If there is anybody more unpopular in Mexico at the moment than President Enrique Peña Nieto, it is, of course, Donald J. Trump. After a long list of aggressions, rudeness and even “jokes” by Trump, and in the middle of a big domestic crisis—both political and economic, rooted in corruption of Mexican government, but aggravated by the imminent breakdown of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)—Mexicans already have enough reasons to shout.

“Fuck The Wall” is the title of an exhibition in Guadalajara, the country’s second biggest city, in the western state of Jalisco. Famous for its mariachis—the town of Tequila is less than an hour from the city—and its clusters of electronic enterprises, but also for its international book fair, its film festival and its huge community of college students, this regional capital is also a stop for poor migrants from Southern Mexico and Central America on their way to the North, and has a tradition of talented craftsmen and artists. Although this group of Mexican painters are far away from the border, they wanted to make a statement through a personal but also collective and—why not say it—joyful exercise.

“Nobody [from the Mexican government] had expressed a political stance. So, we decided to do it,” says Mauricio Magaña, the owner of 21st Century Art Factory’s gallery, site of the exhibition. Magaña, 45, is a crafts exporter who defines himself as “a frustrated painter.” Probably because of that and the need for more space for his art collection, he decided to open a modest and slightly improvised gallery that is in fact a workshop. Inside this warehouse, located in the Ciudad Granja neighborhood, close to Chivas soccer stadium, 20 men and women—brought together by Magaña and artist Pak Frank—were hurriedly working for two weeks in January to finish the artworks in time for Trump’s inauguration.

“The construction of this wall drives us back to medieval times of walled cities, and it is unacceptable to think that a 21st-century society such as ours can remain as a spectator in front of this decision,” proclaims the wall text of the show. Next to it hangs a depiction of Mickey Mouse’s four-fingered hand with its white glove offering an obscene signal: “Mexico salutes Donald Trump”.

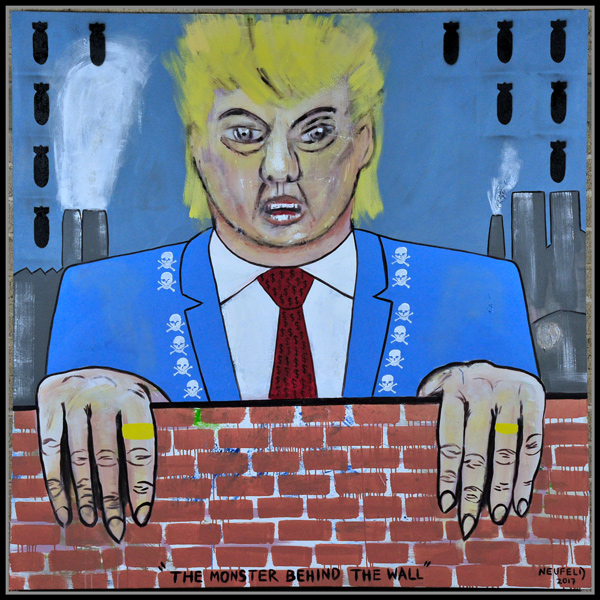

“It’s not only Trump, but the political, economic and army system,” says Daniel Neufeld, 44, whose painting The Monster Behind the Wall, a mixed technique on canvas that portrays a towering orange Trump leaning over the wall with bombs cascading in the background. Born in Guadalajara, Neufeld studied communication before he started painting. A few years ago, he and some peers—feeling “amputated” from mainstream but united by alcohol and parties—founded the collective Gangrena (Gangrene), with the manifesto: “Gangrena members want to rot away the beauty of ‘decorative’ art, of ‘easy’ art, of ‘indulgent’ art,” and aim to encourage non-elitist work.

Daniel Neufeld / The Monster Behind the Wall, mixed technique on canvas, 2017

Despite the main topic of the show, he recognizes that: “I can criticize the gringo, but it’s more urgent that we Mexicans criticize ourselves.” For Neufeld the Trump issues served to distract Mexican people from the country’s major issues. Since the beginning of the year, besides the violence caused by the so-called Mexican War on Drugs, dating back to Felipe Calderón’s presidency (2006–12), people are complaining across the entire nation about the increase of gasoline prices, known as gasolinazo. But back to Trump’s wall issue, he adds, “I don’t know if it’s a science-fiction story or a fantasy, because of what it implies materially.” That’s probably why Neufeld painted those video game–type bombings.

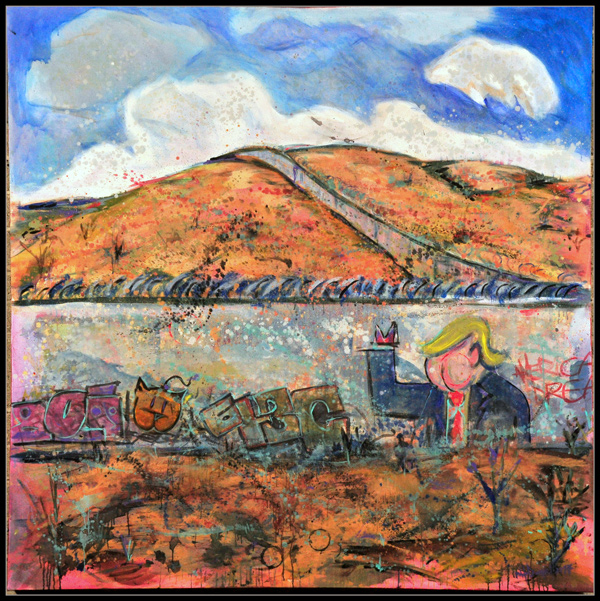

Pablo Arteaga, El rostro de la ignorancia, acrylic on canvas, 2017

Pablo Arteaga, 31, is an admirer of classic landscape Mexican painters José María Velasco (1840–1912) and Dr. Atl (1875–1964), and their understanding of nature; he is also a rock musician. The Anemic Apes and Los rucos de la terraza (Old Men of the Balcony) are the names of his bands. In his artwork, he imagines a desert landscape with a wall. A delicate, almost invisible, character is painting a mural on it with the figure of the U.S. President.

“I thought about the subject of nature [when painting this work],” Arteaga tells me. “Human frontiers are very absurd to me. Trying to break the harmony of the landscape by the means of a wall is nonsense,” he says.

Mauricio Cárdenas, another participating artist, didn’t want to include Trump or the wall in his painting. “I preferred to depict the most dangerous, which is not Trump but the people who follow him.” He adds, “They are the wall.” Make America White Again, his piece, shows a crowd of happy Trump supporters, enclosed by a fence.

“U.S. citizens have the sovereign right to do whatever they want. If they voted for him, what can we do? But another thing is this demeaning attitude toward us, throwing away our relationship as allies. This is something I’ve never known before.”

“I wanted people from the U.S. to know that we Mexicans feel offended as neighbors. We don’t think this is a correct way to solve our disagreements. We share blood, oceans, nature, everything. Like it or not, we have to live together.”

Cárdenas, 40, an architecture school graduate, tells us he finished his artwork in one night, “I forced myself to do it this way. I didn’t feel this painting merited preciousness.” Based on thick strokes, bright colors and even some drippings, it resembles the work of some American classic cartoonists, like the Mad magazine comic strips.

Pak Frank, National Anthem, acrylic on canvas, 2017

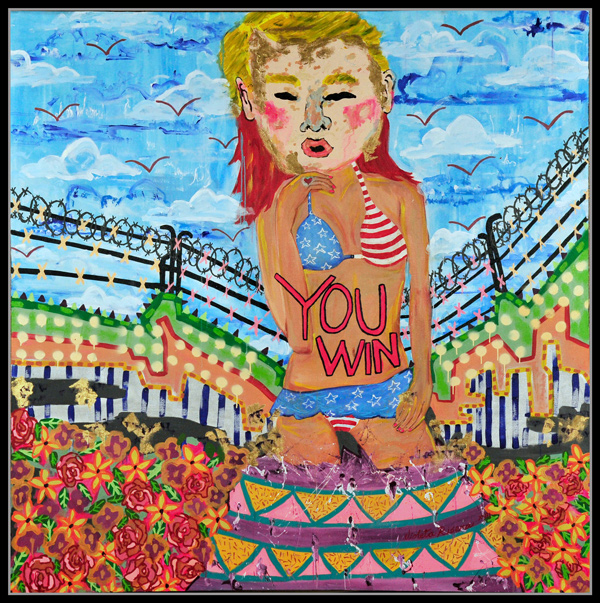

“I don’t feel scared,” about the wall, says artist Pak Frank, 31. “People will find out a way of trespassing it and cover it with art.” Violeta Rivera, 37, an artist from Chihuahua but based in Guadalajara, had been painting a mural recently on the existent wall in Agua Prieta, Sonora, over the border from Douglas, Arizona, about some camel-men. “I portrayed these distorted characters carrying their belongings inside their bodies,” says the painter of You win, another piece in this show.

Pulse, Mi barrio me respalda, mixed technique on canvas

“They can look at us strangely. But we are aferrados (stubborn). We know that we’re going to get ahead”, says Pulse, 33, a former graffiti artist who teaches art in a Guadalajara high school. His painting Mi barrio me respalda (My neighborhood supports me) presents, in a naïve and street style, a bunch of Mexican characters and symbols, including a kind of Quetzalcóatl snake, and even words of a Control Machete song, encircling a blurred, enormous and fluorescent Trump head.

The gallery owner and his team want this show to be itinerant, hoping to find a final destination in the U.S. “Maybe some Democrat will be interested,” says Magaña.

SEE MORE PAINTINGS IN EXHIBITION HERE:

-

Violeta Rivera / You win, mixed technique on canvas, 2017

-

Daniel Neufeld / The Monster Behind the Wall, mixed technique on canvas, 2017

-

Sergio Domínguez “El Jagger,” Premonición combustible, mixed technique on canvas, 2017

-

Tehuti Cortez, El billete, oil on canvas, 2017

-

Mauricio Cárdenas, Make America White Again, acrylic on canvas, 2017

-

Pablo Arteaga, El rostro de la ignorancia, acrylic on canvas, 2017

-

Manuel Rodríguez, Sin título, mixed technique on canvas, 2017

-

Sadek Reynolds, La bandera del tío Sam, mixed technique on canvas, 2017

-

Pulse, Mi barrio me respalda, mixed technique on canvas

-

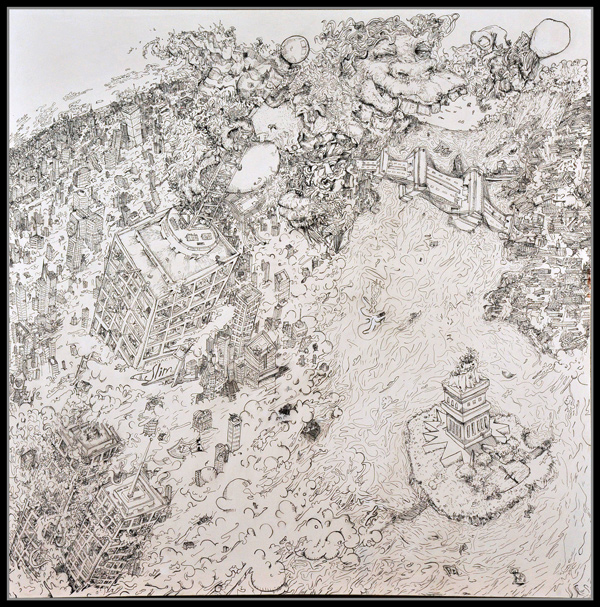

Pit, La gran manzana, ink on canvas, 2017

-

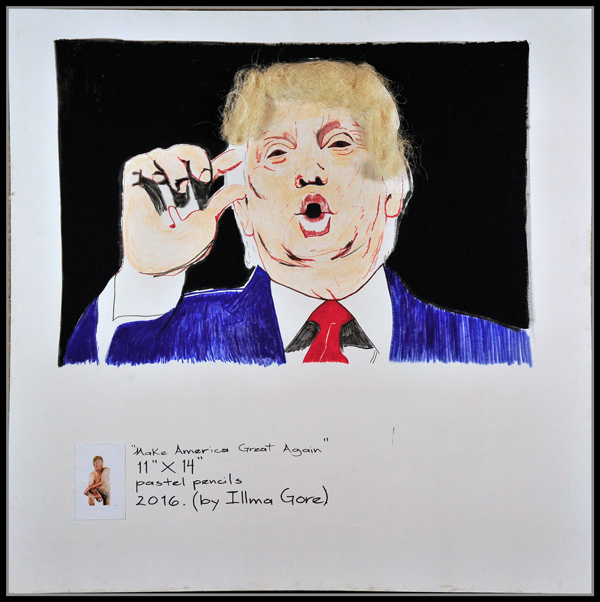

Mevna, Make America Great Again, mixed technique on canvas, 2017

-

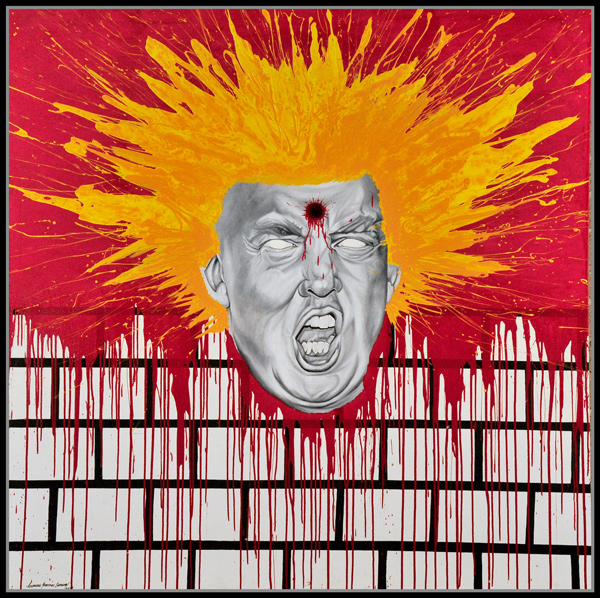

Alex Martínez, Bullet in the head, oil on canvas, 2017

-

Gustavo Islas, La nave de los locos, mixed technique on canvas, 2017

-

Manuel Guardado, Don Trumpas, acrylic on canvas, 2017

-

M. Galindo, El beso de Judas, mixed technique on canvas, 2017

-

Pak Frank, National Anthem, acrylic on canvas, 2017

-

Feng, El dólar es una mentira, mixed technique on canvas, 2017

-

Dyeto, Fuck Trump, mixed technique on canvas, 2017

-

Dyer, El muro de las lamentaciones, mixed technique on canvas, 2017

All photos by Jorge Sevilla.