When an extraordinary windstorm on November 30, 2011 in the San Gabriel Valley decimated the Los Angeles County Arboretum and Botanic Garden, artists helped replenish its 235 felled trees by auctioning works they created from them. Box Collective, a group of woodworkers with individual shops who share resources and exhibit together to promote local and sustainable practices, air-dried the leftover and other windfallen logs for over a year to create the bulk of their pieces for “Windfall” at the Craft and Folk Art Museum.

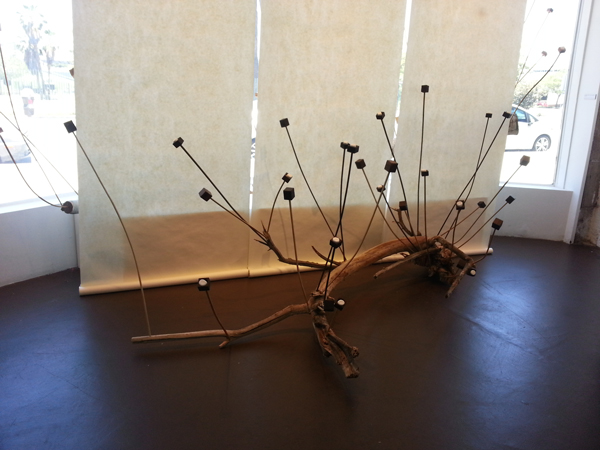

Andrew Riiska, Marshmallow Box Garden

Andrew Riiska’s Marshmallow Box Garden sculptures at the museum’s entrance highlight the show’s theme of new ideas springing from salvaged wood by way of thrifty ingenuity. Steam-bent stems from ash trees felled at the Arboretum bear small lidded box buds made of oak dunnage from a freight train. The stems take new root in an aspen log and an ironwood log downed in different windstorms. The carefully varying sameness of each grain-matched box and arcing stem suggests an artisanal assembly line, a winking oxymoron punch-lined by marshmallows, or oddly edible fictions.

Casey Dzierlenga’s Lorca Table

On the second floor, Casey Dzierlenga’s Lorca Table harnesses a less cheeky contrast. Two clean, warm glints of brass counterbalance a fissured, cool circle of salvaged maple, referencing classicism and a more corporeal religious rite. Dzierlenga fashioned the legs after milk vessels in a Dutch painting, as a study of how light dances along subtle curves. Poet Federico Garcia Lorca, the table’s namesake, favored the soul’s gestalt instincts over the intellect’s analyses, and the grounding intimacy of the table does exceed the sum of its references, conjuring an earthy mysticism.

William Stranger, I Table

Also inspired by contrast and poetry, William Stranger discovered his I Table by resting a slab of paulownia from the Arboretum on a steel I-beam leftover from a contractor’s job. Hand-inscribed on the table’s edge is poet Haruki Murakami’s adage, “The wind knows everything that’s inside you,” and through applying by hand a traditional Japanese burned finish, and polish and wax, Stranger coaxed the wood’s iridescent figure, or two-dimensional texture, out onto its face.

Stephan Roggenbuck’s Love Seat

Repurposing was likewise central to the design of Stephan Roggenbuck’s Love Seat, which was inspired by a bench he had created for a client out of her marital bed frame following her divorce. Supporting the live edge slabs of Lebanese cypress salvaged from the Arboretum is a strong walnut frame, connected from top to bottom by curved pieces, each made of eight thinly milled strips.

Harold Greene, Chaise Lounge

Harold Greene also laminated thin strips on a bowed form to create his Chaise Lounge out of Cedar of Lebanon salvaged from the Arboretum. Slotted to vent air and moisture and recalling the ease of an inverted hammock, it promises and embodies a breezy and elegant poolside stretch.

Robert Apodaca, Blackout Bowls

A CNC, or computerized, mill helped Robert Apodaca carve the tops and feet of his Blackout Bowls, which he completed by hand through scraping and sanding. Preserving the eucalyptus tree’s natural edges, he used a blowtorch to create their blackened finish as an homage to the dark night caused by the same tree toppling power lines near his home in Chinatown in the 2011 storm. The idea for bowls arose naturally when Apodaca observed city crew bucking the tree into short segments for disposal, and he salvaged as many as his truck could hold.

Red Yellow Blue Wood by Cliff Spencer

Eschewing cumbersome CNC programming for the myriad shapes of Red Yellow Blue Wood, Cliff Spencer, with some assistance, patterned and cut them by hand into paulownia from the Arboretum. Several coats of water-based color were sealed under a water-based lacquer, both less toxic than oil-based finishes, and all painstakingly applied by hand.

David Johnson, Media Console

Careful patterning is also evident in David Johnson’s Media Console, afforded this time by properties inherent to a pink cedar tree salvaged from the Arboretum. His use of the entire bottom of the trunk allowed him to bookmatch the milled boards, yielding unbroken stripes of sapwood (found close to a tree’s bark) around the console. He wove cane onto the front and back by hand, and created small cleats on which the shelves rest from carob branches he spotted on a sidewalk in Pasadena.

Samuel Moyer, Arrow Console

Samuel Moyer’s Arrow Console also capitalizes on grain matching, resulting here from splitting lengths from a slender ironwood trunk by hand to preserve maximum grain continuity and the strength of each section. As the blade in hand-splitting follows the grain, Moyer was able to leave raw sinews of wood exposed against his lathe-turned spindles. Selecting which natural wood imperfections to retain is a clear source of joy and challenge in Moyer’s and the other designers’ processes.

RH Lee and JD Sassaman, End Tables

When a claro walnut slab from a windfallen tree in Santa Rosa split in two while drying, RH Lee and JD Sassaman decided to fashion two tables out of the imperfection. A hike along the Sierra Nevada across a sweeping granite and hexagonal basalt landscape culminating at a site where wind had toppled scores of old growth trees inspired them to integrate hexagonal granite spires into their tables. The woodworking was completed in Lee’s Los Angeles shop, and 3D printing was used to cast the spires in Sassaman’s San Francisco shop.

Local practice for Box Collective members entails a few hubs outside Southern California, including Birmingham, Alabama (boasting the country’s second largest urban forest) where Spencer has returned to his roots to open shop, and the Hudson Valley in New York where Moyer and Dzierlenga, while married, operate distinct storefronts. While the logistics of building wood furniture are less cumbersome and costly outside Los Angeles, the craftsmanship and time required to produce an original piece make premium pricing of handcrafted furniture unavoidable. Affordability of earth-friendly, locally crafted goods poses a challenge to many who otherwise champion sustainability.

Johnson responds to this challenge in part by providing more affordable repair and restoration services for some pieces designed by others, but as he and all Box Collective designers are committed to creating original pieces, they encourage consumers to shift their view of cost. A table quickly made in a factory may be cheap, but will likely need to be replaced multiple times and have little meaning to the owner. An original handcrafted table, fashioned from source to finish in concert with the owner’s intentions, is an heirloom or collectible piece designed to hold meaning for generations.

Opting for locally built furniture also allows direct inquiry into all aspects of its production, including the relative toxicity of finishes used and the wood’s origins. Box Collective members routinely use finishes, such as tung oil, relatively low in toxic volatile organic compounds, and acquire logs from forests certified as sustainably managed by the Forest Stewardship Council. Transparency of process finds its most accessible expression in the upshot of this show: Source material is hidden in plain sight. That is, branches we mindlessly sidestep on sidewalks and windfallen logs we might view as traffic obstructions can, when fertilized by intent and imagination, be transformed from inconvenient clutter into functional, durable, meaningful, and beautiful works of art.

Windfall by Box Collective

runs through Sept 4, 2016

Craft and Folk Art Museum

5814 Wilshire Blvd, Los Angeles, CA 90036

www.cafam.org