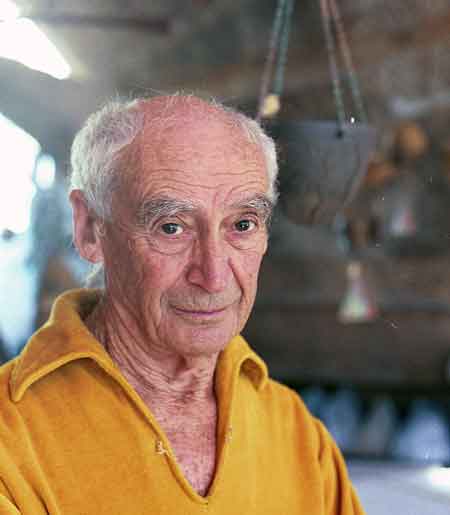

Paolo Soleri’s eyes sparkled from under bushy eyebrows, deep-set in a grizzled face; they projected intelligence tinged with a spark of irony. When I met Soleri (who died in April) the first time, back in 2000, he could at times appear weary, like a man called upon to explain his simple idea for the umpteenth time to someone who is having difficulty following. But the shadow of exasperation would quickly dissipate and once again he would patiently speak of his dream: the vision that was taking shape in the red earth of Agua Fria Canyon, halfway between Phoenix and Sedona.

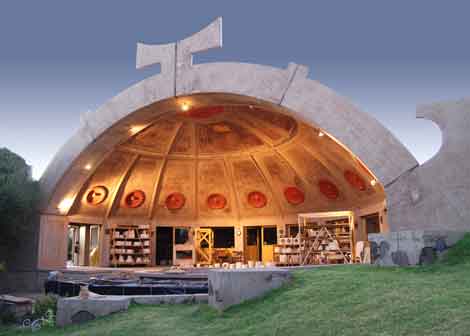

By the time I visited him in Arizona, it was apparent that Arcosanti, the city he had been hand-building in the desert, would never be completed. Not in his lifetime at any rate. But this did not stop Soleri, then 81, from scampering down the rocks to the bottom of the canyon to give a tour of the habitation prototypes he had initially built there with his students; concrete cubes strewn across the playa like toy building-blocks forgotten by a boy-giant. Like the imposing unfinished city up top, they were fruits of an unending passion for building and experimenting. For Soleri, erecting structures for living was a basic human compulsion, at once archaic, fundamental and ripe for revolutionizing. The passion he acquired as a student in his native Turin had brought him in the ’40s to Frank Lloyd Wright’s experimental studio at Taliesin West, and he had worked with the old man until his own strongly held views had led to an inevitable parting of paths. But the desert’s crystalline light and vast space had by then seduced the young Italian and so Soleri stayed on, opening his own studio: Cosanti, which he named by fusing the words “cosa” (thing) and “anti,” an implied endorsement of questioning conventional wisdom. Cosanti is still there—even though in the intervening years the Scottsdale suburbs have encroached on the desert where he first built earthen mounds, poured concrete over them and then dug out the dirt, leaving miraculous domes to float upon the land. This was the outpost where, between firing pottery and smelting bronze bells, he began to formulate his philosophy for building—an unconventional conception to say the least.

In 1967 he entered a competition for an airport in New Jersey with a design that would have housed the population of the entire state. It was an early example of hive-like city-buildings, massive structures that subsequently informed the idea for Arcosanti. Soleri was a prophet of density in the land of sprawl, capable of imagining the Western landscape dotted with city-states alighted on the desert like giant motherships, somewhere between Pueblo Indians and Star Trek; the Arcologies, as he called them, purported to reinvent cities from scratch. “I’m certainly not the first one to try that”, he told me then: “just think of the Roman legions, laying city grids as they conquered.” His notion of cities as physical embodiments of civic life was also a classical Greco-Roman concept, updated to his place and time. “What we’re trying to do here,” he would explain on the steps of the Arcosanti amphitheater, is “to offer American society an alternative to Los Angeles.” His brazen proposal was in fact to build in the American West cities as fabled and fantastic as the Tower of Babel, or the hanging gardens of Babylon: city-organisms inspired by a sort of superior natural order. “All organisms are three-dimensional and cities need to adopt that fundamental tenet of organic life. They need to reject the gigantism that is killing them, starting with the cars that push them into absurd horizontal dimensions.” The cure he advocated was the “implosion” of both cities and dwellings: “We need very small houses instead of ever bigger ones” he would exclaim, making his point. “We need miniaturization!”

Paolo Soleri was a great utopian dreamer in the vein of Gaudi and Sant’Elia, visionaries most of whose visions were destined to remain unbuilt. He abhorred the ubiquitous preening of “fashionable” architects and referred to their multimillion-dollar commissions as “orchids,” flashy monuments to vanity, believing instead that architecture had a deeper mission as the art and science of giving physical shape to human habitation and to cohabitation. Like many desert gurus and high priests, his philosophy flirted with mysticism, some would argue a New-Age tinge. He believed for instance in the “noosphere,” the idea of an all-encompassing planetary consciousness, a superior collective cognition capable of seeing humanity through to a new transcendence. Ultimately he believed in mankind’s destiny in space: “We can’t limit the presence of life to this tiny corner of the universe. If we truly value it, it is our duty to try and export it.” Envisioning space colonies and orbiting arcologies put him, some would say, in the “moonbeam” camp, and he did in fact have a long relationship with Jerry Brown, who often interviewed him on his radio show We The People. But beyond the esoterica, his formula for cohabitation made some fundamental sense, and elements of it have since become the inspiring principle of New Urbanism. Cities, he would say, need to go back to being “the locales where work, knowledge and conviviality converge and coalesce into a living culture.” And in that sense there is a little Soleri in every mixed-use development currently cropping up, right here in “gigantic” LA. A pioneer in many areas, including the “crowd-funding” to finance his project, he was above all a builder of cathedrals in the desert, much like Simon Rodia or, say, Michael Heizer. But Soleri was no conceptual artist. His impossible grandeur was real, as concrete as the cement he amended with native sands to infuse Arcosanti’s buildings with the natural colors of the desert. A city-in-progress where he cultivated generations of drifters, students and dreamers that made the trek to Agua Fria, where—even if you didn’t find the future of cities—you just might find yourself waking up at dawn in the Sky Suite overlooking the central basilica, and it was one helluva view.