Propped against the wall of her second-story Hollywood Boulevard studio, three of Liat Yossifor’s gray paintings—each about seven feet by five feet—in various stages of completion sit perched on low wood supports. Yossifor’s high-ceilinged studio feels spacious, if rather austere; other than her paintings, supplies, a table with tools, and an old paint-stained leather sofa, there is little else.

Yossifor’s 2010 show at Galerie Anita Beckers in Frankfurt, Germany, featuring figurative work made during her residency at Frankfurter Kunstverein and in large part as an exploration of her deeply felt connection to German Expressionist painting, was her last body of identifiably figurative work. On her return to Los Angeles, Yossifor expected to resume where she left off in Germany, but in 2011, with three months to go until her solo show at Angles, she scraped the paint off every canvas and started over.

It was during this period of compressed production that Yossifor intuitively arrived at the process she now uses, painting in three-day sessions while the paint is still “open.”

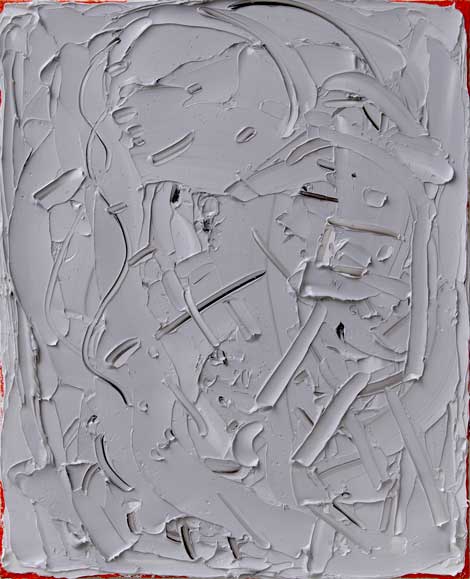

Yossifor’s gray paintings are most easily identifiable in connection with AbEx and the New York School. She advances the idea that as she makes large gestural sweeps with a palette knife, or even small, incisive gashes in the surface of the paint, she imbues the painting with some kind of emotive meaning. She shies away from associations with Lucio Fontana, who slashed his canvases, but there is more than a hint of trauma in her works. They encrust both a battle with the medium and within herself.

A more recent affinity is the similarity to Gerhardt Richter’s squeegee paintings, in which he obliterates his initial lively color fields using custom tools. Robert Storr considers Richter as having decoupled the hand from the gesture. Unlike Richter’s systematic and rectilinear movements, Yossifor’s motions are anchored in her body, even through her use of palette knives. As she works the surface of her paintings, she obliterates multiple layers of possible visual outcomes. She rejects stopping short of working the canvas for three days, even if it means, as it often does, entombing successful abstract pictorial solutions or compositions in favor of a cycle of writing and rewriting a painting’s surface. Yossifor often refers to her painting in terms of a personal struggle combined with an aesthetic one.

While Yossifor’s current work is abstract, there remains a figurative element. “I know that I can’t ever completely empty the shape. That’s about pure abstraction.” Instead, she says she is putting her shape in the painting. This is borne out in the thickness of her surfaces, the multiple folds of paint tucking under or lapping over, like flesh. She likens her work to Gutai artists grappling with mud or to the photos of Ana Mendieta covered with plant matter and the works where she left impressions of her body in the ground.

Often Yossifor develops three or four paintings at once, oscillating her movements between them. “There are bodies in there, in a sense,” she says; multiple viable works exist in each canvas as reflections of her body, even her psyche, within a reverse archaeology of pigment. Sometimes present in the discussion of Yossifor’s work, and perhaps a way to account for the heaviness and struggle inherent in her painting, is the fact that she emigrated from Israel as a teenager.

But she rejects a reading of her work as being a direct response to any one thing. She brings all of herself, including the fluidity of her sense of identity, to the studio every day. Rather than her paintings containing references, she prefers to think of references passing through her work. She encodes the paintings’ content, concealing it under layers, thus rendering it esoteric and deeply personal.

All images are Courtesy of Ameringer | McEnery | Yohe Gallery New York, Photography by Gene Ogami