Your cart is currently empty!

Jason Rhoades at Hauser & Wirth

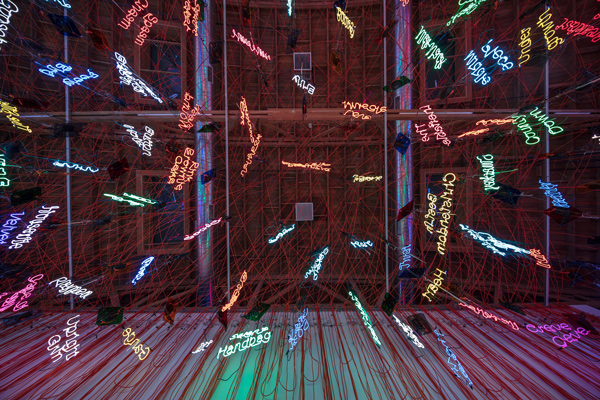

It’s true what they say. You can’t go home again—even if home is a neon jungle. Even if you’ve remade that neon jungle into your own constantly morphing, expanding universe. Even if that jungle is based upon an ideal garden of your youth, into which you’ve sown every idea, image, metaphor, concept, or obsession that ever flew into your head, and seemed to take a shape one could physically reconstruct.

Jason Rhoades was having a real LA moment at the time of his death (2006), here in the city he made his home base—although he was reluctant to affiliate with any galleries here. After making an enormous splash at UCLA; being featured in a couple of group shows; and producing what was only his second solo gallery show, Swedish Erotica and Fiero Parts, specifically for the Rosamund Felsen Gallery; somewhere between his participation in a group show in Ghent (Piece in Ghent, or PiG) and the 1995 Whitney Biennial, European art centers had become his default exhibition terrain. He would continue to show regularly with David Zwirner in New York throughout his life; but his collectors were mostly European, and he professed to have little interest in LA collectors. He thought L.A.’s gallery scene was caught in the position of competing for attention with the Hollywood film and television industry—a perspective perhaps shaped paradoxically by the insularity of his studio operations and his simultaneous avid consumption of Hollywood entertainment.

He had a point about people in LA wanting to “get it” faster; a need to close the deal on a discussion or examination. “When it comes down and deals with real life, Americans just hate it. They don’t want it to… come down and mess up the floor, or mess with your life. They don’t want to have to smell it.”

It would be reasonable to assume that the physical and narrative sprawl of a Rhoades installation might be something most people in LA, including its sophisticated fine arts audience, would have limited patience for—though you wouldn’t guess that from the crowds streaming through the six-installation Hauser & Wirth show since February. Or at least they don’t mind messing with the floor if all they have to do is recline or tread softly upon its (carefully) scattered towels, as in one of the installations reconstructed here, My Madinah. In pursuit of my ermitage… (2004), which yields something of a meditative moment in an otherwise cluttered and information-clotted exhibition. (You can pick out a mantra from among the 240 slang terms for female genitalia in neon overhead.)

Within the fairly open-ended and always veering-on-the-chaotic domain of Rhoades’ practice, the show is surprisingly controlled. The scale of the galleries might be a factor—the installations don’t squander a square inch. Rosamund Felsen remarked in a phone interview that Swedish Erotica looked only a third its original-size—and not quite “Ikea” enough; which may have something to do with the fact that at least a third of it is in private collections (the rest being held by MOCA). But where the slightly downscaled installation skimps Ikea, it emphasizes DIY eccentricity reminiscent of Oldenburg and, in extreme contrast to the rest of this elevated-testosterone event: vulnerability.

My Brother/Brancuzi (1995) may be closer to the original dimensions of Rhoades’ Whitney Biennial installation (to judge from photographic documentation) and is similarly controlled, even contained. But then its inspirations are actual rooms: his brother’s room (a converted garage) and the studio of Constantin Brancusi. We don’t exactly have to “smell it” here, either; but we can imagine what that might amount to from Rhoades’ photograph of the room. This is a man cave. The paneling looks faux and is probably chemically treated; the aquarium against the rear of the wall is dominated by a large white mass of dead coral and looks to have seen better days. The center of the room is the place from which to survey its contents and dream up new stuff to build or buy.

Rhoades reverses the man-cave conventions and instead of arranging its contents against the walls, pushes everything to the center, leaving the walls to a clean, gallery-like array of photographic documentation, and foregrounding the man-cave fantasies: in particular, a mini-donut machine cranking out endless mini-donuts—racked up and spilling off a spindle to mimic one of Brancusi’s Endless Columns.

Between Piece in Ghent and My Brother, Rhoades effectively lays out a scheme for his life’s work—which he himself regarded as a quasi-continuous (and never finished) project: a closed circuit comprising the voyage out—to marketplace/sacred space (which, true to the rules of the art game, Rhoades conflates), and the voyage home.

You could call it an infernal combustion machine.

Utility imposes its own formalism in this world. The industrial 5-gallon bucket is both receptacle and pedestal. Vehicles are important in this universe—carts and trucks, mini-bike, motorcycle, automobile. (Rhoades wasn’t particularly interested in mass transportation. He needed to be in his bubble.) Rhoades frequently spoke of shopping as a “sculptural gesture,” but the sculpture (or reconstruction) happened in the studio. He was interested in the random intersection that took him down a different aisle. Or road; or stream—of consciousness. Even the fetish objects—dream-catchers, and the like—partake of this transit motive. He’s dredging the moist beds of dreams and fantasies to incorporate them into his personal mythology.

It sounds grandiose and of course it was, though I don’t think this was necessarily Rhoades’ entire intention. He had to take apart the engine to see how it worked. He was trying to extract meaning from each part of it: harvest, display, shopping, unwrapping, re-assembly. But this, too, was intended to be somewhat random—independent of whatever meaning (distinct from sheer utility) had gone into it. (Felsen speaks of Rhoades’ process, his “phenomenology” as being a fundamental aspect of his legacy.)

“Disposable” was almost an ideal state. “I really like consuming the latest model of disposable technology… I think most shows should be ‘Just Do It’ [after the Nike trademarked commercial slogan] shows. It would be much more interesting and you wouldn’t have to worry about moving these things around and insuring them.” It was unsustainable; and Rhoades knew this, too.

Before he decided to bring it all back home, he crossed a number of such intersections—at fairs, museums, in Switzerland (he had met Iwan Wirth before he attended UCLA), and at Zwirner. Art fairs worked for Rhoades. “Art fairs were just getting bigger and more competitive, and Jason had a read on that,” artist Richard Jackson, Rhoades’ mentor and former UCLA professor, recalled in a phone interview. He also enjoyed the “party truck” atmosphere. “They’re going to be around and we just have to figure out how to fuck them up,” Rhoades told him. His business savvy and 4-H upbringing worked for him, too. He understood what would work in the designated spaces, and how to finance it. Zwirner, Wirth and various collectors underwrote substantial production budgets.

The Black Pussy… and the Pagan Idol Workshop (2005) had grown out of works previously executed for Zwirner and Hauser & Wirth, similarly obsessed with the Islamic holy sites of Mecca and Medina, and the journey of commerce conflated and commingled with the notion of pilgrimage and sacred ceremony. Unlike the layered (and slightly Rube-Goldberg-esque) cosmology of, say, The Creation Myth (1998), Black Pussy presents what seems to be an unending and interwoven—or just piled on—series of devotional invocations and digressions. In addition to the industrial/restaurant racks, the ceramic carts and donkeys, we have the aforementioned dream-catchers, hookahs, Gongshi or scholar’s rocks, real beaver-felt cowboy hats, and of course idols—or what will serve for them. Walking through (or around) it, what it actually feels like resembles a cross between a souk, a Tangier brothel, and Koontz Hardware in West Hollywood.

Mastering the shopping experience is a useful asset when you want to attract the 24-hour party people in LA. Although Rhoades was serious about bringing interested outsiders into his Filipinotown studio to fuck with his personal Kaaba, idol workshop and cosmological curios, he was cautious. He clearly wanted certain dealers, collectors and receptive museum curators to see it. But—always a control freak—he was cautious about admitting “critical” eyes. Alex Israel was brought in to curate the guest list as well as help organize the performance entertainment.

The Hammer Museum had already plunged in with a commission for the following year that would never be completed. Others were less receptive to the direction Rhoades’ work was taking.

Or conceivably simply exhausted by what a long strange shopping trip it had been. By the summer of his death, though, invitations to his “Black Pussy Soirée Cabaret Macramé” were much coveted. The evenings achieved the status of legend.

Ten years later, it all seems too much and not enough. Rhoades understood that the constituent pieces of an installation, however imbued with their own layers of symbolism and interior narrative, had to function seamlessly within the “perpetual motion machine” he intended his assemblage/installations to be. Looking back, it almost seems as if he was inviting those friendly eyes and hands to rip out some of those seams and restitch the subsidiary narratives and subplots. Alternatively, he might simply have edited, reined it in a bit—but by that time Rhoades had himself become a kind of perpetual motion machine.

Rhoades never quite made it home (though in a way he came awfully close—consider, e.g., Sutter’s Mill (2000) of his larger Perfect World project, the dual innocence and sophistication of Creation Myth here). The end is never pretty; and perpetual motion must inevitably give way to maximum entropy. In retrospect, Rhoades was deflected by the same market forces (demanding and well-capitalized dealers with committed collectors) that empowered him to indulge his obsessions and narcissistic fixations. Rhoades was reaching for a kind of transfiguration of the profane and polluted beyond the neon jungle; but as Van Eyck could have told him, that kind of redemption is costly.

“Jason Rhoades Installations, 1994–2006” at Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles, ends May 21.