This year’s 60th edition of the Venice Biennale, titled “Foreigners Everywhere,” curated by Adriano Pedrosa from Brazil, takes an in-depth look at the work of more than 300 artists and collectives who have experienced exile and colonialism. Pedrosa’s thoughtful selections for the main exhibition and strong representation of immigrant artists in the pavilions resulted in an inspiring gathering of underrepresented artists—less art world and more real world—with Indigenous perspectives and ecological concerns at the forefront. Reality seems to be taking hold in Venice.

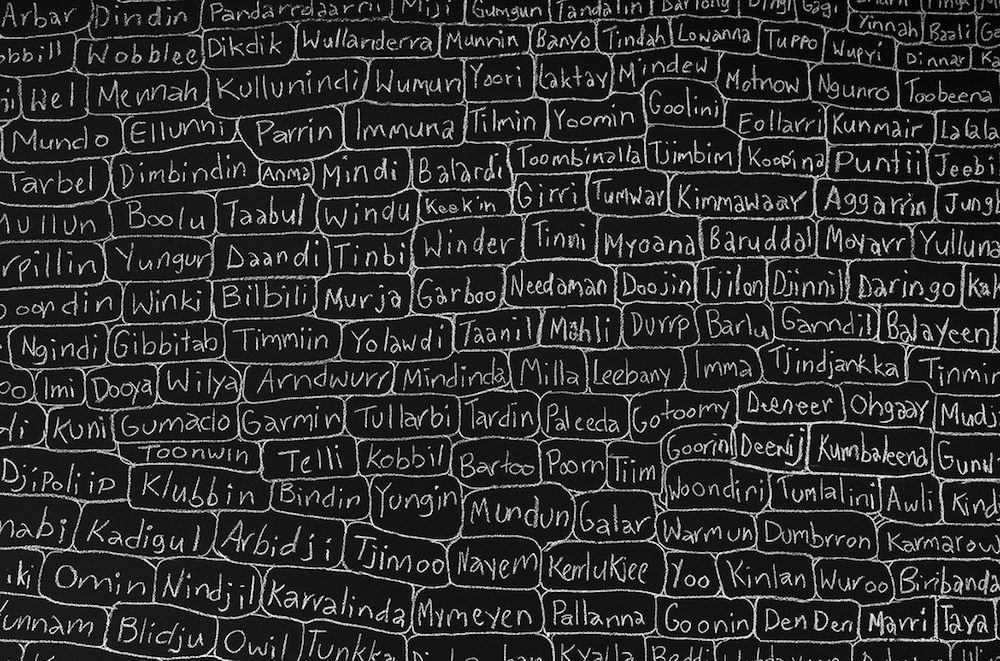

As we face colonial practices of genocide and displacement, with current wars in Ukraine and Palestine, the winners of the Golden Lion award this year were two Indigenous artists. For Best National Participation, the award was bestowed on Archie Moore, the first Indigenous artist presenting for Australia. His work, Kith and Kin (2024), is a monumental research-based installation—a genealogical mapping of 10,000 years of the artist’s ancestry. Unfortunately, the darkened space made it almost impossible to decipher the chalk-drawn lineage that climbed up the walls onto the ceiling, or the large table of documents and water below it. The winner of Best Participant, the Māori Mataaho Collective, representing New Zealand, installed a large-scale woven work made with gray-colored reflective hauling straps that mimicked patterns of customary ceremonial mats, or whariki takapau.

Jeffrey Gibson, the space in which to place me (installation view), 2024. United States Pavilion. Photo: Timothy Schenck.

This year’s US Pavilion also presented an Indigenous artist for the first time with a solo exhibition. Jeffrey Gibson, a Choctaw/Cherokee artist, staged a vibrant celebration of queer Indigenous pride, titled “the space in which to place me” (2024), a series of installations vibrating with historical facts and empowering statements, acknowledging a thriving culture. The artist decided to go all out with his bold style of colorful work that incorporates beading, fringe, giant totems and jingle dancers. Words that critique racism and hate were woven or coded within bright-colored triangles and diamond patterns in his paintings. As Gibson recently explained on a CBS Sunday Morning interview: “We’re still here. We’re not invisible. See me, see us!”

Indigenous artists and curators from across Turtle Island (also known as North America) were shocked that a review in The New York Times implied that Gibson went overboard with his work. Was the writer simply uneducated about Native American art, or were they sticking to an unconscious bias due to Biennale overload? Either way, old tropes and stereotypes about “primitive art” appear to be alive and well in the art world. Which leads to several questions about Indigenous aesthetics: Are all Indigenous artists supposed to make similar work? Should Indigenous art only be subtle and not colorful? Should the subject matter be only about painful experiences?

Indigenous people have a wide range of cultural aesthetic experiences related to ceremonies and community-making and are currently having their moment to express ancestral legacies through a contemporary art lens. There isn’t only one Indigenous aesthetic. That said, Gibson does feel it’s okay for people not to “get it.”

Sandra Gamarra Heshiki, Enlightened Racism I, 2024. Spanish Pavilion, Venice Biennale 2024. Photo: Eliza Goodpasture.

In the pavilion representing Spain, a country with a deep history of enslavement and displacement of Indigenous peoples and alterations of natural ecosystems and habitat, was Spanish-Peruvian artist Sandra Gamarra Heshiki, the first immigrant to represent that country. For “Migrant Art Gallery” (2024), she presented a museum-style installation, or pinacoteca, with six rooms providing thematic provocations that included Virgin Land, Cabinet of Extinction, Miscegenation Masks, Cabinet of Enlightened Racism, Dying Life Altarpiece and Migrant Garden.

In the garden courtyard of “Migrant Art Gallery” stood 11 human-sized statues painted on thick glass, which have symbolic power in former Spanish colonies, along with migrating plant species. A sitting figure, representing original peoples from Buenos Aires, Argentina (Tehuelches), has written on the verso, “Pachamama is the earth—the initial and final stage of life.” On the back side of a statue representing the Emberá Katio community in Bogotá, Colombia, is written, “Face-painting has nothing to do with concealment or the transitory restraint of individual identity. On the contrary, it constitutes an exteriorization of the self, which is considered beautiful.” Gamarra Heshiki’s immigrant perspective provides a counter-narrative that bravely addresses racism, sexism and migration.

Sandra Gamarra Heshiki, Pinacoteca Migrante (installation view), 2024. Spanish Pavilion, Venice Biennale 2024. Photo: C&AL.

Another pavilion addressed the traumatic effects of exploitation and resource extraction such as loss of forests and biodiversity—a powerful installation of 21 aromatic 3D-scanned and cast sculptures based on original smaller clay works by the Congolese Collective CATPC, artist plantation workers presenting for and in collaboration with the Netherlands. Titled, “The International Celebration of Blasphemy and the Sacred,” the works comprise figures of humans and animals cast with cacao, sugar and palm fat that represent stories of the devastating impacts on the Congo by Belgian colonists, where plantation workers died as enslaved people. The collective has been buying back their ancestral lands and transforming them into biodiverse agroforests from the sales of the sculptures, which are symbols of acknowledgment and repair.

Brazil’s Pavilion exhibiton, titled “Ka’a Pûera: we are walking birds,” included contemporary Indigenous ceremonial works created by the Tupinambá Community of Serra do Padeiro: a feathered cape, along with 12 empty stands representing mantles that have been collected by museums in Europe—yet to be returned to Brazil. The installation sets out to address the problematic issues of colonization with the capoeira, a small bird that lives in the dense forest, as a symbol of Indigenous resistance.

The past two Biennales have offered works that address our ecological fate and have included Indigenous voices. As we deconstruct colonialism, our love of museums and the hierarchical art world challenges our ability to take off systemic blinders. The very institutions that fund and present this work today are questioning their function and fate. We stand on the edge of unlearning everything we know. We need an art that speaks to our humanity. The 60th Venice Biennale is the work of our time.