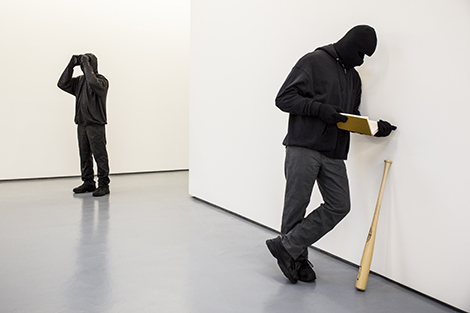

John Baldessari once said that art should make you stop and look as you’re crossing through a museum. Mark Jenkins’ sculpture-installations certainly break one’s forward momentum. On entering the gallery you’re confronted with a clothed leg and shoed foot growing from a flower pot; on the left, a child’s ski mask, tennis shoes, black hoodie and matching sweats reveal a gun. Around the corner, a ski-masked adult has rested his baseball bat against the wall, which he, too, leans on while reading a book. It’s as though the child had outgrown his shell and moved, like a hermit crab, into a larger one, trading his violent weapon for something only a bit less vicious. Jenkins’ best pieces, like Standing Reader and The Bird Watcher (all works 2015), incite narratives.

Jenkins crafts these neo-scarecrows from castings of his own body—or, in the case of the child-sized work, a relative’s—and affixes them in reality or surrealizes them. In House of the Lord, the figure’s head is a birdhouse with a yellow finch staring out. Though the masks and hoodies are empty, standing beside these corporeal still-lifes you feel as though they’re about to turn to you and say, “Yeah? Can I help you?”

Though these pass Baldessari’s test, context matters. And with street art—where Jenkins’ work is usually found—context matters even more. A catalog at the entrance to the gallery shows these, or similar, sculptures in the wild, and it’s impossible not to see how much better they’d work in situ. Imagine if, instead of seeing Reader in a white-walled gallery off La Cienega, you stumbled across him while walking past a graffitied wall on La Cienega.

Castanier would have done better to flip things. The gallery’s upstairs office space showed works to greater effect: a boot kicking through a still life; an ax-holding arm leaving a frame; a child’s torso, legs and shoes leaning against, as though the subject’s head was through a brick wall. Why? Because the ax-wielding arm was not hung, but propped against the wall as though it had threatened the gallery owner to leave it the fuck alone; the boot-kicker was hung with non-Jenkins paintings nearby, creating a sardonic counter-kick; and the boy seems as though he got bored with the computers, paper shredder and art-world business that surrounded him and decided to see what was happening on the other side of the gritty, unpolished brick wall.

Jenkins’ work suffers from the same ailment as all street art exhibitions: once it moves into a gallery, something is lost. With the rise of urban art as art-for-suburban-homes, galleries need to re-think how material is presented. Castanier moves in the right direction with the single piece outside its pristine facades. A hooded figure sits on the gallery’s sign above La Cienega, both figure and sign dripping with the same blue paint, as though showing visitors that he, and the work inside, can rise above gallery constraints.