There was a moment between the late 1960s and early 1970s when mainstream American mass culture seemed to heave a collective sigh of relief. With the first major convulsions of the American civil rights movement and the trauma of recent political assassinations behind them, a nation of middle-class suburban consumers yearned to go back to their backyard barbecues and bridge tables and just let the kids get on with raising their consciousness, protesting the Vietnam War, and doing other things in schools and bedrooms they were content to ignore—as long as the kids secured admission to their preferred colleges and universities.

It was as if the Age of Anxiety had given way to an ‘I’m okay, you’re okay’ transactionally analyzed age of consumer placation. There would be nightmares, headaches and hangovers to come. (The U.S. would not be entirely out of Vietnam for several years. You can tick off some of the others: the Nixon election, Altamont, (for some of our parents, even Woodstock), the Manson murders (at least in Los Angeles), the Pentagon Papers, Watergate, etc.) But there was football to consider; and that Paraphernalia skirt and Abercrombie & Fitch raincoat to try on. The problem was not that the Revolution would not be televised; the problem was that the Revolution could not be televised, which was a non-starter for a country in which there were far too many commercial products waiting to be promoted and sold. America had no problem with hippies as long as they steered clear of mainlined speed, attended to personal hygiene and above all, continued shopping. ‘Flower power? Sure, how much are you asking?’

It was as if the Age of Anxiety had given way to an ‘I’m okay, you’re okay’ transactionally analyzed age of consumer placation. There would be nightmares, headaches and hangovers to come. (The U.S. would not be entirely out of Vietnam for several years. You can tick off some of the others: the Nixon election, Altamont, (for some of our parents, even Woodstock), the Manson murders (at least in Los Angeles), the Pentagon Papers, Watergate, etc.) But there was football to consider; and that Paraphernalia skirt and Abercrombie & Fitch raincoat to try on. The problem was not that the Revolution would not be televised; the problem was that the Revolution could not be televised, which was a non-starter for a country in which there were far too many commercial products waiting to be promoted and sold. America had no problem with hippies as long as they steered clear of mainlined speed, attended to personal hygiene and above all, continued shopping. ‘Flower power? Sure, how much are you asking?’

This kind of commercialized ‘flower power’ was secreted directly into the culture by way of heavily hormonalized middle and high school students, Madison Avenue, and of course television. There was a profusion of flowers and hearts and stars and bubbles around every mash note, doodle, school dance or assembly announcement. You saw it on television in the Laugh-In joke wall, with soon-to-be-stars like Goldie Hawn bursting out from their perches with some impossibly cute-funny line that would elicit a sardonic-funny comment from hosts Dan Rowan or Dick Martin. (I’m sure you’re too young to remember the original TV ‘it girl’ Judy Carne, who became famous for going into on-camera ‘sock-it-to-me’ convulsions.)

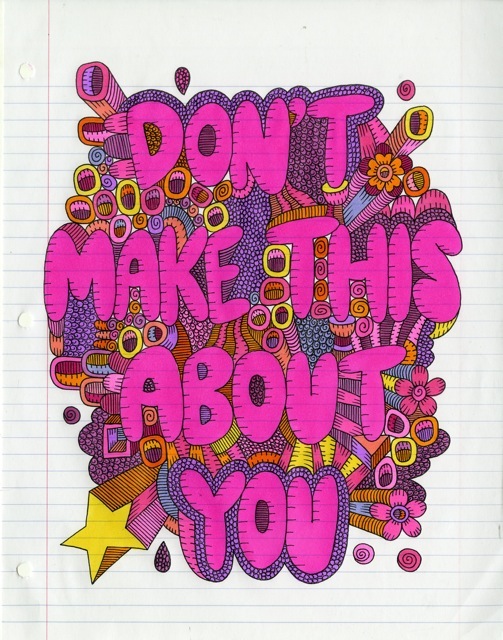

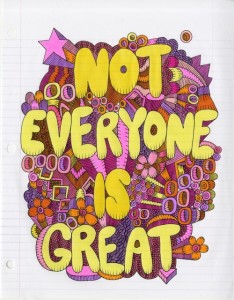

The effect rippled outward into almost every domain of communication and entertainment. The greeting card industry was all but made over by it. There was a period of at least five years when it was almost impossible to purchase a greeting card without the kind of cartoony bubble-gum lettering and variably dense, almost rococo doodling surrounding or interwoven into the message. The style was usually some variation on tongue-in-cheek sarcasm, over-the-top exaggeration, or dead-pan banality, with the punch-line or ‘sincere’ sentiment saved for the inside of the folded card. (It was actually not unlike the kind of joke-wall humor that prevailed on NBC’s Laugh-In, with varying degrees of sophistication or sentimentality.) The formula could be reversed depending upon the desired effect.

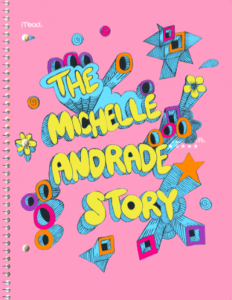

Michelle Andrade did not grow up (as far as I am aware) in this world; but she knows it the way JoAnne Worley knew her way around a feather boa. (I allow for the fact that she grew up in suburban Los Angeles, which has always been the epicenter of this kind of consumer culture.) In other words, she understands the dysfunction, distrust, and discontent those words, letters, images, symbols (almost a precursor to contemporary digital-culture emoticons and ‘emojis’) wrap around, camouflage, evade and conceal. Not far beneath the coy sentiment and ersatz optimism was an emotional universe of confused dismay, emotional insecurity and uncertainty, intimidation and anger. The ‘back to business-as-usual’ mentality of this period had an undercurrent that more or less responded, “Bullshit.”

Michelle Andrade did not grow up (as far as I am aware) in this world; but she knows it the way JoAnne Worley knew her way around a feather boa. (I allow for the fact that she grew up in suburban Los Angeles, which has always been the epicenter of this kind of consumer culture.) In other words, she understands the dysfunction, distrust, and discontent those words, letters, images, symbols (almost a precursor to contemporary digital-culture emoticons and ‘emojis’) wrap around, camouflage, evade and conceal. Not far beneath the coy sentiment and ersatz optimism was an emotional universe of confused dismay, emotional insecurity and uncertainty, intimidation and anger. The ‘back to business-as-usual’ mentality of this period had an undercurrent that more or less responded, “Bullshit.”

Some of the anger stemmed directly from the fact that it was hard to get serious guidance, whether ethical or simply practical, from authority figures (parents, community leaders, teachers, counselors) who took this jive mind-set so seriously. Andrade essentially puts herself in the position of the schoolgirl facing her blank page of notebook filler paper, who, instead of regurgitating the standard sentiments, channels the teacher’s (or other) culturally tone-deaf rote recitation, and the underlying emotional dissonance and disconnect.

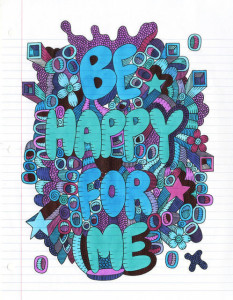

I think the underlying message of so many of those cards (signage, doodles, even commercial advertising) was a desperate plea for reassurance in the absence of a coherent perspective on the morphing contemporary cultural-political condition: ‘I don’t know what I’m doing, but please just be happy for me right now.’ (Andrade, needless to say, picked up on this right away.) The cross-generational read was that we were all in on the same joke: ‘Beyond all these dead flowers, I know that you see we’re really in perfect agreement.’ (For many of us, of course—settling into lock-step careers in professions and management—this would prove to be true. I give my own parents some credit for not buying into this sentiment, recognizing that I was becoming one of the people they were warning us against—probably from about age six.)

I think the underlying message of so many of those cards (signage, doodles, even commercial advertising) was a desperate plea for reassurance in the absence of a coherent perspective on the morphing contemporary cultural-political condition: ‘I don’t know what I’m doing, but please just be happy for me right now.’ (Andrade, needless to say, picked up on this right away.) The cross-generational read was that we were all in on the same joke: ‘Beyond all these dead flowers, I know that you see we’re really in perfect agreement.’ (For many of us, of course—settling into lock-step careers in professions and management—this would prove to be true. I give my own parents some credit for not buying into this sentiment, recognizing that I was becoming one of the people they were warning us against—probably from about age six.)

The truth was we weren’t so happy. We were anxious, uncertain, and … kind of blue. We had put a ‘tiger in every tank’ and a man on the moon, but, as Miles Davis might have put it, ‘So what?’

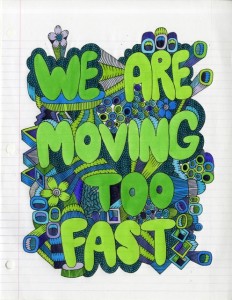

If the latter half of the 1970s was the hangover from all that, the 1980s was a sharp right turn into the power of denial—or simply power enabling denial. If the reconstituted flower-power cult of coy and cute had disappeared [though of course it hadn’t entirely—see my next post], it was simply because we were all moving much too fast to bother doodling in all the curlicues. The new cult was multi-tasking—just more American managerial bullshit. There’s probably a book in this; but Sinclair Lewis isn’t alive to write it.

If the latter half of the 1970s was the hangover from all that, the 1980s was a sharp right turn into the power of denial—or simply power enabling denial. If the reconstituted flower-power cult of coy and cute had disappeared [though of course it hadn’t entirely—see my next post], it was simply because we were all moving much too fast to bother doodling in all the curlicues. The new cult was multi-tasking—just more American managerial bullshit. There’s probably a book in this; but Sinclair Lewis isn’t alive to write it.

It hasn’t changed much in the intervening years. Cher could have told you that in 1968. “Men just keep on marching off to war…,” as she and then-partner Sonny Bono sang. It’s just gotten deadlier (yet not deadly enough: we do a better job killing off other species than we do killing our own). The technology improves and refines, and the planetary biosphere continues hurtling towards destruction.

Andrade gets this, too. She’s emptied out some of her recent work, as if in a hurry to get to the point and bridge a few more recent generational aesthetic demarcations. There’s a sharper fragmentation and distancing in this more streamlined, occasionally hard-edged, minimalist style. Some of her multi-color screenprints and acrylic-on-linen paintings look as if she were trying to translate the graphic style of Sister Corita Kent for the skate-and-screen generation, by way of a Korean strip mall. “Validate Me” (2014) might just be the headdress we all wear. (In its neon colors, I can easily see this over the door of a nail salon: ‘Free validation with your mani-pedi.’) “Come On” (2014) tumbles out of its rectangular configuration of irregular polygons and trapezoids. Please—before we blow apart completely and there’s nothing left.

Andrade gets this, too. She’s emptied out some of her recent work, as if in a hurry to get to the point and bridge a few more recent generational aesthetic demarcations. There’s a sharper fragmentation and distancing in this more streamlined, occasionally hard-edged, minimalist style. Some of her multi-color screenprints and acrylic-on-linen paintings look as if she were trying to translate the graphic style of Sister Corita Kent for the skate-and-screen generation, by way of a Korean strip mall. “Validate Me” (2014) might just be the headdress we all wear. (In its neon colors, I can easily see this over the door of a nail salon: ‘Free validation with your mani-pedi.’) “Come On” (2014) tumbles out of its rectangular configuration of irregular polygons and trapezoids. Please—before we blow apart completely and there’s nothing left.

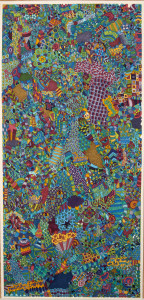

If you look closely at some of her more familiar densely inked notebook paper drawings, though, you’ll see that it’s not all hearts and flowers (or stars and curlicues). Even the gaping soft smiley orifices (not unlike the toothy ‘Ego’ rendition of the trademark Murakami ‘DOB’ figure) might just be lamprey heads; those coiled forms, maggots. Hard-edged geometric extrusions here and there resemble hardware—nuts, bolts, screws; in other words the stuff of IEDs and anti-personnel explosive devices. In a sense, these are all controlled ‘explosions.’ In her more ambitious, expansive ink drawing/paintings, Andrade builds an emotional geography tapestried with imbrications of the sharp and sweet—candy-colored amphetamines, barbiturates, Valium and similar dolls (or just candy)—amid chevroned, lozenged, honeycombed, or harder-edge stuff, in which the verbal signposts are all but lost. “Like Me” (2014) tumbles out of its cascade like a Christ riding into James Ensor’s Brussels. ‘I’m Zoning Out’ flares into blank white space, leaving a Peter Max-worthy ‘SORRY’ bubbling off the top of the hot pink lava in which “You Were Never There” (2014) is left forlornly sinking.

If you look closely at some of her more familiar densely inked notebook paper drawings, though, you’ll see that it’s not all hearts and flowers (or stars and curlicues). Even the gaping soft smiley orifices (not unlike the toothy ‘Ego’ rendition of the trademark Murakami ‘DOB’ figure) might just be lamprey heads; those coiled forms, maggots. Hard-edged geometric extrusions here and there resemble hardware—nuts, bolts, screws; in other words the stuff of IEDs and anti-personnel explosive devices. In a sense, these are all controlled ‘explosions.’ In her more ambitious, expansive ink drawing/paintings, Andrade builds an emotional geography tapestried with imbrications of the sharp and sweet—candy-colored amphetamines, barbiturates, Valium and similar dolls (or just candy)—amid chevroned, lozenged, honeycombed, or harder-edge stuff, in which the verbal signposts are all but lost. “Like Me” (2014) tumbles out of its cascade like a Christ riding into James Ensor’s Brussels. ‘I’m Zoning Out’ flares into blank white space, leaving a Peter Max-worthy ‘SORRY’ bubbling off the top of the hot pink lava in which “You Were Never There” (2014) is left forlornly sinking.

Michelle Andrade is all there—which is both her great gift and (possibly) emotional handicap. The world does not make it easy for those who refuse to buy into the ‘official’ anesthetized version of emotional (or even physical) reality. Kind of Blue is the kind of greeting card I never sent or received, but probably the subtext of half the things I ever felt between six and twenty-six. Fortunately, a few artists were there to confirm my hunch that, although things were decidedly not okay, the beauty might be its own consolation.