Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia loves to create objects expressing hybridized meanings, calling attention to how things are not as simple as they first appear. For “by Deborah Calderwood,” his first solo exhibition at CB1 gallery in downtown Los Angeles, he presented paintings appropriated from his wife Deborah’s early childhood drawings, touching on notions of originality and love. For “Papel tejido,” his second solo show, he wove blanket-like forms emblazoned with crosses and steeples from painted paper strips, mingling textile traditions while frustrating the anti-image modernist grid. Hurtado Segovia is currently using those lacing techniques to create embellished pillars and poles that connotatively explore archetypical symbols of faith and power. His formal propositions launch complex discussions about the meanings we invest in everyday objects and the shared histories that make up who we are. I recently sat down with Lorenzo in his home/studio in Tarzana to discuss his past projects and his recent work.

Artillery: In keeping with the theme of this issue, what are your thoughts about Mexican and American identity in relation to your work?

LHS: My upbringing was first solidly in Juarez, then a border experience, then LA. Now I’m a naturalized U.S. citizen through an amnesty process initiated by family members who dug out my grandma’s birth certificate from California. I’ve been in LA for 11 years. I have a lot of thoughts and emotions shaped by my Mexican psyche. But my day-to-day reality is informed by the United States, by U.S. politics and Chicano politics more specifically, especially with California’s anti-immigrant history, prop 187 and our proximity to Arizona.

[In] my work, a lot of things I see now have threads going back to my youth, especially the notion of being handy and making things. In Juarez everyone needed to know how to do things, put up a wall, mend sheets, fix things. I see this history informing what I do now.

I’m wondering how you see your formative years impacting your practice?

Well, when I was 8, my grandmother would take me to this craft store once a week. I would make my mom purses with macramé, and other gifts too. Also in downtown Juarez there were men making bracelets and pens with woven names on them… and crucifixes. I learned how to make those and I started selling them in school. This is where the new work comes from, the weavings on the dowels.

How did you come to incorporate this approach into your practice?

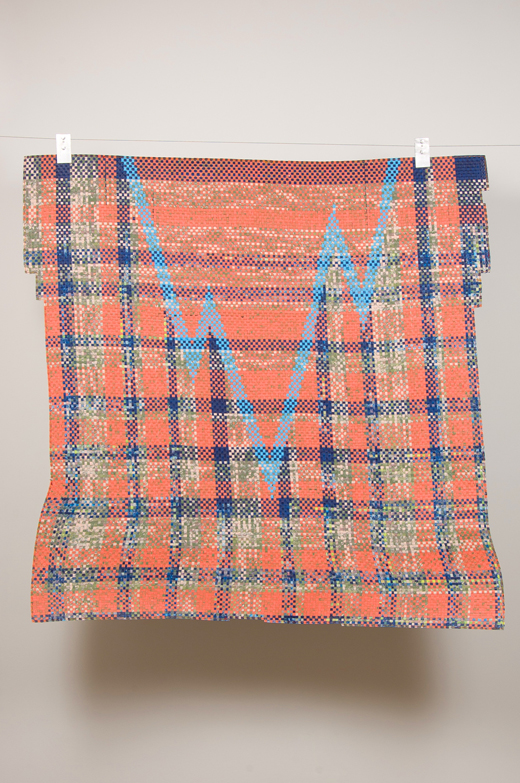

Near the end of grad school I started thinking that Modernism missed an opportunity. Through its self-referentiality it explored a lot of ideas but nixed using the broader cultural associations that come with certain materials. I thought, “There’s a conceptual opportunity here.” This led me to the paper weavings, which were interested in the modernist grid and the painterly gesture. By cutting up the gesture and putting it into the grid I was able to make associations with fine art, but also non-fine art—like basket weavings, textiles, and craft traditions. The weavings also occupy a liminal space; they are weavings, but also paintings, and they are also sculptural, so within the taxonomies of the art world that is a critical position to take.

You use a lot of Christian content in your work, the crosses and religious heraldry. Do you see your work as Christian?

I want my work to be particularly Christian and not be lost in some new age spirituality. In the U.S. fine art context Christianity is often associated with right-wing politicians and social conservatism. With these Christians the only thing we agree on is that Jesus Christ is the Son of God and our Lord and Savior, but beyond that, with regard to politics and society, we have very little in common. In the last two years I decided to make Christian content more prevalent in my work, but I hope my work is rich in content and not just about one message. I’m not interested in making Caravaggio paintings that tell a story. I’m more interested in the materials that the Saints surrounded themselves with. That’s been difficult to do because it’s a negotiation with materiality, content and Christian associations. How that’s resolved, I don’t really know, which keeps me interested.