Nan Goldin, to borrow a phrase from her friend and fellow-artist David Wojnarowicz, has always lived and worked “close to the knives.” Her most recent published collection, Diving for Pearls, can only intensify our appreciation for her images of that pain and that exultation.

In many ways, Diving for Pearls continues the so-called snapshot aesthetic indelibly associated with Goldin’s name after the 1986 publication of her long-evolving slideshow The Ballad of Sexual Dependency. These quasi-offhand snaps were raw, intimate images of the life of Goldin and her “tribe,” based originally on the Post-Punk, No Wave, gay and hard drug subculture of New York’s Lower East Side: a world compounded of blood and tears; of frothy cum and dirty, sudsy bathwater; of the killing ecstasy of sex and heroin; of cigarette smoke and subterranean sound. It was also a world which Goldin presented as sexually and artistically aggressive, and yet vulnerable in a deeply, even desperately personal way. The world of Diving for Pearls is similar, but transformed as well: less immediately deadly, but more reflective and commemorative.

Self-portrait on New Year’s Eve, Malibu, California, 2006.

Since Goldin tends to shoot her subjects again and again, sequences of images drawn together in the book—for example, her studies of “Kathleen” (1990–96)—produce a non-narrative composite “portrait” that examines its subject in every aspect of her being, from the most formal to the most intimate. But the subject is always “alone” —that is, accompanied only by Goldin and her camera, which functions as a kind of mechanical memory machine, holding in perpetuity both the inelegant poses and passing momentary actions that constitute a life lived at its least self-reflective level: compare, for example, the studied formality of “Kathleen at her opening” (Paris, 1993) to the surprised, yet still-controlled vulnerability of “Kathleen in my bathroom” (Köpenickerstrasse, Berlin, 1994). In the first, we see Kathleen standing proud, erect, elegantly dressed and made up, and holding three yellow-bud roses; yet she looks up and off to her right, out of the frame, as though wistfully projecting herself somewhere (anywhere) else: alone in the darkness and silence of her own special moment. In the other, she stands as though caught out unawares, naked and exposed, if partly draped in a towel, her body open, vulnerable. And yet her face, across which a trace of that vulnerability also flickers, conveys a sense of the momentarily hidden power and substantial presence—as we can see in the bust-length study that immediately follows.

Masumi in her bathtub, Hotel Bauer Palladio, Venice, 2015.

Indeed, Goldin’s individual portraits seem always to fall along this brutal knife edge, between hard-won independence and existential integrity on the one hand, and the mise en abyme of devastating isolation and loneliness, of yearning and desire unfulfilled on the other. And this has produced some of her most poignant work: I am drawn again and again to the sequence of four nude studies of Masumi taken in and around Venice in 2013 , which begins and ends with two inward-turning, self-absorbed figures, the first of whom seems somehow troubled, unquiet, while the last portrays a moment of almost ecstatic, transcendent self-effacement, as though Masumi in the bath had become a kind of tribal Saint Teresa.

There are also a number of double portraits, where these same personal dynamics are played out through a wonderful set of mirrored reinforcements and reversals; however, two other aspects of the current collection especially grabbed my attention.

The first is a pair of grotesque photos of relics from the fire that almost destroyed Paris’ iconic Deyrolle taxidermy shop and cabinet of curiosities in February, 2007: the one (a goat) horribly burned, the other (a peacock) apparently undamaged—a not unlikely metaphor for Goldin’s own East Village tribe: so many of the original denizens (like the ghostly Peter Hujar and David Wojnarowicz that we see in a Bronx double-exposure from 1983) dead from drugs or AIDS, and yet miraculously resilient, able still to display its outlandish beauty.

Young Orphan Girl at the Cemetery, ca 1823–24, Eugene Delacroix, Musee du Louvre, Paris, 2010

Amanda smoking in the café, London, 1996

The second is a series of paired images, created thanks to a commission from the Louvre in Paris, which match contemporary “snaps” against (mostly) decontextualized details of paintings from the Louvre collections. Obviously, the pairs are intended to establish some sort of dialogic relationship with one another, sometimes through formal echoes or mirrorings, sometimes through other more subtle, or personal correspondences. These are almost without exception very powerfully resonant juxtapositions, and concerned with something much deeper than mere influence, or even subconsciously storing visual information for later re-use. There is very little, for example, that obviously connects Delacroix’s “Young Orphan Girl” (c.1823-24) that Goldin photographed in 2010 with her equally intense portrait of “Amanda smoking in a café” (London, 1996) , except perhaps a sense of time-and-space destroying presence. Yet despite its formal brilliance and apparent nod to art-historical sensibility, this strikes me as exemplifying a very subversive strategy.

Indeed, through their association with her contemporary portraits, the historical “fragments” attain to a vivacity that seems to belong much more to Goldin’s world than to their own. Her photographs disrupt the complex interpenetration of nature and artistic model that for critics and historians constitutes the classical tradition, and replaces it with . . . what? With an explosive moment on New York’s Lower East Side, when a dedicated group of radically marginalized run-aways, sexual renegades and cultural outlaws came together to form a tribe and seize for themselves the means of cultural production. This explosive moment lives on in the life of Nan Goldin and her circle of friends, and, at least in Goldin’s photographs it burns with such a brightness that it has become a moment of cultural origination with a vivacity and immediacy that they have never before attained.

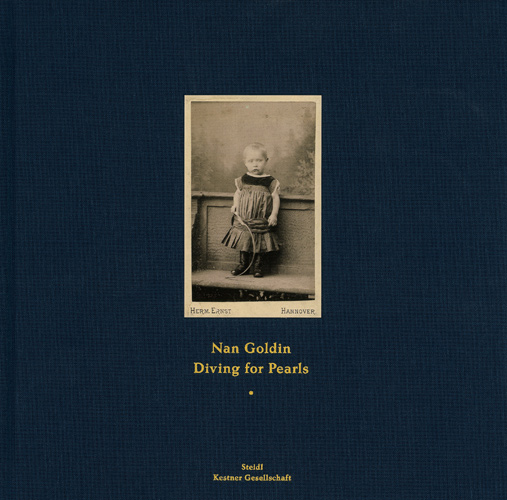

Diving For Pearls, by Nan Goldin

Steidl and Kestner Gesellschaft