“Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirrors” at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, DC, is an ambitious show by any stretch of the imagination, boasting six of Kusama’s Infinity Mirror Rooms together with a selection of other work from the remarkable 65-year career of the “world’s most popular artist” (according to a 2015 survey on museum attendance by The Art Newspaper).

Kusama has achieved such a level of fame that timed passes, which are free, are required to visit the show. Demand for the passes is high and they’re snapped up as soon as they are released.

While the work is extraordinary, the exhibition was not entirely satisfactory. This was not the fault of the Hirshhorn by any means, but rather the nature of Kusama’s work, which makes it challenging to show in this kind of large-scale, public exhibition. Because of the size of the Infinity Mirror Rooms and their enormous popularity, visitors must wait in line for anywhere from 15 to 20 minutes to get in to see them in groups of two or three, only to be shooed out after 20 or 30 seconds depending on the room. This gives a real stop-and-go quality to the whole affair and the experience of waiting in line ends up overshadowing the art. Another problem is that the crowds are so intent on seeing the Infinity Rooms—and really, who can blame them—that the other work by Kusama, her glorious dot and net paintings and her fierce little works on paper, are largely ignored.

Yayoi Kusama with recent works in Tokyo, 2016, photo by Tomoaki Makino.

As most everyone knows by now, Kusama suffers from a profound obsessive-compulsive disorder and has chosen to reside at a mental institution, where she was first committed in 1975, spending her days in one of her two nearby studios.

Kusama’s art is both an embodiment of and therapy for the peculiar hallucinations that have visited her since she was a young child living in war-torn Japan. It was then that she first experienced the hallucinatory “flashes of light, auras and dense fields of dots” that would provide the portal to her creativity and that she would co-opt for her art. Nowadays, at age 87, she is doll-like, with candy-apple-red wig and strikingly original clothes in patterns of her dots and nets.

Pumpkin, 2016, at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, courtesy of Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo/Singapore, photo by Cathy Carver; ©Yayoi Kusama.

Kusama’s simple shapes, bright colors and humor are very much in synch with that of a child, though the obsessional nature and focus on self-obliteration underlying the work is anything but childlike. Over the years, the dots have reappeared in many different versions, including the pinpoints of light in the infinity rooms. In two paintings at the Hirshhorn, Accumulation of Stardust (2001) and Dots Obsession XZQBA (2007), the dots have evolved into three-dimensional orbs. As the title of the first painting suggests, she’s combined two directions of her art, marrying together visually her flat polka dots with her “Accumulation” sculptures. Accumulation of Stardust is a showstopper that gives the infinity rooms a run for their money. Sumptuous and hypnotic, the work’s rich red with its curious tonal modulations and the wall-to-wall quality of the beaded pattern of dots creates a stunning effect that commands attention from across the room. Dots Obsession XZQBA, a monochromatic work in shades of gray, could well be Kusama’s “Rosebud,” referencing as it does those long-ago stones by the side of the river.

There are a number of versions of Kusama’s net paintings. These works, which Kusama produced in round-the-clock marathons, lasting upwards of four days, are meditations on repetition and infinity. One is drawn to Infinity Nets Yellow (1960) and No. Green No. 1, (1961) on account of their luscious color, and one lingers in front of them to admire the patterns created by the repetitions. You can see how painting them as obsessively as she did would cause the nets to migrate off the canvas onto objects in the room as Kusama has described. These particular hallucinations inspired her to make sculptures. No I.Q., (1961) features the reverse image of the net. Though smaller than the others, the painting, with its raised undulating pattern of netting, stands out. These paintings, as well as her works on paper and the “Accumulation” soft sculptures, all have an appealing raw earthiness that is quite different from the slick aesthetic of the Infinity Mirror Rooms and the large-scale polka dot installations.

Infinity Mirror Room—Phalli’s Field, 1965, in Floor Show, Castellane Gallery, New York, 1965, photo: Eikoh Hosoe.

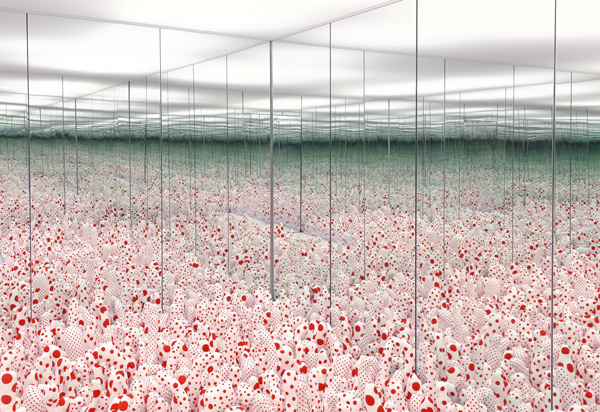

The Mirror Infinity Rooms do not disappoint. The earliest, Phalli’s Field (1965) features a multitude of red polka-dotted soft-sculpture phalluses “growing” out of the floor. Kusama has said she began making the shapes to help conquer her fear of sex, a result of being sent as a young child by her mother to spy on her father’s sexual assignations.

In other rooms, Kusama uses colored lights that the mirrors multiply into endless constellations. Being inside, surrounded on all sides by the lights, is exhilarating. You’re gobsmacked by the effect of these glowing jewels of light, or flickering “candles,” and the sense of the infinite that is present inside. You’re also a little unsettled, shut up in this small space that contradicts the sense of vastness it conveys. You begin to lose your bearings and your sense of self, immersed in the installation. It’s clear, even in the mere 20 to 30 seconds you’re allowed in one of the Mirror Infinity Rooms, that what you’re sensing is the obliteration of self that is central to Kusama’s philosophy.

The Self-Obliteration Room (2002–present) is the final room in the show. Arranged like a domestic interior, the space is appointed with furniture, items of clothing, bookshelves, a piano, all of it painted white. On entering, one is handed a sheet of brightly colored stickers to place anywhere in the room. This audience participation harkens back to Kusama’s art happenings. But it’s much more than that; in this room which is slowly being obliterated by dots, we see what Kusama is intent on doing with her art and also, we get a glimpse of what her hallucinations are like.

The Obliteration Room, 2002–present, collaboration between Yayoi Kusama & Queensland Art Gallery, photograph: QAGOMA Photography, © Yayoi Kusama.

Kusama began painting when she was eight. She attended art school, but enrolled as an escape from home and rarely went to class. As a young artist in New York, Kusama did it all: painting, sculpture, installation, performance. This was highly unusual. At the time, artists tended to stay within their chosen discipline. Over the course of her career, Kusama has been extraordinarily prolific, making, in addition to painting, sculpture and installations, avant-garde fashion, a film entitled Kusama’s Self-Obliteration—which she directed, starred in and produced—and 200 happenings around the world. As if her achievements as a visual artist weren’t enough, she has also carved out a significant career as a writer since returning to Japan, publishing numerous novels and works of poetry that are highly acclaimed.

Though their work is very different in execution and appearance, Kusama shares a potent kinship with the visionary artist Henry Darger. Both outliers, they each experienced traumatic childhoods—in addition to the war, Kusama was burdened with a violent mother who beat her—and each of them created an alternate reality that they could escape into and safely inhabit. Their obsessive approach and prolific output reflects the dire nature of work that is, in every sense, life-saving.