When I heard the title of Jose Dávila’s recent book, Daylight Found Me with No Answer, it sounded familiar. During the years I was living in Guadalajara, I frequently talked with Dávila and other mutual friends at endless parties that lasted until dawn. But I hadn’t seen Dávila since those distant days and this was the first time I had ever paid him a studio visit. He was finishing a public project to be presented this fall at Los Angeles Nomadic Division (LAND).

Jose Dávila Portrait

His studio is located on Colonia Artesanos in downtown Guadalajara in a workshop neighborhood whose chaotic atmosphere signifies what many consider to be a specifically Mexican aesthetic. Daylight Found Me with No Answer is also the name of a Dávila sculpture made of twisted metal frames.

Jose Dávila, Daylight Found Me with No Answer, 2013. Metal frames and enamel paint, 550 x 250 x 270 cm., Courtesy of Galleri Nicolai Wallner, Copenhagen, 2015. Photo: Alejandra Jaimes.

This area also features many colonial churches (a couple of blocks from here there is even a church, El Refugio, right in the middle of Federalismo Avenue), dilapidated old houses with barred windows and central patios typical of early-20th-century architecture and streets lined with orange trees whose fruit nobody eats.

The façade of Dávila’s studio reveals only a number graffitied in purple, but when I cross the metallic threshold I discover an ample space with pieces made of rocks, concrete and glass. An assistant leads me across a patio filled with pots to a flawlessly kept library on the second floor, where I am given a refreshing glass of agua de ciruela amarilla. I am looking through the bookshelves when Dávila appears in a short-sleeve shirt, bermudas and white tennis shoes. He’s fresh from his honeymoon and the next day is his 43rd birthday.

Jose Dávila, Untitled (Duchamp), 2012. Archival pigment print, 174.8 x 133 cm.

Courtesy of Estudio Jose Dávila, Guadalajara, 2017. Photo: Agustín Arce.

“I’m very happy to make an urban sculpture in Los Angeles; it is something new for me,” he tells me while seated at a large wooden table in another huge space of this—I now realize—enormous studio. Here, under a two-sided roof, I can see one of his paintings (from the series “A Copy is a Meta-Original”), one of his cut-outs (Duchamp and his Fountain) and on a small piece of paper pinned to an office board is a geometric shape that gives me a first glimpse of what will become Sense of Place, his work at LAND: a cube, 2.40 meters each side, made of concrete, able to separate itself into pieces — as Dávila says, like a Tetris game. After a first exhibit as a complete cube in West Hollywood Park, the sculpture will then be deconstructed and each part will be taken to different places, both public and private, in LA.

“The idea,” he relates, “is that the pieces should present themselves in different contexts. Then, after eight months, they return and form the cube again. The cube will say something about how LA as a city is made up of many mini-cities.”

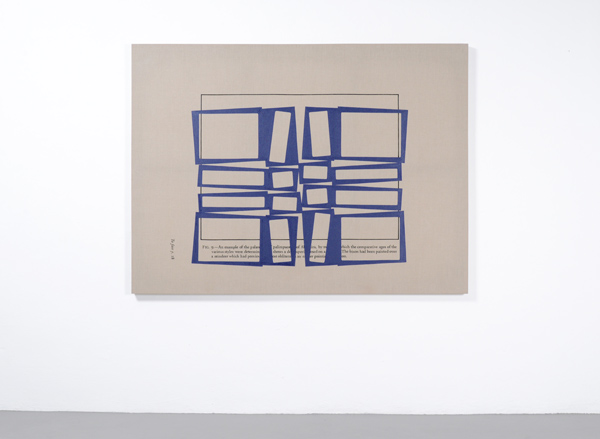

Jose Dávila, Untitled, 2015. Acrylic and vinyl paint on loomstate linen, 200 x 220 cm., Courtesy of Galería Travesía Cuatro, Madrid, 2015. Photo: Agustín Arce.

Jose Dávila, Truly A Difficult Subject to Express, 2016. Acrylic and vinyl paint on loomstate linen, 182 x 226 cm., Courtesy of Galleri Nicolai Wallner, Copenhagen, 2016. Photo: Agustín Arce.

Dávila’s fascination with squares and cubes brings me to suggest that Sol Lewitt is one of his main influences; he adds the name of Josef Albers.

Although Dávila has been drawing and sculpting since he was a sedentary child — he was born with cancer, and treated for many years in a Houston hospital—he decided on finishing high school to study architecture rather than art. The old-fashioned oil-painting classes at the public school of art didn’t appeal to him, and when visiting the faculty of architecture at a private university he was attracted to the layouts and models on display.

I suggested to Dávila that Luis Barragán, the award-winning Mexican architect, might have provided his introduction to art and that he would have discovered the work of Josef Albers when he visited Casa Barragán for the first time. “Yes, indeed,” he confirmed. “Actually there is a story I love about this Albers painting that Barragán had in the hall of his house, the yellow one (Homage to the Square, 1969). It isn’t an original but a copy Barragán made himself. I understand that Albers, knowing who Barragán was, wanted to give it to him but Barragán said, ‘Oh, no, thank you. I don’t need a gift, I only need your permission to replicate it.’”

Jose Dávila, The Bison Had Been Painted Over, 2016. Acrylic and vinyl paint on loomstate linen, 144 x 194 cm, Courtesy of Galleri Nicolai Wallner, Copenhagen, 2016. Photo: Agustín Arce.

In the absence of good art schools and galleries in Guadalajara, Dávila and his fellows of that time —Gonzalo Lebrija and Fernando Palomar—had an idea that grew as time went by. In 2000 they created Oficina para Proyectos de Arte (OPA), a space based on the 22th floor of the Condominio Guadalajara—a functionalist tower, the first skyscraper in the city, with a spectacular view of the four cardinal points. Many contemporary artists were invited to work there over the next decade. The Albanian artist Anri Sala made his notorious work No Barragán No Cry (2002) there, in which Dávila helped Sala to ride a pony by elevator to the roof of the building. “OPA was for me a kind of master degree or even a PhD. It was really what helped me to learn lots of things I hadn’t studied. As a self-taught person, helping other artists produce their work was a school in itself,” says Dávila.

Jose Dávila, The Lips Are Bright Crimson, 2016. Acrylic and vinyl paint on loomstate linen, 168 x 126 cm., Courtesy of Galleri Nicolai Wallner, Copenhagen, 2016. Photo: Agustín Arce.

Some years have passed since then and Dávila now has a workshop and a growing reputation with international projects like the one in LA. At a point in his career when he can move wherever he wants, I wonder why he chooses to remain in Guadalajara. “Guadalajara gives me time,” he replies. “I mean, when I have been in other cities like Mexico City, New York or London, I realized these cities are very time-consuming places. There is great culture on offer but it takes hours to get around. By contrast, here in Guadalajara it takes me 10 minutes to get from my house to the workshop. I have all the time I want. I’d like to quote John Baldessari when he was asked why he lives in LA. He said it was because it seemed so horrible to him. If he’d lived in a beautiful city like Paris or New York he wouldn’t have arguments to make about art. I’d like to apply this sentiment to Guadalajara.”

I mention seeing a photo of his at OPA. I recall that nobody appears in it—there’s just a table with three computers and that’s all. “We had nothing,” Dávila remembers, smiling. “The truth is that many times we only went over there to listen music for hours on end.”

See Jose Dávila at LAND, 9/16/17–5/27/18, nomadicdivision.org.