Having redirected his energies over the course of 20 years, from cast-resin sculpture to wall-based works combining painting with steel cables and short lengths of pipe, Peter Soriano has lately dispensed with objects, working on the wall in spray paint and acrylic unencumbered by sculptural concerns. In five elegant, playful paintings, the artist variously recombines graphical elements such as circles, arrows, Xs, brackets and miscellaneous irregular polygons in sprawling, diagram-like configurations that might at first glance be taken to represent cognitive operations—explication, transformation, synthesis—but ultimately refer to themselves and to the wall as a provisional picture plane.

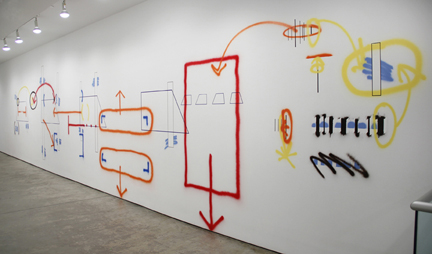

Playing loosely sprayed markings against others that are meticulously hard-edged, these works are executed according to a set of instructions, in the tradition of Sol LeWitt. They are subject to minor variations even though Soriano himself often installs them, the spray can being an imprecise tool. Down the left side and across the bottom of the 13-foot-long CDG #1 (all works 2012) runs a long, sprayed arrow in stop-sign red, which terminates at the base of a segmented column of crisply outlined boxes (Judd stack? Ladder? Filmstrip?) which intersects a downward-sloping series of rectangles made by masking and spraying with bristling dark-brown hatching. The spraying magnifies the vagaries of the installer’s touch, and the way those components overlap provides clues to the sequence of mark-making.

In the case of the nine-foot-high, 38-foot-long Bagaduce #3, installed in the gallery’s narrow front space, Soriano’s working method presents a problem of tense. As a sequence of predetermined operations, his paintings (even when not physically manifest) exist in the perpetual present and are replicated for exhibition, but the experience of a large work is subject to the specifics of its installation and here, an overview of the work is possible only from an acute angle. This awkward placement compels a particular kind of scrutiny. At necessarily close range, the viewer absorbs the work episodically, as one might read a scroll painting. The whole visual field is engaged by a system of symbols and signals in ambiguous relation to its entirety.

This immersion in a wall work’s vocabulary and inner logic is of a different kind than that which we experience in front of a very large canvas. In that case, we understand that the composition extends as far, at least in the literal sense, as the painting’s edges. When the wall is commandeered as the working surface and the picture plane, its physical nature and architectural function are inescapable even as its whiteness dematerializes to become infinitely deep pictorial space. In a sense, a wall work extends as far as the wall that is its support, and transforms that support into something visually elastic, dynamic, contingent. Soriano’s work underscores this paradox of visibility: portable but not “site-specific,” the work’s free-floating figure/ground construction depends on the white of the wall as its site and foundation even while, for a time anyway, rendering it invisible.