Margie Schnibbe has a jungle thing going on in the front reception area of her house, as it seems to be filling with artsy-crafty sculptures made of stuffed pre-dyed and hand-painted fabrics. Some of them have a vaguely Nikki de Saint-Phalle aspect; others could only be the winking ironic craft creations of Schnibbe herself. What looks like a large seven-foot high patchwork dildo dominates a cluster of such objects.

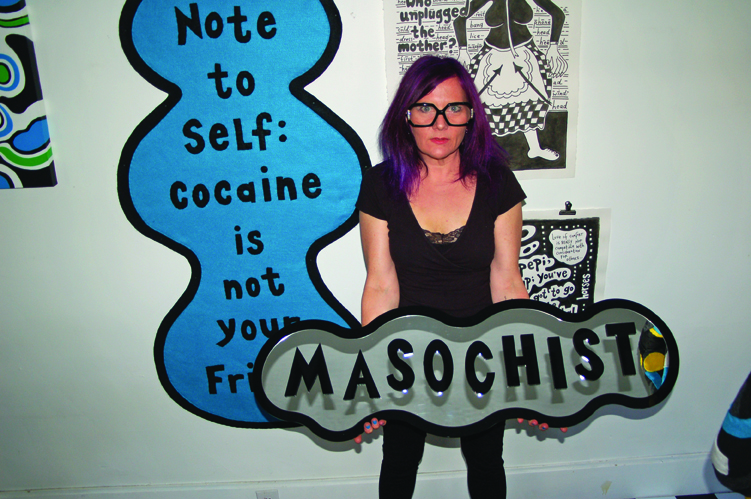

On one wall hangs a vintage Schnibbe text painting in her trademark schoolchild-doodly script: “Note to self: cocaine is not your friend.”—the words descending vertically in an undulating text bubble. A couple of other older drawings hang nearby.

Just below is a table strewn with zines and books, a couple of which instantly stand out—a copy of Krafft-Ebing’s Psychopathia Sexualis—a book I haven’t set eyes on since my school days; and a small volume by Wayne Koestenbaum—Humiliation. I’m impressed when I flip open the cover to see that it’s personally inscribed to Margie “with deepest respect.” I leaf through a zine and my eye falls on a photograph of a man I know to be the poet and curator, Frank O’Hara, alongside a text I also know with certainty he could not have authored. Schnibbe explains that it’s one of the contributions to a zine produced in conjunction with one of Darin Klein’s “Queer Pile-Up” performance/exhibition events. There are also a few proof pages or test images of iPhone screens—snippets of dialogue that start to make a kind of silent noise of slightly off-kilter, non-sequitur or discontinuous narrative. It’s a remarkably resonant table, like most of the surfaces decorated with these variously bubbled and mosaic-fragmented texts.

Amid the free-association pile-up in my brain, It occurs to me that Schnibbe has a new “thing” going on with these iPhone screens, as the images and pages crop up elsewhere in this and other rooms; and indeed they are at the heart of her upcoming show with Charlie James in Chinatown, the theme and title of which is “Hooking Up.” Taking in the variously bubbled text paintings and drawings, some familiar from previous shows (even going back as far as a show I reviewed for these pages), it dawns on me that Schnibbe has been “texting” in one sense or another for a significant part of her career. But as we walk around her house/studio, I realize that it’s all of a piece with a general borderline obsessive-compulsive modus operandi. The way some people compile lists, Schnibbe compiles dialogues—with family, friends, peers, random others, and herself.

Innocence and pathology (or maybe just prurience) stand in close proximity here — in both the work and the array of domestic objects, books and magazines, and décor. Among other things, Schnibbe collects old mass-market paperbacks of mid-20th century vintage (the kind that breathed fresh fetish into Richard Prince’s nurse paintings); and she displays a choice handful of them with their vividly graphic kitsch cover art on the upper walls of the room where she keeps her flat files. I’m intrigued to see an English edition of Colette’s The Last of Cheri among the more predictable hard-boiled mystery and thriller titles.

Schnibbe pulls a couple of full-size painted images from the flat files, duplicating images I’ve just seen in the front room—one, a sequence of texts, alternating down the space of the blown-up iPhone screen, another with an image that might be called “still life with erect penis, thumb and Diet Coke.” The image is not photorealistic in the traditional sense, but seems to duplicate the imperfectly resolved pixelated digital soft focus of a smartphone screen. These are proofs that have recently arrived from China—where Schnibbe is having the full-scale paintings on canvas executed to her specifications.

I mention the seeming disconnect between the overexcited tone of some of the texts—e.g., “… I need to see God… ” or “Get to the door… ”—code to trigger an actual carnal encounter; and alternating graphic images no less explicit than the aforementioned “still life.” “I like that it’s fragmented… I find the distance really exciting.” And then—practically in the same breath—she says, “I like the fact that there’s a transcript of the conversation.”

As I’m considering the radio-script aspect of certain of these dialogues, she shows me a 10-page typewritten script taken entirely from a continuous text dialogue that became a performance piece. The performative aspect of her work has played out on a number of levels: in the real-life blur with certain external jobs she has taken on over the years (including sex work); in porn production and what might be called art-porn; in actual performance work which has taken place in various venues here in Los Angeles and elsewhere; and now, in private life.

Although Schnibbe may find the distance most exciting, she has not shied from taking the climax “to the door.” But there is still another, generational distance in some of the physical encounters with her “s-exting” partners, inadvertently casting her in a “cougar” role—which took me back to that Colette paperback. There are a lot of “Cheri’s” in Schnibbe’s life lately.

We cross the entryway to what is now apparently an office, decorated with among other things, about a thousand tiny ceramic sake or espresso cups—the products of “serial hysteria,” she claims—so she can show me some performance videos, including some very early pieces. Referring to one such early performance, she shows me an online link to both the piece and a poem it has inspired—by Wayne Koestenbaum. I tell her this places her amongst some rather exalted company—e.g., Anna Moffo, Jacqueline Onassis. Then I realize that Koestenbaum is addressing the same abject place Schnibbe locates in a cloud-shaped mirror directly across from us. Upon it, a single word: “masochist.” Krafft-Ebing would have called it paraesthesia. But as the sexual jungle turns into a “queer pile-up,” it’s probably a good time to remap the topography.

See Margie Schnibbe at Charlie James Gallery, Los Angeles, June 15–July 20, 2013; for more info: cjamesgallery.com

Above: Margie Schnibbe in front of her artwork at her studio in Silver Lake,

Photo by Lynda Burdick