Self-portraits have been around forever and photos have been around longer than anyone now living. But selfies, I am going to argue, are their own thing. New in important ways.

Definition: on a Venn diagram selfies are a small circle within “self-portraits” and overlapping with—but not identical to—”snapshots with the self in them.” Selfies have to:

1) Be photographs.

2) Include the photographer as a subject.

3) Be on the Internet or otherwise shared socially.

4) Be created with the conscious or unconscious 21st-century assumption that all images are potentially public.

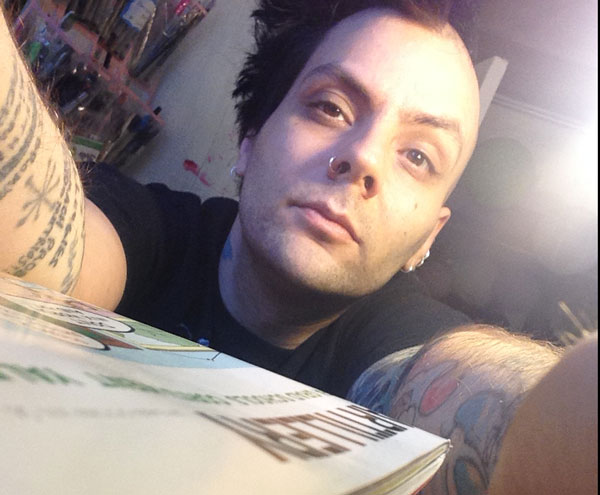

Formally and technically, selfies have mere tendencies—a cluster of characteristics indicating a family relationship, like: a pronounced torqued and non orthogonal relationship of figure-to-ground, by which I mean the wall’s all tilty behind your head; the frequent incorporation of the camera or the arm holding it as a compositional device; the direct gaze or (riskier) the theatrically averted gaze. These tropes and tics are more common in selfies because of current selfie-enabling tech but are not categorically different from what could happen in the traditional post-snapshot late 20th-century self-portrait.

In terms of purpose, however—and therefore meaning—the selfie is a unique form.

The selfie incorporates as assumed content an allied audience—which the traditional self-portrait pretends it can do without and which the old snapshot (stuck in a real physical album somewhere) never had to consider. The selfie’s assumed content is “I want you to look at my head,” its secondary content is narrowing “you” down to an ideal audience.

This is unusual in a public image: The commercial fashion photo industry goes to great lengths to produce an image of exclusivity but in reality the manufacturers lose nothing and gain a great deal when everyone wants to—and can—relate to the images. This is also true of every other kind of commercially-traded photo, including the fine-art photo: they don’t mind appearing to be giving a secret handshake, but they make money by giving it to as many people as possible.

Fashion on the street, however, is not about the illusion of exclusivity, it is about genuine exclusivity. Women (in particular) actually need and use their appearances to tell unworthy, unwanted, or simply incompatible swathes of the public to fuck off, or at least to weigh their behavior carefully in terms of their proximity to a woman’s style target audience: I am this sophisticated, this athletic, this eager to meet new people, this serious. The selfie is far more allied to this individual use of fashion and style than to the fashion photo.

Most images in public announce “Only cool people get this (yes that includes you).” Selfies go “Please do not bother me unless you get this.”

The commercial selfie of the million-follower Instagram celebrity is a weird hybrid because it has to strip away the natural exclusionary layer of personality, but not so much that it becomes forgettable, like all advertising. The image defines a more complicated relationship to audience than the fashion models’—everyone should be hearting at me, but not everyone should be word-bubbling me.

Your garden variety 1995 Kodak photo didn’t expect all this attention, and so does not seek to work as hard to deflect it with style. If photos now tend to look more self-conscious than photos then, this is why.

Selfies reveal personal style for what it always was: not people trying and failing to look like models, not people trying and failing to be themselves, but people consciously taking on a far more complex semiotic environment than models in photos have to. You need the boss to think this, the client to think that, the guy at the next desk to think another thing, the girl at the bar to think a fourth thing altogether. When we joke about looking homeless at the supermarket or like a terrorist at airport security, we’re reporting on omissions and glitches in this complex system.

So: The selfie is not a genre trying to be something else It has its own imperatives and feeds them better than what it might at first appear to be trying to imitate.

Artists have a weird relationship to selfies, now that an ordinary social life all but demands them. If a selfie isn’t their “work” it’s still then part of their image as an artist—and image is everything (everything commercial anyway). Established artists get around this by having an Annie Liebovitz photo of themselves, but emerging artists don’t have that luxury.

If there’s vanity required to take a selfie, it’s only in the way greed is required to accept a paycheck—we no longer have a choice about being seen, we might as well make having a say in how we’re being seen become an ordinary thing. The normalization of the selfie, with its fake and real candor—is a real gain in the war of individuals against a future where everyone is a celebrity and kind of sucks at it.