The inaugural show at the newly opened Moskowitz Gallery on La Brea Avenue brings together the work of four young and talented artists: Alexa Guargilia, Mitch Weiss, Bill Maass and Adam Moskowitz. Although all four bring distinct technical approaches, distinct visual interests and distinct sensibilities to their work, they all deploy a sharp sense of pictorial structure as well as a subtle historical resonance that encourages, and rewards, a close, yet open-ended viewing experience.

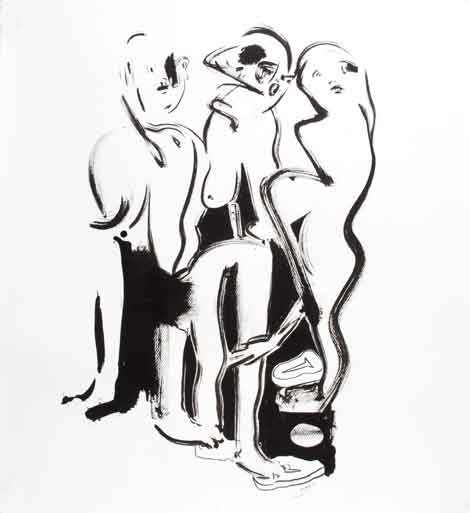

The most overtly historical work is probably Alexa Guariglia’s Three Graces, a smallish ink drawing (22 x 21”) that combines a swift, sure hand with a light almost, comic touch: I especially like the way the two flanking figures seem to react in surprise (their expressions both physiognomic and psychological variations on a theme) to some event taking place as it were “off-camera,” while their beaky and pendulously-breasted companion provides a balancing turn in the opposite direction. The subject, of course, has a venerable history, here refracted through Picasso’s Demoiselles and further defamiliarized by the inclusion of two mysterious T-bone steaks. Despite the look almost of a sketchbook exercise or self-referential visual note, this is clearly a work where the superficial appearance masks a thoughtful and delightfully iconoclastic conception.

Lisa (ink and gouache on paper, 5’ x 7’), a loosely organized but tightly controlled abstraction, likewise gives the appearance of rapid execution. In reality, however, that initial rapidity of attack has been subjected to a meticulous, almost miniaturist reworking. Although difficult to appreciate in reproduction, the work itself encourages a complicated viewing regime, where a constantly changing approach and withdrawal establishes a dialectic between overall design and minute, relentlessly crafted detail that held my attention effortlessly and provided a wonderfully rich experience.

There is, on the other hand, nothing about Mitch Weiss’ photography that suggests rapidity of execution, although, like all good street photographers he clearly has an eye for the significant moment unfolding in real time, as well as the ability to capture it as if without effort. (He also produces excellent studio work, for example the 17 x 17” Archival inkjet Fedora: a splendidly tactile study in dark form scintillantly burnished by light against a dark ground.) His NYC: Skylines (16 x 24”, Archival Inkjet Print) might be read as a slyly Mannerist “portrait” of the iconic Chrysler Building, seen off-center and in deep space, like a landscape motif in a sixteenth- or seventeenth-century Dutch print. At the same time, the photo provides a brilliant study in overlapping planes defined as a series of vertical bands and narrow rectangular fields, some transparent, some opaque, that tend to collapse without quite flattening the space of the view: a modernist vision at once concrete and abstract, rigorous in its geometry and extraordinary in its attention to detail. Again, it’s a work that more than repays a carefully systematic viewing.

It is perhaps too easy at first glance to perceive echoes of Francis Bacon in Bill Maass’ mixed media portraits. Too easy because, despite the obvious formal debt or (perhaps better) historical nod in Bacon’s direction, Maass seems to be about something quite different. Whereas Bacon’s figures (whether portraits of not) are clearly riven by excruciating pain, unrelenting terror, the sheer blackness of Bacon’s own personal abyss, Maass’ sitters, for example those portrayed in his paired Two Untitled Portraits (each 25 x 27”, Mixed Media), seem comfortably situated within a rather different historical niche, that of the ¾ view, bust-length Renaissance portrait. Maass manipulates that format skillfully, but, one might say, without overt malice. Such Renaissance pairs, for example, usually match a man and a woman (most commonly husband and wife); Maass, on the other hand, pairs two men. A comment on contemporary sexual politics? Perhaps; but also an interesting puzzle in the nature of portraiture. What separates the two portraits in this case, is not gender, but the relative extent to which the features of the sitters appear deformed. It is as though we are being asked to consider the nature of the portrait as such. Is a portrait the embodiment of an idealized vision or the externalization of an exercise in individual self-fashioning? Is it the record of an actual appearance, a real physiognomy, or the excavation of a malign and normally hidden interior being? In any case, the restricted palette tells us that (Giorgio Vasari’s assertion of the presenting power of portraiture notwithstanding) Maass means to stress the fact that the portrait is the residue of an act of representation, beholden not just to the sitter but also expressive of the “painter’s share” in its production – a reassertion of artistic presence.

As if to underline that fact, we can turn from the individual portraits to a quasi-abstract work like Elephant III (25 x 26”, Mixed Media). Here we seem to be confronted with a kind of archive of physiognomic fragments, deconstructed portraits, bits and pieces that can be assembled “off the shelf” into legible if “counterfeit” individuals: indeed, a proverbial “elephant,” awaiting only the arrival of the artist, or the committee, to assemble it from its scattered constituents.

Finally, we can turn to the work of the gallery’s curator, the photographer Adam Moskowitz. Although the most abstract of the work in immediate appearance, Moskowitz’s exhibited photos, for example Counter-Form Inorganic Seattle I (12 x 18”; Archival Inkjet Print), are all digital double-exposures of concrete architectural forms. And although they might hark back within the photographic tradition to the Soviet avant-garde, even some of the work of Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, Moskowitz’s real touchstone is not so much within the visual arts, as within music: he is both a photographer and a violinist who studied at the Berklee School. Indeed, the series designation Counter-Form is intended to evoke the notion of counterpoint, and the way in which the formal juxtapositions develop, as a set of complexly overlapping and just off-register regularities seems as redolent of Bach as it does of, say, Archipenko.

In sum, Adam Moskowitz and his director Brooke Gerson, have given us a more than creditable inaugural exhibition. The work on view highlights a quartet of bright, talented young artists, of whose work I look forward to seeing more in the future.

exhibition ends December 1, 2013

743 N. La Brea

Los Angeles, CA 90038

www.moskowitzgallery.com