While it would not be incorrect to say that Kenton Parker’s work primarily deals with nature, it would be rather misleading. There are no polite painted landscapes or photographs of waterfalls or mountain ranges. Cement, cars and trash are just as common as flowers and trees. Works that reference the natural world are complicated in their meaning, and, more often than not, are characterized by insouciance, foreboding and perverse fascination.

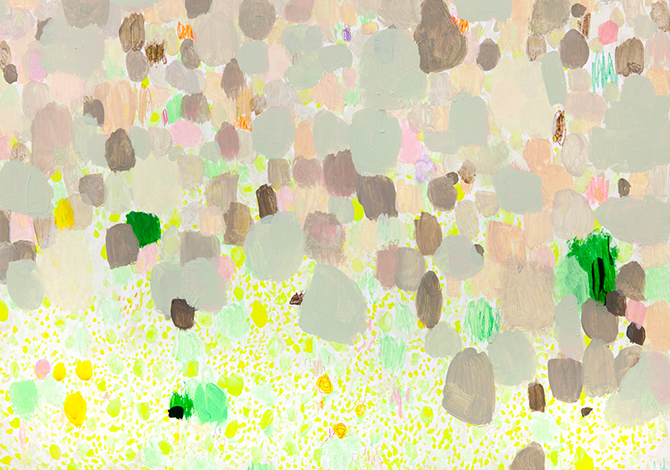

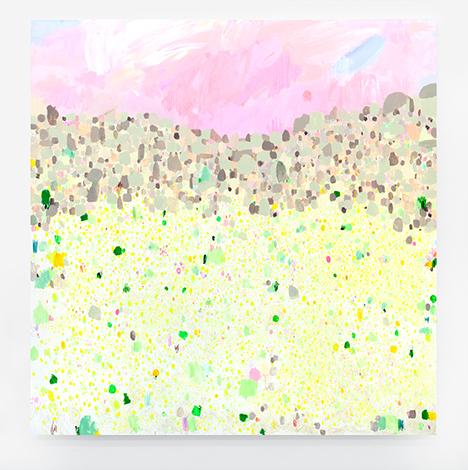

The four paintings in the gallery’s front room are expansive and straightforward celebrations of the flora and fauna of Los Angeles, Parker’s current home. In works such as Anouk and Everything Counts in Small Amounts (all works 2015), pristine white canvases are adorned with methodically-placed but ebullient daubs of paint in shades of cotton candy-pink, grass-green, and golden yellow; some marks resemble Cy Twombly scribbles, others shimmering splotches akin to those of Sam Francis. These Arcadian works are joined in spirit by two smaller black canvases, Catching a Ride on a Shooting Star, Be Back Real Soon and The World is Yours, upon which white chalk marks of delicate pinwheels and fireworks give off a celestial vibe. All of these works may indeed be pretty, but the obsessiveness of Parker’s mark-making somewhat belies their appearance of casual serenity.

The other works in the show contrast the openness of the natural world with interior spaces much more isolated and claustrophobic. Room with a View, a rundown tool shed covered in brittle palm tree branches and surrounded by dirt and detritus, fills the back room of the gallery. An empty rocking chair, moldering paperbacks, scrawled words, and rusted tools are discomfiting in their evocation of the uncanny; this is a hermitage à la David Lynch, not a peaceful hideaway.

Behind the shed is another confined space. Between the window and a low wall, this fort is covered with blankets that, lifted up, reveal a small space to sit and watch Parker’s video, To Infinity. Another and very familiar closed space is the subject—the inside of Parker’s car. Ray Bradbury’s short story “The Pedestrian” comes to mind, with its line “In ten years of walking by night or day, for thousands of miles, he had never met another person walking, not one in all that time.” We see the view outside the driver’s side window as Parker sometimes zooms, sometimes slows to a crawl along the Los Angeles freeways.

There’s a bit of Baldessari in the monotonous chronicling of the cars passing by, but the upbeat music of Depeche Mode, Queen and Coldplay mitigates the mundanity. Occasionally we see the faces of Parker’s vehicular neighbors glance over at him curiously, which almost gives the impression of a violation of privacy. The cloistered world of the car, which denizens of Los Angeles are particularly familiar with, is an extension of our self—an inviolable sanctuary of steel and glass that moves us through time and space. In the car—or shed or fort—one is anonymous and alone with one’s thoughts, which may just tend to the impious.