Entering James Hyde’s show at Luis De Jesus, one immediately wonders: What sort of pictures are these? At first glance, it is difficult to determine whether the expansive images are manual or mechanical, painterly or photographic.

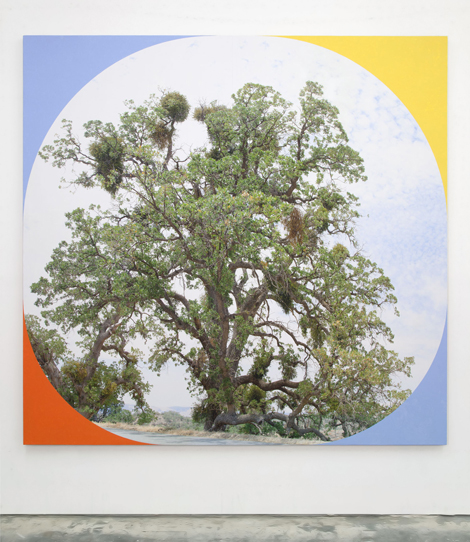

Materially, they are hybrids. Each canvas is inkjet-printed with one or more intricately detailed landscape photos that are subsequently covered, divided and framed by abstract hand-painted curves and circles suggestive of Minimalist and Color Field painting.

As a mode of representation, photography is commonly privileged over painting. Withal, painting purists eschew the idea of combining traditional pigments with photos or other mechanical technologies. In splicing painting and photography, Hyde challenges dualistic notions that pit one against the other. Yet his larger goal is to expand the scope of painting. While his pictures technically occupy both realms, the artist maintains that they are paintings. The exhibition’s innuendo-laden title, “Ground,” is partly a reference to Hyde’s use of photographic representations of terrain as substrates for painterly gestures.

In Axis and Coordinates (both 2015), oak trees inhabit lens-like globes whose forms are delineated by the rectangular surfaces’ painted corners. There, painting frames the photos rather than photography framing ways of thinking about painting. The tree in Axis is upside-down as though projected via camera obscura.

This is the Brooklyn-based artist’s first Los Angeles solo exhibition since 1997; and his painterly investigations and California landscape photographs dovetail with themes of temporal and locational separation. Photographs are flat reproductions, whereas paintings are tactile traces of physical action. Hyde’s brushwork is palpable in subtle strokes, blebs and tiny hairs. Four stacked aerial landscapes in Ripples (2014) evoke the feeling of looking out of an airplane sequentially over time; black-and-white arcs become sections of a giant window.

As opposed to photographic lenses, side-by-side circles in Locations (2014) and arcs in Font (2015) seem ocular. The fault-like slippage between mountains in Locations could refer to variances between places and memories. Between the two arcs in Font, a new meadow kaleidoscopically forms around the seam of abutting landscape photos, similar to the way stereopsis makes sense of parallax.

In the adjacent gallery, Alexi Worth’s concurrent show, “Surface,” is equally worth seeing. Like translucent photograms, four paintings on nylon mesh exhibit perplexing layered arrangements of flat, simple forms whose idiosyncratic surfaces imbue them with a strange luminosity. The two exhibitions complement one another, lyrically intertwining binaries while exploring relationships between painting, photography, and perception.