Lately, I’ve been thinking about the weird inversions of mainstream and underground culture, particularly as regards formats—the vinyl record for example. Talking with Rick and Joe Potts and Dennis Duck (all founding members of the Los Angeles Free Music Society) on my KCHUNG radio zine, they all emphasized what a revolutionary concept it was in 1975 for a bunch of experimental weirdos—the Potts’ band Le Forte Four in this case—to issue their own LP without the imprimatur of a record company.

Of course “Bikini Tennis Shoes”—a collage of Musique Concrète, experimental electronic noise, processed studio chatter and appropriated Papal addresses, packaged in cast-off misprint sheets of Blue Boy and Pinky postcards from the Huntington—didn’t exactly burn up the charts. In fact they couldn’t successfully give away all 200 copies. “People would bring them back,” remembers Rick, “saying ‘Maybe you know someone else who would… appreciate this better.’” Now, copies sell for, well, there’s only one listed on discogs, and they’re asking $743.06.

That’s part of the weirdness—the fetishization of artifacts for their inferred position in a history of cultural resistance or innovation, rather than for their actual content, like they’re props in some nostalgic sitcom—or fashion accessories. And don’t think I’m not talking about The Art World. But the rules of the vinyl game keep shifting. Only a few years after “Bikini Tennis Shoes” every trust-fund punk was starting a micro-label, and there was a still-uncataloged tsunami of DIY releases. Then, with the advent of CDs (and subsequently mp3s), self-released vinyl became first obsolete, then a perversion, then collectible, then a niche consumer demographic—where it got stuck for a good decade.

But the situation has mutated again recently—maybe a critical mass of hipsters has effected a figure/ground shift. The turning point may have been the success of Mississippi Records, which gained international prominence by issuing short-run editions of what are essentially pirated Roots, World and Other music recordings. The record label had become a purely curatorial entity, and moved into the realm of what I suspect to be the future of art-making—the filtration and organization of the overwhelming and exponentially increasing flow of information precipitated by the digital revolution. In other words, collage.

In a medium where you can’t even keep track of the thousands of aggregator sites, stepping down to an obsolete technological format is an elegant way to eliminate 99% of the choice work. Sort of like writing a sonnet, or haiku. One artist who has been expressing himself via a tiny record label for several years is LeRoy Stevens. The LA-based, Chicago native’s most recent release was an example of the kind of historical archival project we need to see a lot more of—a double LP of soundtracks by legendary Angeleno performance artist Barbara T. Smith.

Ranging from abstract loopy electronic drones to a deadpan recounting of a rape, Performance Audio 1969–1988 is the kind of record that—had it been issued at the time of the recordings—would now be selling for $743.06. More perhaps, considering half the contents contain significant contributions from cult icon Joseph Byrd—Fluxus operative and leader of The United States of America. Released on CD or uploaded to ubu.com, this work would sink in the bitstream quagmire. But here it is, getting written up in a fancy art magazine!

Stevens’ vinyl odyssey began in 2009, when he went to every record store in Manhattan and asked the employees to recommend their favorite scream from recorded music, which he then compiled into a single extended caterwaul as Favorite Recorded Scream; an indexical accounting of ecstatic vocal outbursts that got written up in The New York Times. Next up was a détournéed version of the kind of hippie sound effects recordings that flourished in the ’70s—“Across Lake Huron in a Canoe (now with Goose Courtship Displays)” sort of thing.

But the beginning of Dan Peterman’s Waterways—traversing the International Port of Chicago, the little Calumet River, and the I&M canal—is chock-full of industrial noises, including a cranky bureaucrat on a loudspeaker informing the artist that he is “endangering yourself and others.” Side two tempers the irony with a more traditionally bucolic soundscape—escaping upstream from civilization, enacting a miniature Heart of Darkness.

My favorite release on Small World, Mfg. is LeRoy’s own sculptural soundtrack, taken from an interactive minimalist architectural configuration erected in Joshua Tree as part of High Desert Test Sites 2011. Four freestanding sheds connected by hollow square steel tubes are each equipped with wind-driven ventilation turbines modified so that each has a different number of blades. As the wind spins the metal turbines, they beat against an armature to create overlapping rhythmic and tonal patterns that also vary from room to room. The results are hypnotic, and strangely unplaceable for the soundtrack to a site-specific installation.

Stevens’ Barbara T. Smith record was connected with an exhibit at The Box gallery, where he also works, and who will be launching their own micro-label with a 13 vinyl disc box set deriving from their Los Angeles Free Music Society two years ago (and which will include an improvisation with my band F)—small world indeed. Which is exactly my point. Shrinking the world is the medium of the future.

Barbara T. Smith, Performance Audio 1969–1988, 2LP, Small World 2013;

Produced by LeRoy Stevens and Barbara T. Smith

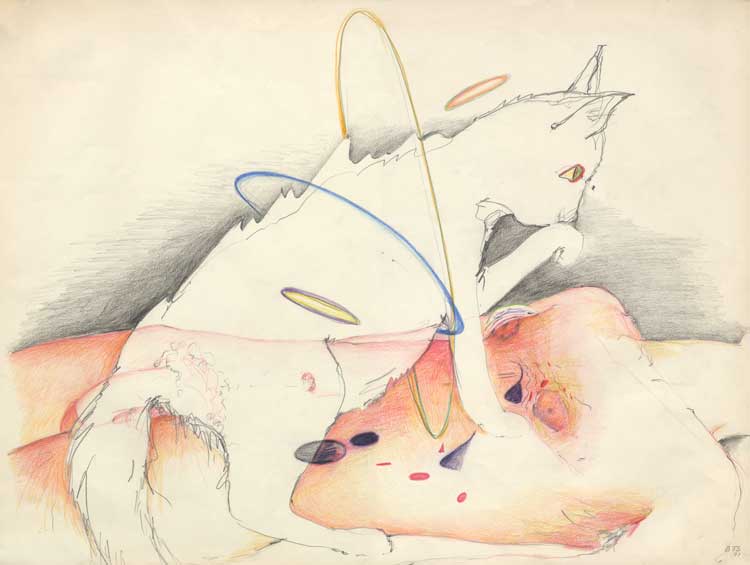

Barbara T. Smith, Untitled Drawing from Sound Piece for Notes and Scores for Sound, 1971. Pencil on paper, 18 x 24 inches