Marc Horowitz has shifted in the past few years from his early work, bridging performance, social practice, entertainment and social media, into the more traditional practices of painting and sculpture. “Interior, Day (A Door Opens),” his show at Depart Foundation last year, demonstrated publicly for the first time the extent of that shift. Two recent solo shows of his painting and sculpture—the first at Johannes Vogt in New York last May and the second at China Art Objects in Culver City in September—reaffirmed his move in this direction.

Horowitz became an Internet star by pushing humorously—and at times uncomfortably—against social boundaries while the culture at large was still making sense of invasive social media creep. He seems to enjoy playing provocateur, at least a benign one, donning a sly smile that betrays a twinge of sheepishness when he enters territory that may make people guffaw or roll their eyes in exasperation. Many of his performances, like Anonymous Semi-Nudist Colony—Nampa, Idaho (2009), have been aimed at getting people to move beyond being spectators to joining him in the mayhem. He appears perfectly at ease in the role of the gregarious stranger, inviting others to interact with him as a friend, and in doing so, confounding expectations.

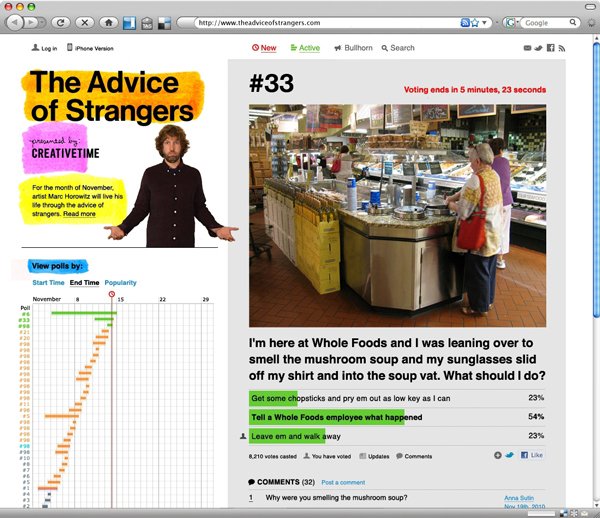

The Advice of Strangers

At times, this has caused him grief. The Advice of Strangers, his 2010 online performance that crowd-sourced his own daily decisions on mostly pedestrian matters, created tension for him both personally and professionally. In one of the therapy sessions that he broadcast on the web and became a regular feature in the month-long project, he discussed, as dictated by Internet voting, his relationship with his mother. He ended up taking down the video after his mother called to express her disappointment.

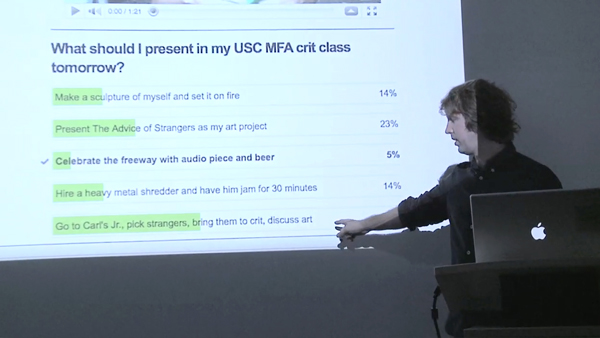

It also set Horowitz up for criticism at USC where he was starting his first semester as an MFA student. He had committed to the project and received funding from the nonprofit New York organization Creative Time before receiving his acceptance to graduate school. He said that he started taking heat for the project during the first group critique, which was led by arts writer Bruce Hainley. “He compared me to Hitler in that first crit,” Horowitz said. “He was like, ‘There was a guy with a funny-looking mustache. He was a fascist, too.’ And I was just floored. The students jumped on the bandwagon, too, and I just got taken down.”

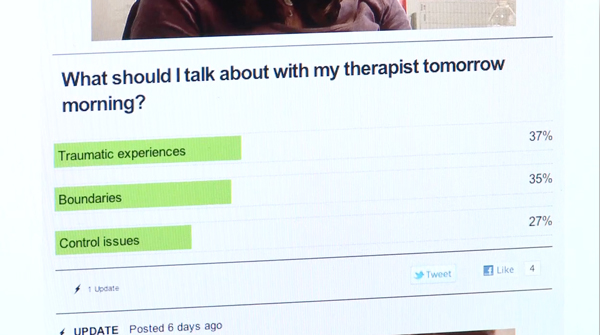

Horowitz with therapist

At issue was that Horowitz limited the possible scenarios by restricting voting to five or six options each day. For example, he would ask the Internet to vote on what he should discuss with his therapist in that day’s session from a list of options: his mother, ex-girlfriends, school, etc.

Horowitz said that when Hainley challenged him to “open it up,” he thought, “Have you ever seen a live show, and you ask, ‘What should I do next,’ and people say, ‘Kill yourself.’” He had already done a three-month performance broadcasting his life live, 24 hours a day (Talkshow 24/7, 2008–09). “It was miserable, but I learned that valuable lesson: you can’t just open yourself up to the group and what they want.”

One can sense the cumulative toll this had begun to take in a seemingly insignificant scenario filmed at Echo Park Lake for The Advice of Strangers. That day’s poll had required him to paddle an inflatable mattress on the lake while wearing underpants over his head and marshmallows glued to his chin. This seemed to cause him genuine distress. As he glued marshmallows to his chin, Horowitz wondered aloud, “What is wrong with me? How did I get myself into this?”

The fallout from the project marked a change in his direction. “I started to go back inside. That’s when I made that dust video (The Title is a Drawing II, 2011). I was so depressed after that. It’s just two dust clouds talking. It’s very like Waiting for Godot, very road-trippy.”

In his videos, Horowitz exudes down-to-earth charm. In person, he is just as friendly, but without the sales and marketing demeanor that comes across in some of his early projects—Anonymous Semi-Nudist Colony—Nampa, Idaho (2009), Errand Feasibility Study (2005), Sliv & Dulet (2002–03). He attributes this to a few things. “When I was a kid, I was moved around a lot, so I had to adapt very quickly if I wanted to have friends and be integrated. I must have moved around 50 times. So it gave me this chameleon-like ability to integrate. And also being from the Midwest—I think people from the Midwest can talk to anyone, anywhere, anytime, about anything.”

Horowitz came to art circuitously. He recalls taking a few art classes as a kid, but he didn’t return to it until his senior year in college, when he enrolled in a class with the noted Indiana University painting professor, Robert Barnes. “My first degree was in marketing and microeconomics. I think that made me a real person.”

The Advice of Strangers

His disregard of societal conventions may also have its origins in his early years. “I left home at 15. I had to scrap it all together myself, and so for me, there are no rules,” he said. “You mix that with this ability to integrate and it’s kind of a dangerous imbalance.”

His response to Hainley and the grad school experience can be summed up in his own words: “I hate authority, and I don’t like being told what to do.”

While taking the painting class with Barnes, he began to think seriously about art. “I fucking loved it and realized I may have made a mistake studying business and not art. I met all of the BFA students because I started hanging out around the art building and studios.” Wanting to be immersed in the scene and to have a space to paint, Horowitz quickly devised a plan to secure his own studio. He went to the art office and said he was an art student who had transferred from Ball State. It took some finessing, but they finally gave him a key to a new studio. “And just like that I was a transfer art student,” he said.

After graduating, Horowitz worked out a way to continue his art spree. “I stole a bunch of money from a parking garage that I worked in, and I took myself through Europe for seven months and went through museums and galleries—everything I could see—and taught myself art history. I came back and went to work in the first dot-com boom in Mountain View doing IPOs. At night I was taking painting classes.”

Freedom This And Freedom That, 2016, fabric, acrylic spray paint, epoxamite, copper, acrylic and clear coat.

After two years, he ended up with a scholarship to attend SFAI just as the dot-com boom was going bust. “I was squatting in a cookie factory, going to SFAI, living the fucking dream.”

At SFAI, Horowitz studied with Harrell Fletcher and John Rubin, two early social practice artists. “I realized I didn’t have to be a studio artist,” he said. “I didn’t have to be a lonely painter. I could be a freak. And I could use me. I was the studio. I could be out there and do performance and video.

Interested in merging business and art, Horowitz proposed a project for New Langton Arts, a nonprofit space in San Francisco (it closed in 2009). His fake company, Sliv & Dulet Enterprises, hired 30 artists to act like business people who were developing a seasonal line of products and services. Horowitz was Burt Dulet, and artist Jon Brumit played his partner Kyle Sliv. Meetings were filled with self-congratulatory talk that mimicked corporate-speak. (Some of the material is still available at www.slivanddulet.com and http://marchorowitzarchive.com).

When San Francisco public TV station KQED produced a special on the seven-week project, Horowitz realized he could rely on third-party news sources to document his projects. “It became this hybridized news story, entertainment documentation, and I didn’t have to do anything. After that I had a pack mule in SF that I did my errands on. So the news, again, picked it up.”

The Thermal Shows This Weird Aura Around The Exoskeleton, 2016, Oil, oil stick, watercolor, liquid vinyl, charcoal on canvas in artist’s frame.

The Today Show and People magazine covered his “National Dinner Tour” (2004), a project that began with his phone number, and an invitation to call him for dinner, appearing in a Crate & Barrel catalog product shot. “It was fascinating. I was playing in this other realm, riding this line between art, entertainment and news. I honestly didn’t know how to define what I was doing,” he said.

The exposure from the dinner tour led to an offer for a TV show, representation at a major talent agency as a digital personality and an overture from a high-profile tech company for a major marketing role. By 2007, his YouTube channel had built a substantial following. “It was this hybrid between tech, entertainment, art, culture. I never knew how to introduce myself. It was very fluid. I could go to a boardroom meeting at NBC, and the next thing, I’m in Hayward doing a talk show. It got to be a little much for me.”

“I feel like I got too far into the mouth of entertainment, and I had to compromise too much. I was getting all of my projects paid for.” Sony had given him a small fortune for “The Signature Series” (2009), when he drove across the country in a series of routes that traced the shape of his signature.

Is This Stick Special? 2016, oil, oil stick, watercolor, liquid vinyl, charcoal on canvas in artist’s frame

In spite of the success, he began to feel disconnected. “I wasn’t happy with the work I was making anymore. It felt like I needed a check. And I also needed to be part of a community in LA because I was really just going to auditions, and I was part of an entertainment community. And I couldn’t stand those people. Most of the people in the entertainment world who I was hanging out with had no aesthetic.”

“That’s why I went to grad school,” Horowitz said. “I was getting lost. And it [his work] just needed a little more tweaking. It needed a little more thought. That’s what I thought at the time.”

Despite the hellishness of grad school, he found some common ground with Charlie White. “He was the one who got me into school,” Horowitz said. “He was the one who really pushed for it. He also rides that commercial line—well, he did—with a lot of his projects.” White was also the person who gave Horowitz the one piece of advice he still hangs on to. “Charlie White said, ‘Kill the clown, but keep the comedian.’ I swear, all I got out of grad school was that little bit of advice. And that really changed the course of everything I was doing.”

When he finished at USC, Horowitz found that galleries in LA were reluctant to take him on. His work was ephemeral, and there was no object. But he doesn’t consider his shift to painting and sculpture as being driven by the difficulty of monetizing the Internet and media-based work he was doing before.

The Advice of Strangers

“I think it’s a furthering of the trajectory inward,” he said. The last public piece that he did was The Advice of Strangers. Among the short videos that followed was Moving (2013), a surreal, life-in-hell kind of two-character drama, in which two pink creatures confined to a small room hack apart a large block made of hydrocal and foam. After making that video, Horowitz realized that he wanted to make sculpture. “What I was left with after that project was a big block, and I thought, ‘That is just magnificent.’”

In spite of the pleasure he expresses in response to painting and sculpting, Horowitz concedes that it doesn’t meet the need for social interaction that his early work satisfied. But he feels that the terrain for performance has changed, and he has lost interest in performing in public. “Bringing it back to the dust video and the pink guys chopping, I want the paintings and the sculptures to operate in that head-space, this other world, this other public.”

Installation view, “Dawn of the zone,” at China Art Objects Galleries.

Horowitz’s painting and sculpture exhibit the same kind of quirky mirth that runs through his video and performance. Deconstructing master paintings and setting them to titles taken from the dialog of a popular movie (Transformers, 2007), as he has done with recent works (for example, This is easily a hundred times cooler than Armageddon. I swear to God!, 2016) gives them an absurd theatricality. And possibly a way to think of integrating old and new: “I think I really want to start making videos again. I have this shelving system set up where there’s a painting in the front, a couple of shelves in the back, and then there’s a video screen behind the painting. So when you go around the painting, there’s a video. It’s a really interesting display. I’ve been trying to explore it for four years and never been able to do it right. But something in that is having sound and color and light on the back of a painting, surrounded by ephemera and sculpture. I like everything coming out of video, but I’m trying to figure out how to tie those worlds together.”