The center of the Los Angeles Philharmonic’s Friday evening program was a shimmering pulsation of musical color, both harmonic and timbral, in a field of black and white. Both Susan Graham’s rendering of a suite of Kurt Weill songs and Esa-Pekka Salonen’s own suite for full orchestra, Foreign Bodies, also conveyed a sense of the almost schizophrenic tension that carried through the entire program—the alien presence within the cozily familiar, the vernacular within the poetic, excitation mingled with anticipated regret.

There were certainly ‘black-and-white’ notes here, too—the raffish/Runyonesque (albeit German) gangster story behind “The Song of the Big Shot” (‘hard nut’ in the German expression—with lyrics by Brecht), songs from Lady In the Dark (with lyrics by Ira Gershwin) that evoked a black-and-white Manhattan of the 1930s and 1940. But there were amber hues, too (September Song), the syncopation of “I’m A Stranger Here Myself,” and the blues-y color of “The Saga of Jenny.” The songs were a kind of time capsule, but a richly reverberant one; and Graham was clearly enjoying this meander through a slice of Broadway history that somehow bridged chasms of emotion and time.

In its broad orchestral plan, Salonen’s Foreign Bodies offered a foretaste of the Varèse Amériques that would close the evening. (The percussion requirements for both compositions were both daunting and strikingly distinct—e.g., Thai nipple gongs in the Salonen; sleigh bells and, uh, ‘lion’s roar’ in the Varèse.) Chimes and percussion led off, with trumpets and broad brass lines giving way to more articulated figures in woodwinds and vibes. Violin tremolos lead into massed string episodes which segue back to flute and winds.

You practically felt the ‘winds,’ as if Salonen were waving his conductor’s baton over a field of wind-swept wheat, with parallel chromatic/harmonic changes registered between strings and horns. The music swung between a farandole-like figure in the horns and ethereal but arresting foreground lines in the winds and strings. The third movement (“Dance”) seemed to evolve these motives rhythmically and metrically with horns variously competing and underscoring other orchestral textures, some of which only faintly registered while others resounded with near ferocity.

There were textural (and certainly percussive) parallels between the Salonen and the single-movement Amériques of Edgard Varèse, but the works could otherwise have hardly been more different. Where Salonen’s work builds a kind of machinery of dance, Varèse builds what can legitimately be called a soundscape, a prototype for music (including electronica, film scores and ‘sound art’) being composed today. The score (there we go—no?) begins almost insinuatingly—a quiet line that might be nothing more than a meditation. (It is, for all its crashing dissonances, a meditative work.) But it moves efficiently forward, in crescendoing, ascending lines in trumpets and percussion, before settling again in the flutes and woodwinds.

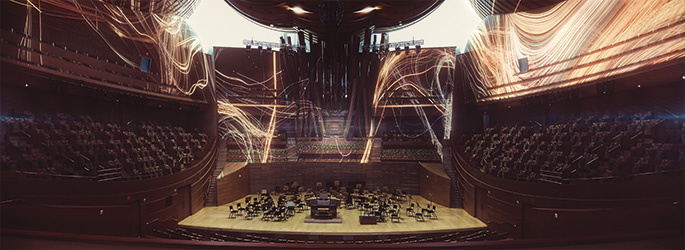

We were primed for what began to crescendo physically around us in the hall (in a sense delivering the impact we felt missing from the Herrmann suite from the Alfred Hitchcock film, Psycho, that opened the evening’s program). It would have been one thing to construct a film or video for the two-dimensional screen; but what the video artist, Refik Anadol, essayed here was a visual interpretation of the architecture of the music onto the architecture of Disney Hall itself. This was not a literal three-dimensional mapping of the score; and the effects here were variably two- and three-dimensional; but they did succeed in paralleling, to some extent magnifying it, enveloping the audience in this echt-urban soundscape. The video passes (with the score) through swirls and eruptions of motes, molecule-like chains, fibres, sand or snow into fluorescing grid-like formations, in turn giving way to prismatic geometries, evolving and devolving like chambered shells and coral reefs. In certain passages, it made me think of some of the imploding urban blocks in Christopher Nolan’s 2010 film, Inception. The machinery and mechanicals gradually morphed back into the comets and shooting stars with which it began. Throughout, there were sly references to the physical production of the music itself (e.g., the conductor’s silhouetted moving figure).

It can be argued whether or not these elements—Anadol’s exploding and imploding blocks–adequately served the ‘blocks’ of the Varèse score, which tumble and pour at us episodically with spare (if any) musical development or elaboration. (There are ‘bits’ here reminiscent of everything from Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring to Bruckner to Gershwin and jazz and sirens and jackhammers.) But as ‘music drama’—sheer sight-and-sound spectacle—I thought it remarkably effective. What was most telling was the contrast with the music that began the program. The score for Psycho is one of the most superb Bernard Herrmann ever wrote; and was superbly played by the Philharmonic’s strings on this particular evening. Even so, you felt its impact diminished by the film’s absence. That was part of the essence of its collaborative genius (and contrary to the ridiculous program notes, Psycho—shot for shot one of the greatest pictures ever made—would never have been “relegated to footnote status”): Hitchcock and Herrmann each ‘signed’ the other’s work.

It can be argued whether or not these elements—Anadol’s exploding and imploding blocks–adequately served the ‘blocks’ of the Varèse score, which tumble and pour at us episodically with spare (if any) musical development or elaboration. (There are ‘bits’ here reminiscent of everything from Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring to Bruckner to Gershwin and jazz and sirens and jackhammers.) But as ‘music drama’—sheer sight-and-sound spectacle—I thought it remarkably effective. What was most telling was the contrast with the music that began the program. The score for Psycho is one of the most superb Bernard Herrmann ever wrote; and was superbly played by the Philharmonic’s strings on this particular evening. Even so, you felt its impact diminished by the film’s absence. That was part of the essence of its collaborative genius (and contrary to the ridiculous program notes, Psycho—shot for shot one of the greatest pictures ever made—would never have been “relegated to footnote status”): Hitchcock and Herrmann each ‘signed’ the other’s work.