can only touch the surface of this tremendous and generous exhibition, so to conclude I would like to reiterate that, in part, what “Queer Biennial II: Yooth: Loss and Found” does—much more than only presenting amazing artworks, as well as performances and screenings—is create a space for queer aesthetic subjects to perform and highlight their sensibilities. Through the curatorial work of a group of talented individuals, what is so often invisible is made visible, and what is so often missing in museums and galleries is surfaced: queer visualities—if not lives—are made manifest. In more ways than one, the curators enact what queer theorist Eve Sedgwick has said, “I think many adults (and I am among them) are trying, in our work, to keep faith with vividly remembered promises made to ourselves in childhood: promises to make invisible possibilities and desires visible; to make the tacit things explicit; to smuggle queer representation in where it must be smuggled and, with the relative freedom of adulthood, to challenge queer-eradicating impulses frontally where they are to be so challenged.”

The opening night—as well as every day of its showing—is a remembrance of the lives lost due to AIDS, but it is also a celebration that we queers are, and will continue to be, here. This exhibition, the surrounding events and performances, and the lives of the artists make this all very true—and very hard to elide or erase.

Author’s Note: This review was written before the tragic event that took place in Orlando, Florida at the gay nightclub The Pulse on June 11, 2016. Today, I still feel a deep sadness—and I will for some time—at the horror that took place at an LGBT safe and celebratory space. I can only hope that exhibitions such as “Queer Biennial II” continue to happen—thus, displaying the power and variety of LGBTQ arts, by LGBTQ artists who have all experienced, in one way or another, death and disaster, loss and grief—as well as pride and jubilation. As a critic and art historian I have dedicated my life to spotlighting and researching LGBTQ art, as well as teaching art history from a queer perspective—and I will continue to do so because queer art, queer lives, and queer history will not be eradicated. —Robert Summers, PhD, Los Angeles

Queer Biennial II: Yooth: Loss and Found

June 4 to June 26, 2016 (Thursdays to Sundays 1:00 to 5:00, and by appointment.)

Industry Gallery, 801 E. 7th Street, #103, Los Angeles