A friend of mine spent election night serving drinks at a bar in Highland Park. During the day she worked in her studio—she was preparing for an upcoming gallery exhibition. In the evenings she makes a living bartending. Before the election results poured in, she served manhattans and cranberry-vodkas, and beer later to the drunk and dispirited when Florida was called for Trump. She wondered what good she was doing. Working behind a bar was a means towards making her art, but as she told me later, she began to question her assumptions about her art practice, which only fed into her long-running skepticism of the art world in general. Has art done enough—anything even—to prevent the rise of Trump?

My friend is surely not the only person in the art world questioning whether their profession is furthering the production of a fair and decent society. Skepticism is good, but a closer look is warranted. High-priced galleries, auction houses and mega art fairs are not typically associated with civic investment. But many civic philanthropists also contribute heavily towards the arts. Say what you will about the Koch brothers, but they’ve gifted over a billion dollars to a slew of liberal causes célèbres: public television, higher education, environmental stewardship, criminal justice reform, and the arts.

There is also art, beyond the various Basels and blue-chip art worlds, that takes community partnerships as their medium.

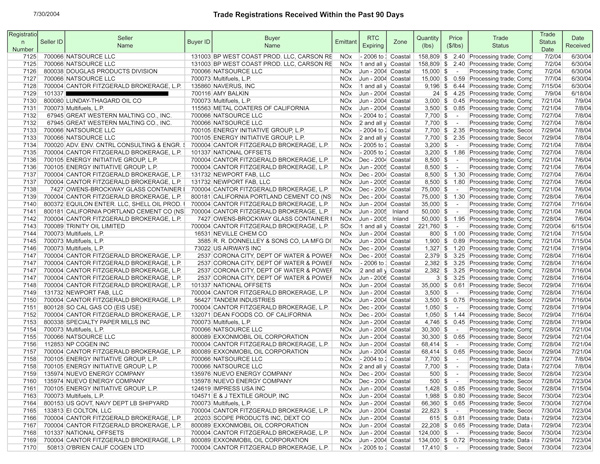

Image from Amy Balkin’s Public Smog project.

Take for example, Amy Balkin’s manipulation of preexisting financial, legal and political activities to create Public Smog. By purchasing and retiring emission offsets in regulated emissions markets, she literally makes parts of the atmosphere inaccessible to polluting industries, thereby creating, for all legal intents and purposes, a park in the atmosphere. Theaster Gates’ Rebuild Foundation takes the race-inflected concept of “blight” and uses it as a medium to rebuild neighborhoods suffering from under-investment, while Tania Bruguera’s Immigrant Movement International—a community space launched with the Queens Museum and Creative Time—provides various educational, health and legal services to immigrants.

Of course, none of these projects prevented this freak-show of a presidential candidate from taking office. Indeed, art didn’t prevent the 2003 Iraq War, either. But to position art in this way creates not only a false choice but a sweeping generalization that ignores the role of the arts in the production—and at times destruction of—culture through metaphor, imagery and symbols.

Image from Amy Balkin’s Public Smog project.

As Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote last month in The Atlantic: “There is nothing ‘mere’ about symbols… Burning crosses do not literally raise the black poverty rate, and the Confederate flag does not directly expand the wealth gap.” Yet it’s hard to overstate the potential of visual culture to move people to extreme ends (Leni Riefenstahl anyone?). How much longer would the Vietnam War have lasted if Americans never saw the grainy black-and-white images of a soldier falling out of a helicopter, summary executions in the streets, or the image of a 9-year-old Kim Phuc badly burned from napalm running down a road, naked and screaming?

It wouldn’t hurt for more people in the various art worlds to ask whether their work is doing the right kind of work. Does your art traffic in the kind of neoliberal moneymaking worldviews that got us into this mess in the first place? Does your work ignore the constant background hum of racial resentment and xenophobic hate in this country?

Creating, writing, researching or participating in art does not excuse one from other civic duties. And even if an artist’s work addresses the above questions, as the work by my friend who was bartending on election night does, there is always room to do more. My friend decided to join in a five-month practicum on the intersections of art and the law in New York City—an extreme and admirable commitment to the election not everyone is able to make. In other words, I don’t think the issue at hand is whether art can do good; a better question might be whether you and your work—within art or outside of it—contribute toward a fairer and more decent society.