Of course I knew of bad-boy provocateur Alexander McQueen’s reputation as a brilliant couturier, with words like “artist” used to describe him, but such hyperbole is thrown about willy-nilly in the fashion world, and I just assumed it was an exaggerated way of saying he was really talented. “Savage Beauty,” the exhibition, which spans McQueen’s 19-year career at the Metropolitan Museum, changed my mind.

An unlikely fashion darling, McQueen triumphed in that difficult world by dint of hard work and amazing talent. But he never seemed dazzled by it all, maintaining a healthy cynicism throughout his career. Working class and overweight (he did eventually slim down), McQueen was also gay, which must have been a burden growing up in London’s tough East End. Thrice an outsider, McQueen developed within his steely self a rare empathy with the downtrodden and outcast and a richly honed perspective that made him constantly question the status quo.

There is no shortage of beautiful clothes showcasing McQueen’s renowned tailoring skill in the first couple of rooms. These are clothes with attitude, referencing S&M mixed up with Victorian romanticism. McQueen liked his women fierce and viewed his designs as a kind of armor that would shield and empower them.

It is in the room “The Cabinet of Curiosities” where things get really interesting. Here shelves and niches along the wall display some of McQueen’s more outré dress designs and various accessories, shoes and headgear he created in collaboration with jewelers and milliners. There are also videos of his fashion shows. These extravagant spectacles, with their bizarre take on beauty, enigmatic story lines and over-the-top garments and makeup, reminded me immediately of Matthew Barney, not in a derivative way, but in a parallel way. One dress with an anatomically correct lilac leather bustier atop a wide horsehair skirt, matching leather hood and horsehair “pony tail” was particularly Cremaster-worthy. Though I could find no paper trail connecting the two, I am sure they knew each other and were members of a mutual admiration society. McQueen collaborated early on with Björk, Barney’s wife, and both men, as part of their explorations into the nature of beauty, used the double-amputee model Aimee Mullins in their work. The beautiful carved wood boots McQueen designed for her (that many in the fashion world initially took for conventional boots, as opposed to prosthetics) are on display here.

Another dress, with a splatter design of paint, is exhibited next to a video showing its creation during a fashion show. Two robots shoot paint at the model as she revolves on a stand between them. Loaned by an Italian auto factory, the robots are sinister, Transformer-like with their wildly waving robotic arms — you can only imagine how nervous you’d feel sitting in the audience waiting for them to turn on you. Still another dress features a carved balsa wood skirt that flares out to at least four feet in back.

There’s a carved wood Chinese village headdress, which I imagine would be much like wearing a dollhouse on one’s head: a twiggy, upside-down nest of a “fascinator” composed of enormous porcupine quills and many examples of McQueen’s extreme footwear, including the notorious hoof-like clodhopper known as “the armadillo.” One of the real highlights is an incredible metal ribcage and vertebrae complete with curling tailbone. It’s a gorgeous piece of stand-alone sculpture. Seeing it as a kind of body art that someone would wear sparks an unsettling visceral reaction. I overheard one viewer remark: “It’d be tough going to the theater in that one.” I know she was making a joke, but she got to the crux of the matter. None of these items were really meant for public consumption; they were made for the runway and are part of the statement McQueen was making about his vision and himself. Yes, they were powerful marketing tools, and some may shy away from the overt commercialism that suggests, but they fulfill my criteria for art.

From a purely aesthetic standpoint, I think my favorite part was the Romantic Exoticism section, which featured extraordinary embroidery. At Givenchy, McQueen became exposed to the rarefied world of haute couture, embracing many of its techniques and tempering somewhat the fierceness of his designs. One beautifully tailored dress, a combination kimono and straitjacket, was particularly powerful, speaking volumes about fashion and its subjugation of women. Here too was a hilarious East-meets-West amalgam, a playful silk romper complete with an obi worn with American football shoulder pads and helmet painted with delicate Japanese designs.

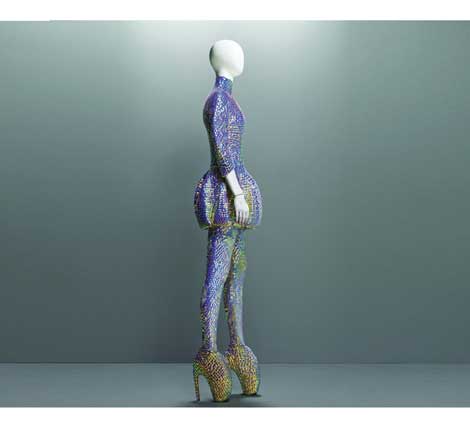

McQueen took inspiration for his shows from film, history, art, African tribal garb and nature. His Scottish heritage figured prominently in his work, in particular the centuries of oppression that occurred there at the hands of the English. McQueen incorporated feathers, horns, shells, bird skulls and caiman heads into his clothes, and in one of his final shows, “Plato’s Atlantis,” he developed a technique where digital images of animals and insects were woven into fabric.

One of his more provocative explorations of beauty and ugliness was inspired by a Joel-Peter Witkin photograph featuring a grotesque image of a fat, naked woman wearing a weird, fetishistic full-face mask and breathing through a tube. McQueen incorporated it into his 2001 Voss fashion show, which took place inside a giant mirrored box that reflected the appearance-conscious audience’s images back to them as they arrived. For the finale, the mirrored glass walls of a second box at the center of the room came crashing down, revealing a tableau vivant re-creation of the photograph. In this setting, where beauty had just been the focal point for the greater part of an hour, it must have been immensely shocking. It was pure McQueen. As he once said, “I don’t want to do a cocktail party, I’d rather people left my shows and vomited. I prefer extreme reactions.” But in this case, there was more to it than that, because it strikes me as intensely personal knowing McQueen’s own status as outsider.

McQueen was fascinated with death; morbid themes are constant in his oeuvre. Early on in his career, in a nod to Victorian funerary jewelry, McQueen included a lock of his hair as part of the label in each garment. At one fashion show in a church, he placed a skeleton in a front-row seat, and he topped an opulent ostrich-feather evening gown with a bodice of laboratory slides on which fake blood had been painted. What is remarkable about this dress, and all the rest for that matter, is that, despite these unorthodox materials, McQueen never sacrificed design or beauty, and so the end result is absolutely stunning. You’d never think the shimmering rectangles were anything but over-scaled pailettes unless you read the description.

The catalog accompanying the Met show features an eerie hologram on its cover, which changes back and forth between McQueen’s face and a skull. The catalog is unique in that photographer Sølve Sundsbø shot the garments on live models and subsequently manipulated the images to make them look like mannequins, complete with joints. There is a veracity to how the clothing looks on the body and an eeriness to the living flesh, supported by real muscle and bone, transformed into lacquered fiberglass.

One comes away from the exhibition very moved by the depth of McQueen’s passion, his incredible imagination and his pain. He was a fragile soul, committing suicide in February 2010, nine days after his mother succumbed to cancer and three years after his friend and champion, fashionista Isabelle Blow took her own life. McQueen burned with such intensity, producing two couture and two ready-to-wear lines every year, and presumably double that during his tenure at Givenchy; one feels he simply wore himself out. For McQueen, who was compelled to delve so deeply into his core for inspiration, the effort was enormously draining. Looking at his body of work, one is bowled over by the sheer beauty and creativity, but you can also clearly see the blood, sweat and tears writ large amid the satin and silk.

All images courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.