A refreshing fragrance of hyacinth and tiger lilies sets the tone for Thai artist Pinaree Sanpitak’s delicate installation of white garlands, or Ma-Lai, for which her third solo exhibition in New York is named. Continuing with her interest in the body that she has probed through prior large-scale works, the current show, which includes paintings and sculpture, explores the idea of human interconnectedness and bonding.

Strategically hung on two adjacent walls across the entrance of the gallery, handmade diamond shaped flowers made from toile are strung together to represent the tradition of garland making from ancient Thai dynasties. Used widely in religious ceremonies, weddings, celebratory events, and funerals, the garland is an important symbol of unification, and the gesture of being garlanded becomes an honorific signal between the recipient and the giver. Through this indigenous cultural object, Santipak introduces the idea of unity between individuals and further delves into her belief that “the body denotes both the mental and physical, the body and soul.”

Drawn from the her training in Japan, each painstakingly constructed flower, made with the help of an assistant and the artist’s mother, uses the mathematical accuracy and methodology of the origami technique to create geometric forms from fabric instead of paper. Hundreds of white toile stars resembling real posies are securely intertwined to make garlands of different lengths and compositions. Hung together, this installation of symmetrical, aesthetic white flowers emits a sense of serenity not unlike the sensation of security derived from her hammock and flying cubes series. While Sanpitak’s previous works have provided some sort of sensorial experience, here the ambient fragrance of fresh flowers subtly replaces the scent of natural flowers used for making ma-lais in Thailand.

Displayed on the floor at the end of the L-shaped gallery, pairs of cast aluminum breast sculptures referred to as Ma-Lai Connected, 2015, are joined with long stems of lavender, strings of marigold, and strands of carnations bought at the local flower market. In keeping with the symbolic significance of the garlands, the linked balloon shaped objects serving as female breasts, which has long been the focus of Sanpitak’s work, continues her concern with individuals’ physical and spiritual associations. Although the combination of natural flowers with the sculptures appears somewhat gratuitous, the shimmering metal shapes stand out for their conceptual beauty.

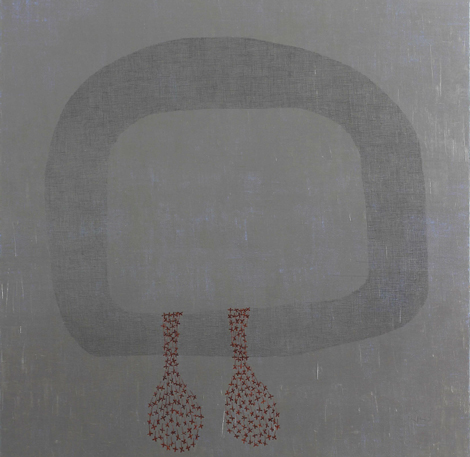

Sanpitak’s most subtle expression of interpersonal unity can be seen through a series of lava gray canvases. Large graphite rectangular shapes with rounded edges are drawn at the center of each painting with wide borders of fine grid like patterns. Reminiscent of the precision of Minimalists like Agnes Martin and Jennifer Bartlett, the lacquered wreaths like borders faintly shimmer through the richly layered slate backgrounds. However, the meditative effect of graphic pattern on soothing grey canvas is disrupted by fragile rust colored breast like formations made with dried flowers that seem tacked on to each rectangular border.

At the end, if one is left wondering about the decorative elements that seem to diminish the impact of the sculptures and paintings—none of it is as important as Sanpitak’s idea to use the garland that is commonplace in Hindu and Buddhist mores to disseminate the significance of non-western conventions.

Tyler Rollins Fine Art

529 W 20th St, 10W

New York, NY 10011

September 10 – October 24